Blood cells such as white and red blood cells made from hematopoietic progenitor cells within the bone marrow decrease in number as a side effect of many anti-cancer drugs, but gradually recover afterwards. Normal treatment involves administering anti-cancer drugs again once the cells have recovered to a certain level. As it takes time for the cells to recover, patients suffer a variety of side effects.

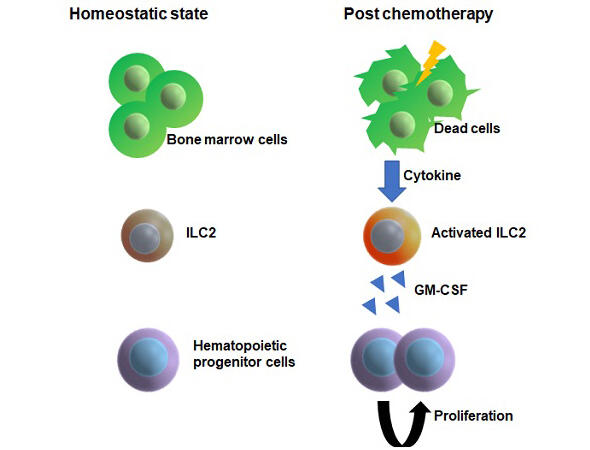

A research group consisting of Assistant Professor Takao Sudou and Professor Masaru Ishii of the Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University, and their colleagues has, for the first time in the world, clarified that group 2 innate lymphoid cells inside the bone marrow perceive damage to the bone marrow after chemotherapy and secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and thus are connected to hematopoietic recovery. "In principle, innate lymphoid cells are propagated outside of the body and transplanted after treatment, which can alleviate side effects. In addition, if we can develop a drug that stimulates this process, we may be able to use it as an agent to inhibit side effects," says Ishii. The research is published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Many of the anti-cancer drugs currently in use stop the proliferation of cancer cells and destroy them by halting the cell cycle, but this affects other types of cells as well as the cancer, meaning that blood cells are reduced in number. If, for example, white blood cells decrease, it is easy for a patient to contract an infection, and patients will become anemic if their red blood cells decrease. After this, the hematopoietic progenitor cells left in the bone marrow actively divide and attempt to increase blood cell numbers--but the mechanism behind this was poorly understood.

The research group used in-vivo live-imaging technologies that can visualize live cells in living creatures on mice, and found that hematopoietic progenitor cells, which normally move around, stopped moving after anti-cancer drugs were administered. They therefore carried out a comprehensive investigation of the gene expression of the hematopoietic progenitor cells after the anti-cancer drugs were administered, and learned that these are stimulated by GM-CSF and become active. In fact, after GM-CSF knockout mice were administered with anti-cancer drugs, their blood cell count greatly decreased compared to the wild type, and they unfortunately died after around 10 days.

To find out which of cells within the bone marrow created the GM-CSF, the group carried out single-cell RNA analysis; by closely investigating the gene expression of each cell within the bone marrow, they found that group 2 innate lymphoid cells secrete GM-CSF. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells do not normally actively secrete GM-CSF--they detected the death of cells in the bone marrow and increased the expression of GM-CSF.

Thus, by cultivating and propagating group 2 innate lymphoid cells taken from the mice and transplanting them after administering anti-cancer drugs, the group found that the hematopoietic progenitor cells in the bone marrow recovered significantly: around 2.5 times faster when compared to mice only administered with anti-cancer drugs.

Sudou noted, "We've only done this with mice, and we must go through each stage to use it on humans and bring it up to clinical use, but as I am looking at bone-marrow transplant patients in our Department of Hematology, I want to ensure this has clinical applications in the future."

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd.(https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.