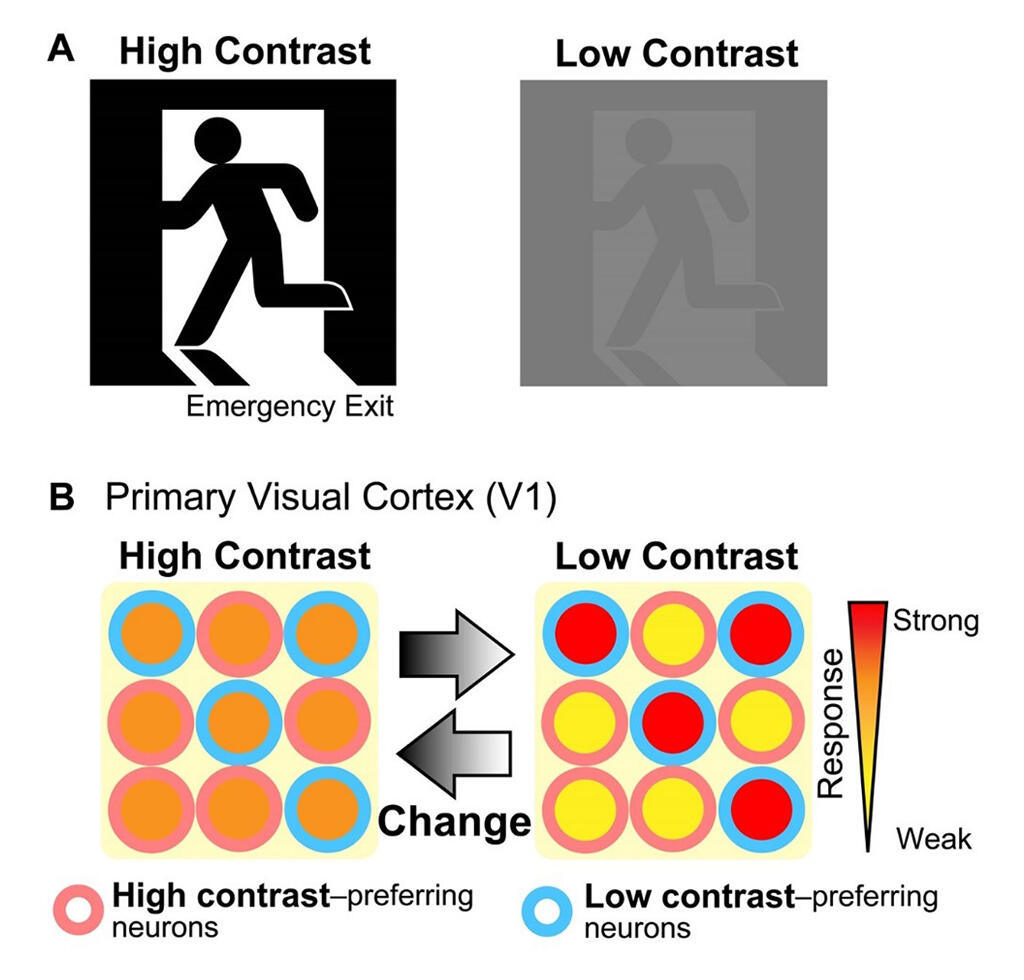

A research group comprising Dr. Rie Kimura, a special assistant professor (currently an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo), and Professor Yumiko Yoshimura, both from the Division of Visual Information Processing, National Institute for Physiological Sciences (NIPS), found that by repeatedly viewing the same image, the number of neurons that responded strongly to blurry and hard-to-see images increased in the primary visual cortex. These cells contributed to the visual perception of the difficult-to-see images. When seen repeatedly, an object can be perceived even if it is slightly blurry and difficult to view. The neurological mechanism that makes this phenomenon possible was previously unknown.

In this study, to reproduce this phenomenon, rats were trained by having them repeatedly perform a task where they had to determine the direction of stripes. They were trained to push the lever when vertical stripes appeared and pull it when horizontal stripes appeared. After the training, the rats could discriminate the stripes even at a lower contrast that made the striped difficult to see.

To clarify the changes that occurred in the brain during this task, the neural activity of the primary visual cortex was recorded using a multipoint electrode. It was found that by learning through the experience of repeatedly viewing the same image, the primary visual cortex of the rats had more cells than normal that responded more strongly to low-contrast, hard-to-see images than to high-contrast, easy-to-see images.

Provided by NIPS

Next, the function of the cells that strongly responded to the low-contrast images was investigated. It was found that these cells had different responses to low-contrast vertical and horizontal stripes, i.e., they distinguished between vertical and horizontal stripes. The cells were also strongly active when the rats could correctly distinguish low-contrast images. The results showed that the cells that responded strongly to low-contrast images contributed to visual perception when images that had been repeatedly viewed became difficult to see.

To clarify the mechanism underlying the strong response to low-contrast images after learning, the group assessed the differences in neural activity before and after learning. The results showed that after learning, in the primary visual cortex, the excitability for both contrast levels strengthened. Further, for high-contrast images, the suppression strengthened simultaneously. These results suggest that the excitation and suppression behaviors of cells were not activated for high-contrast images, but were fully activated for low-contrast images, eliciting a strong response. "This study began in 2014, and we found the presence of strongly active cells for low-contrast images in early stages," said Dr. Kimura. "Subsequently, we continued to investigate the missing data and added them, performing a detailed analysis. In the future, we would like to clarify in further detail how interactions with other brain areas contribute to flexible information expression in the brain using the latest experimental techniques, such as manipulation of the neural activity."

■ The primary visual cortex is the first area of the cerebral cortex to receive visual information.

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd.(https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.