A joint research group, consisting of team leader Sa Kan Yoo, trainee Ayaka Sasaki (at the time of the research), technical staff member Tomomi Takano, team leader Takashi Nishimura (at the time of the research), and others from the RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research, has used Drosophila to discover the molecular mechanisms by which intestinal stem cells proliferate excessively and become cancerous as they age. The research was published in the online edition of Nature Metabolism.

As cells age, gene mutations accumulate and the cells undergo oncogenesis (the process of cells becoming cancerous). Almost all cancers are caused by aging, but the molecular mechanisms by which this occurs in the natural circumstances that accompany aging are not clear. This is because it would take too much time using experimental animals such as mice or rats.

Thus, the research group carried out their research using Drosophila melanogaster, in which 62% of human disease-causing genes are present, and which have a short, 2-3 month lifespan. More specifically, the team used three strains of Drosophila wild-type and two strains of white (white eye) mutants, which are often used in almost exactly the same way as wild-types in genetic experiments, and counted cell division in the intestines of the bodies of young Drosophila (one week after emergence) and in old Drosophila (one and a half to two months after emergence). This is because intestinal stem cells undergo oncogenesis when they proliferate excessively. It is thought that if a great deal of cell division can be observed in aging individuals, intestinal stem cells are over-proliferating with age. However, while excess proliferation of intestinal stem cells with age was actually observed in the wild-types, it was not seen in white mutants.

We know that the white gene encodes a type of membrane protein called an ABC transporter. Until now, we were aware that the white gene controls the synthesis of eye pigment and nervous system functions, but we didn't have a good understanding of how this is linked to the metabolic dynamics of the body as a whole.

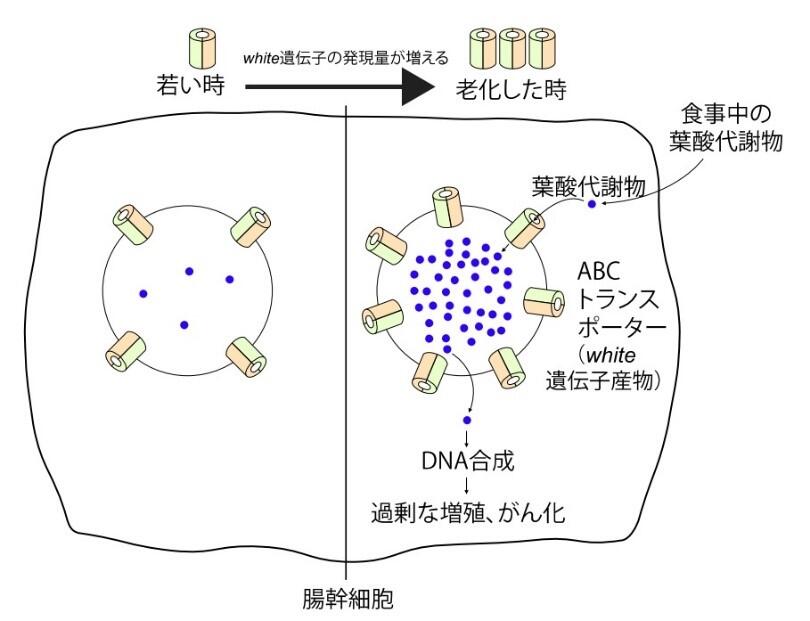

The joint research group carried out metabolite analysis in the young and old members of both the wild-types and the white mutants. As a result, they made a new discovery that tetrahydrofolic acid, a folic acid metabolite, accumulates in the intestinal stem cells of old wild-type Drosophila, but this accumulation does not occur in the white mutants. Tetrahydrofolic acid is a substance that controls DNA synthesis, and is needed for cell proliferation. When the researchers carried out detailed analysis, they found that when an individual ages, firstly there is increased expression of the white gene in intestinal stem cells, and consequently tetrahydrofolic acid accumulates in intestinal stem cells. The team ascertained that the tetrahydrofolic acid that has built up in the cells encourages DNA synthesis, and the cells proliferate and facilitate oncogenesis. Meanwhile, they learned that by artificially inhibiting the expression of the white gene in intestinal stem cells or inhibiting the tetrahydrofolic acid build up, intestinal stem cell oncogenesis was suppressed, and the life span of the Drosophila was extended by around five days. Moreover, if drugs that inhibit DNA synthesis were administered, no visible intestinal stem cell oncogenesis occurred with age.

These outcomes suggest a model that during the aging process of Drosophila, a folic acid metabolite (tetrahydrofolic acid) accumulates in intestinal stem cells due to the workings of a white gene product (ABC transporter), which is increasingly expressed in intestinal stem cells, and DNA synthesis is promoted, causing cells to proliferate excessively.

Team leader Yoo states that, "Homologs of the white gene are also present in humans. Folic acid inhibitors are often used in actual cancer treatments. One thing to note about these results is that we have learned that oncogenesis is promoted by folic acid alone."

Meanwhile, when the white mutant discovered by Morgan in 1910 is genetically modified, the color of its eyes changes from white to yellow, red, or other colors, so it is easy to select individuals in whom gene transfer has been successful, which are used for different types of research. The research group clarified that more than 40 types of metabolite in the white mutant differ from those of a wild-type.

Team leader Yoo points out that, "It doesn't have a significant effect on developmental research, but in physiology or metabolic research it is possible that these differences could lead to incorrect results if researchers do not make comparisons with the wild-type." Although the research group attempted to reproduce an experiment from a paper, there were elements that did not go well, and it is said that the cause was the differences in metabolites. Care must be taken when carrying out research using Drosophila.

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd.(https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.