More than half of endangered Japanese juvenile eels survive even after they are preyed on by other fish. This was revealed by Dr. Yunami Hasegawa, a doctoral student at the Graduate School of Fisheries and Environmental Sciences, Nagasaki University (4th year in the Faculty of Fisheries at the time of the experiment), and Associate Professor Yuki Kawabata via collaborative research with Dr. Kazuki Yokouchi, a senior researcher at the Fisheries Research and Education Organization. Their work was published in the journal Ecology of the Ecological Society of America.

The Japanese eel is an important fishery resource; however, its population has decreased significantly and it has been declared as an endangered species. However, no study has directly investigated the predator avoidance behavior of Japanese eels, which is important for the maintenance and recovery of their population. Therefore, from 2020, the research group started research to observe the offense and defense of dark sleeper fish, which are predators that inhabit rivers in large numbers, and Japanese juvenile eels in the same tank.

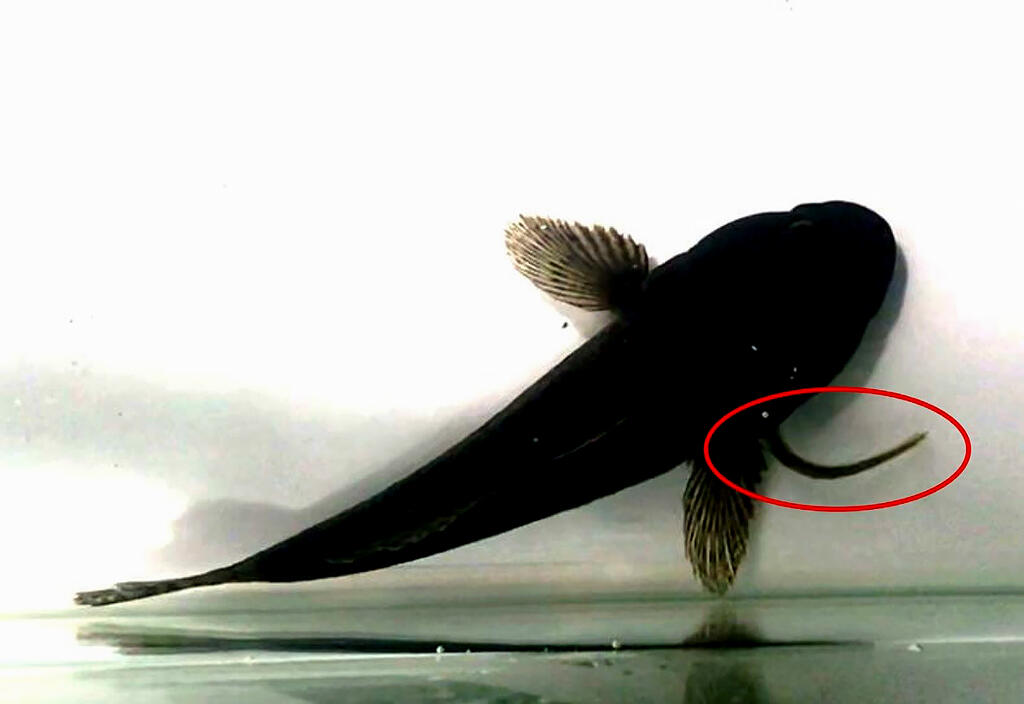

At the beginning of the experiment, a high-speed camera was used to capture the moment when the Japanese eel fends off a predator's attack or gets eaten. However, Mr. Hasegawa, who was in charge of the experiment, discovered that the Japanese eel, which should have been eaten by predators, were swimming in the aquarium. He thought, "It may have come out of the predator's mouth in some way;" therefore, he switched to a normal camera that could shoot for a long time and observed. It was then found that even if Japanese eels were captured by predators, more than half (28 out of 54: 51.9%) escaped via the gaps in the gills.

There are some living organisms that survive after being captured by predators; however, most of these mechanisms are passive, for example, they are excreted via a hard shell without being digested. However, the behavior observed in the Japanese eel this time was that they actively escaped from the gap of the predator's gills, which is a rare behavior, even when considering non-fish taxa, such as invertebrates. In addition, all 28 animals that escaped had escaped tail first. This may have something to do with eels being good at swimming backwards.

This finding may also lead to understanding the evolution of elongation and slithering behavior. The elongated shape of the eel has evolved independently in various families, such as Gobiidae and Siluridae. However, the hypothesis is that the use of narrow gaps and the promotion of digging behavior are the only explanation to the kind of survival and breeding benefits of the body shape.

In the future, the scope of this research will be expanded, and experiments will be conducted to feed predators with elongated eels of various species. This could test the hypothesis that the ability to "escape from a predator's mouth" promoted the evolution of elongated shapes. Currently, these fish are being released nationwide as one of the resource recovery measures for Japanese eel. However, because many large released fish have poor growth and biased sex ratio toward males, small fish are recommended to be released. In general, small individuals have low ability to avoid predators and are often preyed on by predators that inhabit stocking areas. Therefore, it is thought that the results of this research will be useful in considering the kind of eels that should be released for high survival rates and obtain a high release effect.

Provided by Dr. Yunami Hasegawa, Nagasaki University.

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd.(https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.