Agriculture remains a major contributor to the GDP of developing countries. The 20th century saw a rise in agricultural production due to the use of chemical fertilizers, insecticides, and pesticides, better irrigation, and improved breeding technologies. However, this advancement came at the cost of environmental pollution and biodiversity losses. As such, although agriculture is considered a green industry, it is, in fact, the largest sector in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

Global agriculture contributes 25% of the greenhouse emissions, in the form of methane from paddy fields/livestock exhalation and nitrous oxide from cropland soil, which are more potent than carbon dioxide emissions in terms of causing global warming. Agriculture also consumes a lot of water and energy, putting a strain on the limited resources available on earth.

On the contrary, the ever-increasing population and rapidly rising demand for meat require increased production of food, including feed. Therefore, today's agriculture must be both productive and sustainable and this is the area of research that Prof. Ninomiya of the Faculty of Agriculture in the University of Tokyo focuses on. His motivation to make the current weather-dependent agriculture more resilient and efficient in the face of frequent droughts and floods is inspired by a concern that if agriculture is not made sustainable now, in 20-30 years the world may face a shortage of food owing to escalating climate change.

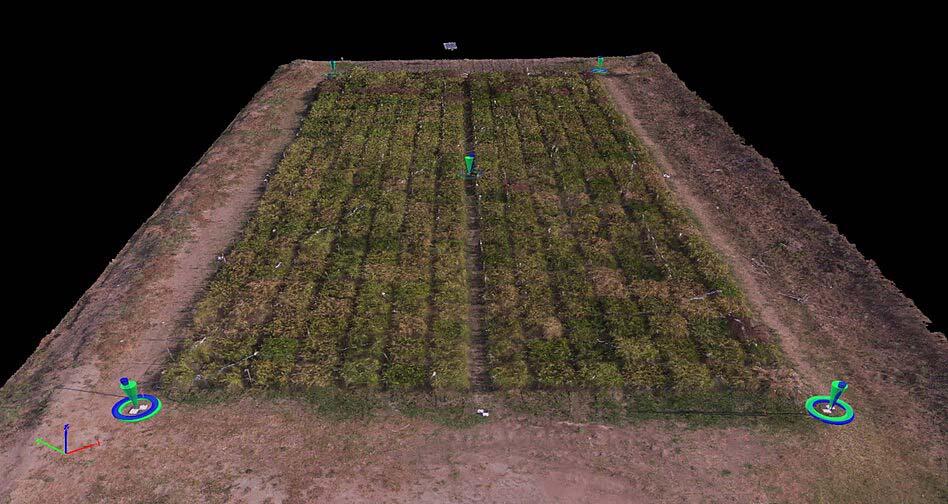

Provided by Prof. Ninomiya

To alleviate the environmental impact of agriculture, Prof. Ninomiya believes in nurturing and training experts, or future "doctors of the earth" or "One Earth Guardians" as they call themselves, in the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, University of Tokyo, which is unofficially called "One Earthology." Remembering Japan in 1970s, Prof. Ninomiya reminisces, "It was not a time when we were hungry, and we didn't have any trouble with food at all. However, I learned during my youthful wanderings around the world that this was not the case in other parts of the world. Even now, food problems are piling up." To deliver enough such rich and healthy food throughout the world, but responsibly, he has concentrated his efforts in developing the agricultural sector in Japan and the world.

The India Connection:

In this journey on the path to sustainability, Prof. Ninomiya has partnered with scientists in India. His first collaboration with the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay (IITB) was because of a chance meeting in an international conference. He had been researching the application of information technology, such as internet-of-things (IoT), big data, artificial intelligence (AI) etc., in agriculture and IITB provided him with a suitable environment to carry on the study further. In 2008, Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) announced bilateral projects with India. Prof. Ninomiya, during his time with the National Agriculture Research Institute of Japan, worked on a joint research project with IITB and established a bilateral research base with India for an ongoing project under the Strategic International Research Cooperative Program (SICORP).

Provided by Prof. Ninomiya

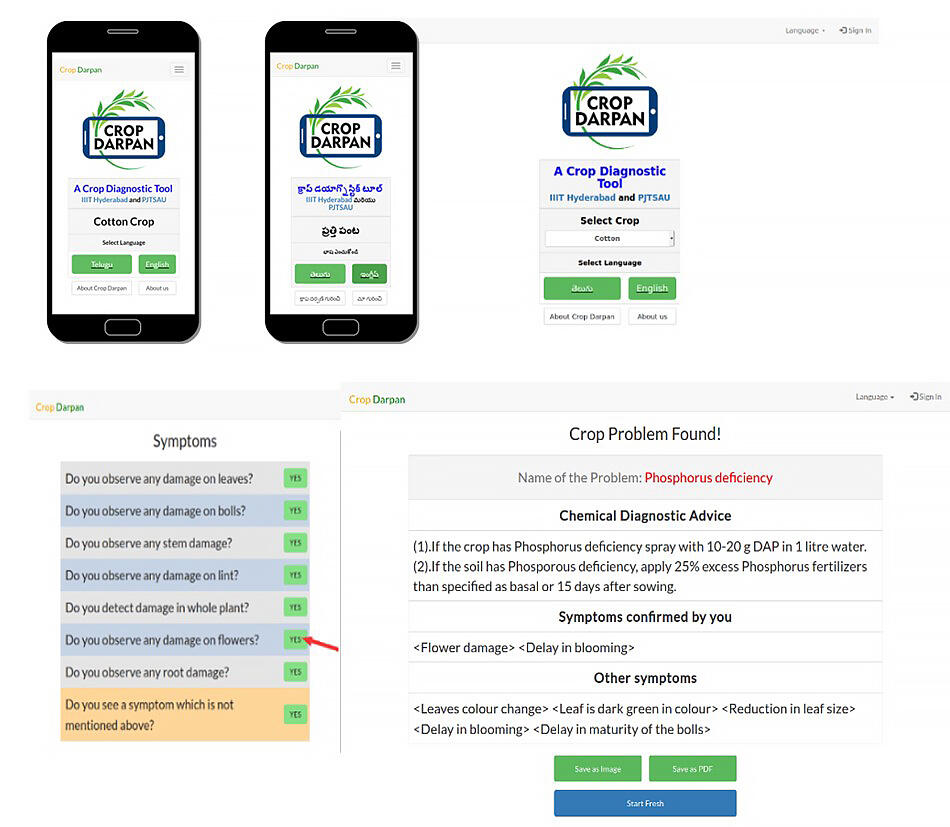

From there he went to Hyderabad and carried on fieldwork there, forging new partnerships with the Indian Institute of Technology, Hyderabad (IITH) and with Professor Jayashankar of Telangana State Agricultural University (PJTSAU). Students were involved from both countries and the relationship extended. Owing to a strong IT sector in India, it turned out to be a good partner for their research. "It's a very special country, and I personally feel that there are many aspects of it that Japanese people get stuck in," recalls Prof. Ninomiya.

As part of the ongoing project with India, Prof. Ninomiya has been working on various crops to make them more climate resistant. Rice is a staple food in India and finds itself integrated in local cultural habits. "Indian researchers in Japan go to the trouble of importing special long-grain rice from India, saying things like, 'rice available in Japan is not good for biryani'," quips a bemused Prof. Ninomiya. The production of rice in India depends on the amount of rainfall received in the monsoons and the level of groundwater replenished. The rice fields in India are not as well irrigated as in Japan--while it is almost 100% in Japan, in India, only about 30% of the rice fields are irrigated. As climate change increasingly begins to show its impact on the environment, he and his colleagues across Japan and India have been working to develop new varieties of rice that will require much less water for cultivation. "In the midst of climate change, it is quite impossible to take 10 years to grow rice slowly. We want to speed up the process as much as possible," explains Prof. Ninomiya. Thus, his current research is geared at harnessing the power of IT to speed up the breeding of rice from 10 years to at least half that speed.

Prof. Ninomiya also observes the lack of proper farmer education in India. For instance, overwatering of corn fields is a common problem that puts an unnecessary strain on the groundwater level. To solve this issue, his team has been working to develop IoT-based soil moisture sensors. "What we are trying to do is to create a system that can provide information on how much water is enough when it is needed, so that we can save water through an app." India is being tried out as a base to develop and disseminate smart agriculture technology for small-scale farmers, who make up about 70% of the world's farmers.

Provided by Prof. Ninomiya

In terms of IT, Prof. Ninomiya speaks highly of India. He believes there's much to learn from Indian researchers in programming and mathematical logic development. He recalls an incident where a Professor in India straightened a messy bundle of Wi-Fi wires at a single go. "He untied the messy strings in one shot. I don't think there is anyone in Japan who can do that," he remarks with remembered admiration. He believes India will contribute immensely to the field of IT research and AI. "I have high expectations that they [India] will become a major hub for the spread of IT agriculture to developing countries around the world," surmises Prof. Ninomiya.

However, when it comes to combining IT with agriculture, Prof. Ninomiya believes that Japan would be far ahead of India. "We have an overwhelming amount of experience and knowledge, and we were able to take a huge lead in that regard, this time in terms of our own." More and more papers on agriculture and plant science are being published. This is where Japan can contribute to the development of Indian research immensely, helping to hone its IT sector to boost its lagging agricultural sector.

Provided by Prof. Ninomiya

Message in the Times of Pandemic:

The Covid-19 pandemic has created challenges for field researchers such as Prof. Ninomiya as they haven't been able to travel to India. However, research efforts have not stopped and are being redirected through the development of skills such as teaching and developing programs while remotely viewing desktops and even building fields in Japan to simulate results and pass on the information to colleagues in India. One silver lining is that now people participate in conferences in huge numbers as they are held online at low costs. He particularly encourages young people to use this opportunity to proactively meet new people and expand their network, which is essential in a research field. "It's important to have a slightly bigger dream and think about what you want to do," emphasizes Prof. Ninomiya, as his message to the youth.

Produced by the Science Japan Editorial Team