On July 7, the research group led by Assistant Professor Shinya Aoyama of the Department of Neurobiology & Behavior of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at Nagasaki University (Junior Researcher of the Organization for University Research Initiatives at Waseda University: 2015-2019), Professor Shigenobu Shibata of the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Waseda University, and Lecturer Hyeon-Ki Kim announced their discovery that the time of protein intake influences the muscle mass. Their findings were published in the online July 6 issue of the US open-access journal Cell Reports.

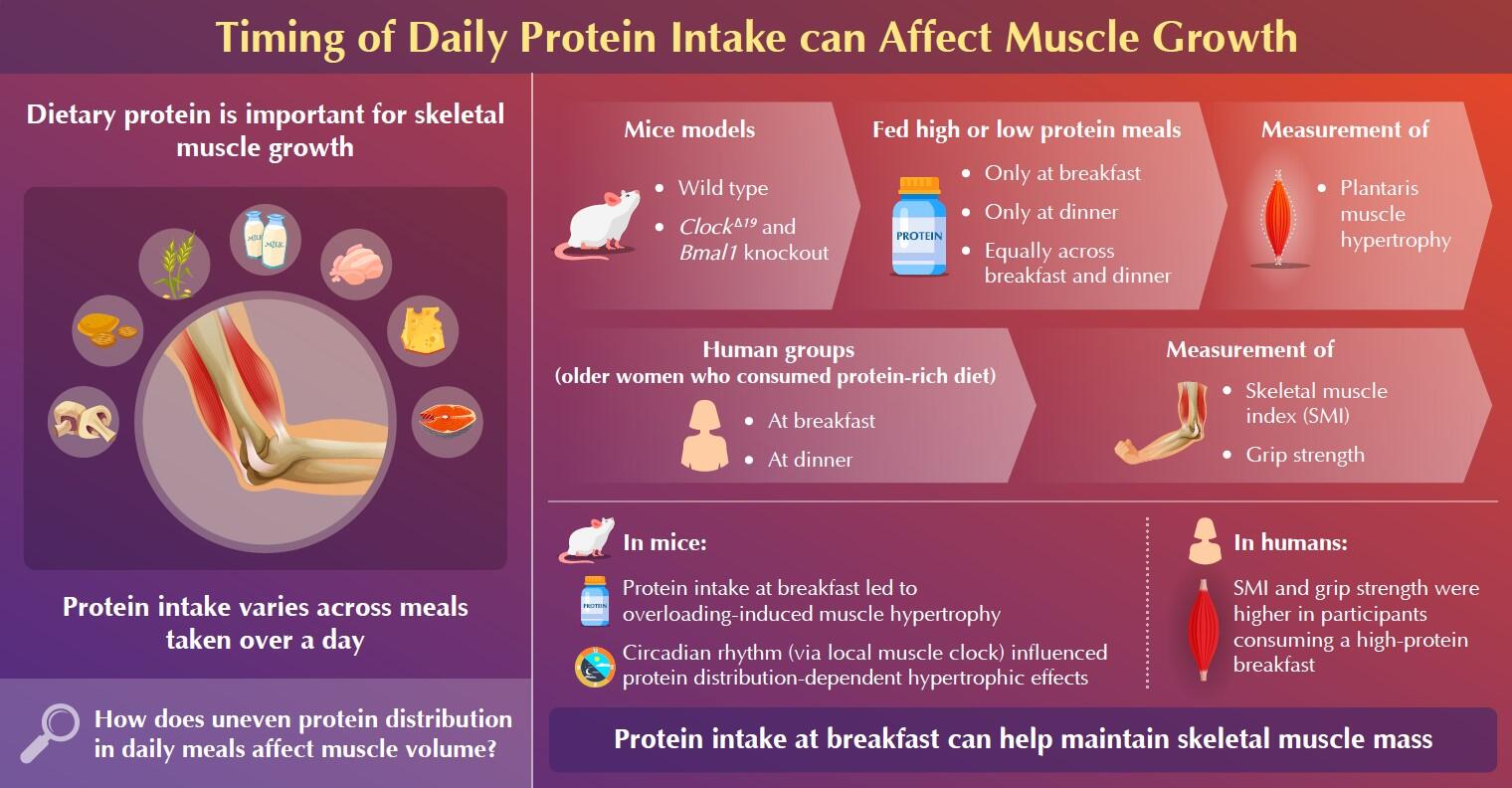

Proteins ingested through the diet are important for the synthesis of skeletal muscle and maintenance/increase of muscle mass. Dietary surveys conducted in different countries have shown that protein intake during breakfast is low in many countries and that the protein intake varies across three meals consumed in the morning, noon, and evening.

Although epidemiological studies have shown that such variations in daily diet are related to skeletal muscle function, whether protein intake being low at night, in addition to in the morning, has an impact is largely unclear.

In this study, the research group revealed that in mice the time of daily protein intake affects muscle mass gain due to overloading-induced muscle hypertrophy. In addition, they focused on the clock genes, which control the biological clock, as key factors responsible for the difference in the time-dependent effect of protein intake to analyze the involvement of the biological clock in the muscle mass-increasing effect of protein intake time. Furthermore, they investigated the relationship between the protein intake in three meals and muscle strength and mass in humans.

The research group fed mice two meals a day to standardize their total amount of daily protein intake. After the change in the protein content of each diet, the muscle mass increase was more prominent in the mice consuming a large amount of protein at breakfast than in those consuming a large protein amount at dinner or those consuming evenly at breakfast and dinner.

In other words, considering the equal amount of daily protein intake, the muscle mass can be more effectively increased when dietary proteins are ingested in the morning (at the early active phase).

(Provided by Waseda University)

They also found that branched-chain amino acids are involved in the increase in the muscle mass related to breakfast protein intake. Using the mice fed two meals a day as described above, they showed that the ingestion of a branched-chain amino acid-supplemented diet is more likely to increase the muscle mass at breakfast than at dinner. Such an effect of ingestion at breakfast was not observed with diets supplemented with other amino acids.

Furthermore, to investigate how the increase in the muscle mass due to the time of protein intake is related to the biological clock, the research group measured protein intake patterns and muscle mass during breakfast and dinner in mice with a mutation in the clock gene Clock and in muscle-specific Bmal1-knockout mice deficient in the clock gene Bmal1. The results showed that the muscle mass-increasing effect of breakfast protein intake was absent in these mice, indicating that the muscle biological clock is involved in the muscle mass-increasing effect depending on the protein intake time.

In a study on humans, the research group investigated the relationship between protein intake of three meals and skeletal muscle function in elderly women. It showed that those who consumed a large amount of protein at breakfast had higher skeletal muscle index and grip strength than those who consumed a large amount of protein at dinner; a positive correlation was observed between the ratio of the amount of breakfast protein intake to the amount of daily protein intake and the skeletal muscle index. As this was an observational study, the causal relationship remains unclear; however, the results suggest that morning protein intake may be effective in maintaining and increasing muscle mass in humans as well.

The research group foresees other questions to tackle and suggested that "it is necessary to evaluate the molecular mechanism by which the clock genes actually produce the time effect of protein intake, as well as the effectiveness of breakfast protein intake by intervention studies in humans. Thus, there are still many gaps to be addressed."

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd.(https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.