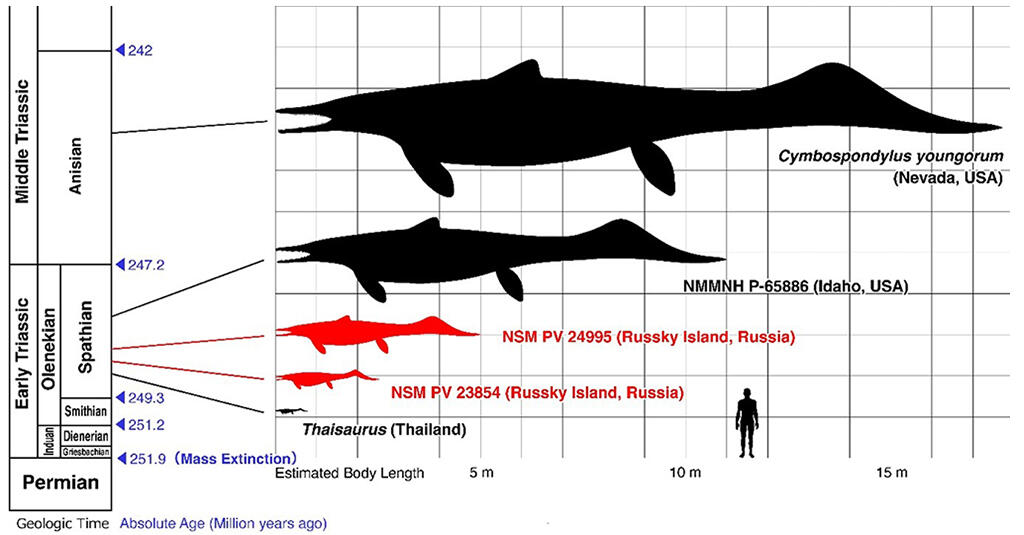

On April 27, a research group consisting of Assistant Professor Yasuhisa Nakajima of the Department of Natural Sciences, Faculty of Science and Engineering, Tokyo City University, Group Leader Yasunari Shigeta of the Department of Geology and Paleontology, National Museum of Nature and Science and their colleagues announced that, together with the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle (Paris), the Russian Academy of Sciences and the University of Bonn (Germany), they have discovered two of the world's oldest basal ichthyopterygian fossils in the strata of Russky Island, south of Vladivostok (Russia). Both fossils were discovered in Spathian substage strata (Early Triassic; approx. 249 million years ago), and the group clarified that one had reached a total length of five meters, the largest of any ichthyopterygian discovered in this period. Fossils of the period in which ichthyopterygians appeared are rare around the world, and it is hoped that this outcome will help to clarify evolution in this early period. The results were published in the April 1 issue of Scientific Reports, an international science journal.

Provided by Tokyo City University

Ichthyopterygia were sea reptiles that appeared in the Early Triassic (around 250 million years ago); they are characterized by their beaks with many teeth, short necks, and four legs that had transformed into flippers, and a tail. Early basal ichthyopterygians had long, thin bodies (appearing to be mid-way between a lizard and a fish), which they undulated left and right to swim in the sea. From the Jurassic Period onwards, they evolved to resemble tuna or marlins. They increased in size during the Middle and Late Triassic, and reigned at the top of the food chain in the ocean's ecosystem, but declined during the Cretaceous Period and are thought to have vanished around 94 million years ago, before the great extinction of the dinosaurs around 66 million years ago.

To date, Ichthyopterygian fossils have been discovered in Mesozoic Era strata around the world, but of these, basal ichthyopterygians from the Early Triassic have only been discovered in a limited area; even in Russia, they had only been reported and their whereabouts were unclear.

A survey team from the National Museum of Nature and Science has been continually surveying Primorye in the Russian Far East to research fossils such as ammonite. In both the 2006 and 2017 surveys, they succeeded in collecting a nodule (a mass of sedimentary rock) from Spathian substage strata (Early Triassic) that contained the bones of vertebrates. These two nodules were discovered in locations a few dozen meters apart, along the same peninsular coastline.

Assistant Professor Nakajima, who is an expert on marine reptiles, carried out a detailed analysis of these by comparing them with previously discovered ichthyopterygian fossils, and more. He found that the first nodule contained two vertebrae around 3 cm in diameter, their processes, ribs, and more. The results of his analysis concluded that this was a basal ichthyopterygian with a body length of around 2.5 meters, based on the large size of the indentations before and after the vertebrae.

The second nodule contained a bone 13.1 cm long. The results of Assistant Professor Nakajima's analysis concluded that this was the humerus of a large basal ichthyopterygian with a body length of five meters, based on its similarity to the humerus of a Cymbospondylus, a large basal ichthyopterygian that lived in the Middle Triassic. This ichthyopterygian was from a slightly more recent time period.

The inner structure of these ichthyopterygian bones was investigated using CT scans and microscopes. This showed that the bone density was exceptionally low compared to other reptiles, and that the bone itself was constructed from light, sponge-like structures, similar to a modern whale. From this, the group learned that these ichthyopterygians had abandoned life on land, and were perfectly adapted to life in the sea, including in distant and deep waters.

Group Leader Shigeta and his colleagues examined the strata from which the two nodules were obtained for ammonite fossils and found it had accumulated around 249 million years ago, 3 million years after the mass extinction event at the end of the Permian Period, the final period of the Paleozoic Era.

Ichthyopterygians appeared in the Triassic Period during the Mesozoic Era and flourished in the sea for 160 million years. From this outcome, it was clear that these fossils were from within the 3 million years at the very start of their history. This shows that ichthyopterygians, which appeared directly after the mass extinction, became perfectly adapted to living in the ocean in a very short time from a geological perspective. They appear to have grown to have a body length of five meters, comparable to a modern great white shark or orca whale, and to have dominated the top of the oceanic ecological pyramid in a short space of time. It is thought that the mass extinction event at the end of the Paleozoic Era caused particularly great harm in the oceans, and it is clear that the destroyed ocean ecosystem rapidly recovered.

Assistant Professor Nakajima commented, 'The importance of the Russian ichthyopterygian fossils has become clear, and we wanted to excavate more, but international circumstances have made this difficult. In the future, we want to promote excavations and surveys of Triassic ichthyopterygian fossils in Japan, which are equally important, especially in Miyagi Prefecture.'

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd.(https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.