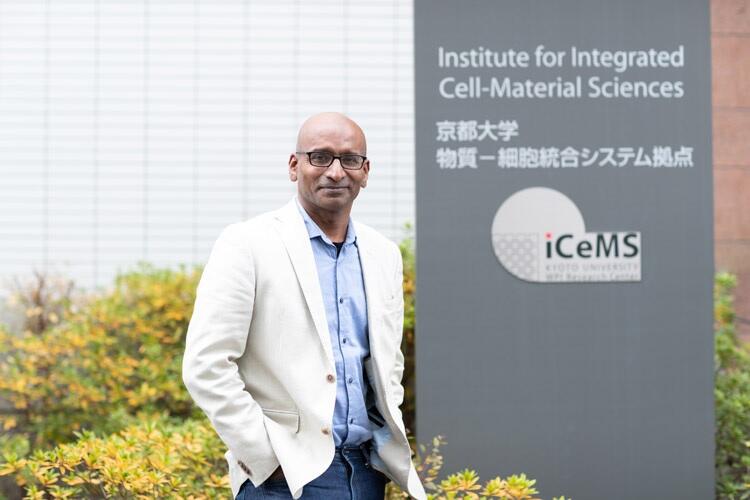

In this edition of the special feature, "Researchers from across the sea," we introduce Easan Sivaniah, a professor at Kyoto University's Institute for Integrated Cell‐Material Science (iCeMS). After being raised in the UK and pursuing a career at distinguished universities, Sivaniah came to Kyoto, the ancient capital of Japan, where he decided that his aim as a researcher was to seek solutions for environmental and energy problems. Never afraid of failure, he is always jumping into new environments and continues adopting a risk‐taking approach in his research. He is also launching a venture company in parallel, with the aim of bringing the technology he developed into the marketplace.

A young man lacking direction

"Actually, I preferred art to science," admitted Sivaniah, when recalling his boyhood. His homeland is Nottingham, England. His parents were immigrants from Sri Lanka and were not wealthy. "I thought I needed to do something that made money, not art. Accordingly, I went into science," explained Sivaniah.

He was a diligent student and eventually joined the Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Imperial College London, one of the most prestigious engineering schools in the UK. After graduating, he went on to the University of Cambridge, another prestigious university, where he earned his Ph.D. His path as a researcher was uncomplicated, but as a young scientist, he was unsure what it meant to conduct research. "Compared to art, it was easier to get some results in the sciences," he said. "But even though I got excellent scores, I didn't see any goals as a researcher. I didn't realize there was something to achieve in my life."

(provided by Sivaniah)

Reflecting on his personal experience, Sivaniah explained, "I would say that most people in their twenties don't know what they want to do. It is, however, important to do the best at what we can do now. If you learn the fundamentals well and gain a variety of experiences, what you acquired until then will be helpful when you find out what you really want to do."

Finding a research direction at 38 after building a career around the world

Sivaniah first came to Japan in 2000, after the end of his tenure as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He chose to conduct his research at Kyoto University because he was drawn to the unknown environment. Sivaniah views it as a world that differs from his previous one because of new possibilities.

Sivaniah, who said he had been blessed with excellent mentors in the UK and the US, also met a professor in Japan who would subsequently guide his research. Professor Takeji Hashimoto was a well‐known specialist in polymer chemistry. Sivaniah recalls, "Professor Hashimoto didn't really force his style on us, even when we were troubled; rather, his policy was 'find your own way.' Having had that experience, I always tried to patiently wait until the younger colleagues in a struggle could arrive at their solutions."

He then pursued his career at the University of Texas and other institutions, and at the age of 38, when he had his own laboratory at the University of Cambridge, he realized what he was meant to do as a researcher. "To that point, it had all been just desk work, and it only furthered my own knowledge," he explained. "So, I decided to apply what I had learned to benefit society, such as seeking a solution for environmental and energy issues."

Sivaniah's idea was to use a membrane made of a polymer compound to separate substances. His explanation was as follows: "Various membranes have numerous pores through which small molecules can be passed, whereas large ones cannot. We thought we could develop a new platform of purifying air and water by using such membranes to remove harmful substances, such as viruses or bacteria."

In 2013, Sivaniah decided to return to Japan. "I had been invited by an Australian university on favorable terms, but I thought I would have a better chance of success in Japan, where I could take advantage of the differences in culture and background, rather than in a setting dominated by researchers from Europe and the United States," explained Sivaniah. Consistently, he faced the challenges inherent in an unknown field.

Naming the laboratory by combining the words "purity" and "curiosity"

Sivaniah remembers that his return to Japan was motivated by introductory information from a senior colleague at the University of Cambridge and the subsequent offer of a tenured associate professorship by Distinguished Professor Susumu Kitagawa, the director of Kyoto University's Institute for Integrated Cell‐Material Science (iCeMS) at the time.

Three years later, Sivaniah became a professor and named his laboratory "Pureosity." The name of the lab was coined by mixing "pure" and "curiosity," and it represented Sivaniah's approach to research. People who agreed with this approach, irrespective of nationality or field, came together as one team to address environmental and energy issues.

In 2017, they announced the development of a new polymer membrane that efficiently separates CO2. This innovative material overcame the technical obstacles in processing speed and accuracy in carbon dioxide separation through the use of membranes. Since then, Pureosity has achieved much, but the team's basic approach has remained unchanged.

Establishing a start‐up company over a seven‐year period

Sivaniah's laboratory is jointly conducting research with OOYOO Co., Ltd., a company that is working on the implementation of the technologies developed by his lab in society. Sivaniah illustrated that the University of Cambridge was very active in creating venture companies, explaining that he chose to pursue entrepreneurship soon after arriving in Japan.

It took seven years to establish OOYOO, but the company has successfully grown, and the number of employees has increased from one to ten in less than three years since its creation.

Its main focus is the separation and recovery of CO2. "With our technology, even small and medium‐sized plants, unable to address the issue on their own, can recover carbon at a reasonable cost." empathized Sivaniah. A joint project with a major chemical manufacturer has already begun, and the company is striving to achieve net‐zero CO2 for a variety of stakeholders.

Expanding technology by having people think it is beautiful

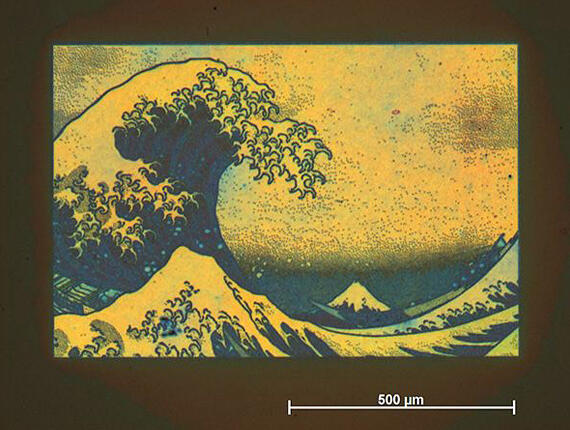

Pureosity is also engaged in developing an ink‐free printing technology. This technology builds upon the reflection of light with a specific color tuned by precisely controlling the size of cracks formed when transparent material is bent. The principle is the same as the brilliance emanating from the body of a chafer or wings of a peacock. This technology platform has the potential to contribute to society in many areas, for example, by allowing direct printing on the surface of plastic bottles—thus avoiding the need for plastic packaging—or by using watermarked banknotes, consequently, preventing the production of counterfeit money.

In 2019, they succeeded in generating all the colors in visible light. Prior to the press release of these achievements, Sivaniah and his team reproduced works by Katsushika Hokusai and Johannes Vermeer. Their objective was to attract the interest of more people. Sivaniah explained, "It was not enough that only geeks appreciated technology; you needed to actually explain it to people who were not geeks. Before our products can be useful, they must first be beautiful," he added.

(provided by Sivaniah)

However, in the process of its development, the picture turned white, even though the intention was to reproduce it in green. Everyone in the lab thought, "This was a failure," but Sivaniah had something else in mind. He stated, "Green color reflects only green light, whereas white color reflects light of the whole visible spectrum." He went on to say, "Applying this method, you could consider its use for heat‐shielding curtains or some such use." Sivaniah is always exploring new possibilities. He believes the knowledge and experience he has accumulated over the years has enabled him to see great potential.

Turning "differences" into "advantages" and facing challenges

Pureosity and OOYOO employ people from various countries and regions in Asia and Europe, roughly half of whom are Japanese. Conversations in the laboratory are a mixture of Japanese and English, and Sivaniah uses both languages as necessary when interacting with different partners. When Sivaniah first arrived in Japan, in 2000, he did not understand Japanese at all.

After his return to Japan in 2013, as a matter of necessity, he needed to speak Japanese to manage his laboratory and negotiate with people outside the lab. He learned to master the language while using it.

Considering his experience, Sivaniah advised, "I think Japanese researchers should also go abroad at a young age." He pointed out that "The most important thing is not to acquire the language, but to have a different experience in a new world." He said, "I believe that if you don't take on challenges such as that, you will always remain unaware of the things you need to do for yourself."

Sivaniah stressed, "It's vitally important to have the attitude of learning more from unplanned encounters than being satisfied with foreseeable successes." Following in the footsteps of his parents who came to the UK from Sri Lanka as immigrants, Sivaniah chose adventurous challenges in the Far East, a long way from the UK. Accordingly, he managed to turn differences into advantages. Sometimes you can search for a clue to new inventions and obtain unexpected results. Venturing out into the uncharted world with curiosity may be a quick path to success.

Having gained experience in various places, as well as finding his own path, Sivaniah is no longer lost. Together with his colleagues around the world, Sivaniah will continue to meet the challenges of developing technologies that will help preserve the global environment.

Profile

SIVANIAH Easan

Professor, Institute for Integrated Cell‐Material Sciences (iCeMS), Kyoto University

B.Sc. in Chemical Engineering from Imperial College London. Obtained a Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge. He was a Research Fellow at the University of California, Santa Barbara, a Research Fellow at Kyoto University, an Assistant Professor at Texas Tech University, a Full‐time Lecturer at the University of Leeds, a Research Group Leader at the University of Cambridge, and an Associate Professor at the Institute for Integrated Cell‐Material Systems, School of Advanced Studies, Kyoto University, before assuming his current position in 2016.

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.