In July, a research group consisting of Senior Principal Scientist Tsunashi Kamo of the Division of Agroecosystem Management Research, Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences, National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO), and his colleagues announced that they have worked with Shimane Agricultural Technology Center and the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute to clarify that wild Bombus ardens ardens (bumblebees) are great contributors to the flower pollination of Japanese persimmons around the country. The group's findings come from a survey of insects visiting persimmon flowers, which was carried out in the top 10 prefectures by persimmon production area in Japan.

Provided by NARO

Their research outcomes were reflected in NARO's pollinator survey manual (Japanese), which was published in March this year. It is hoped that these results will lead to low-cost, low labor intensive fruit tree/fruit and vegetable cultivation.

More than 75% of the key crops around the world rely on pollination and fruitification by flower pollinators such as insects, and in Japanese agriculture it is estimated that this generates an economic value of around 470 billion yen. Generally, whether it is possible to make use of many natural flower-pollinating insects depends on the natural environment surrounding the agricultural land. However, there was no method to evaluate this to date.

Previously, over the five years from FY2017 to FY2021, the research group was engaged in developing a method of surveying flower-pollinating insects that can be used at production sites of apples, pears, plums, pumpkin and bitter melon. In so doing, they obtained new information about persimmons.

Persimmons are plants native to China, and Japan is the number four producer in the world by volume (3.9%, calculated in 2017). They are dioecious plants, with male and female flowers blooming on one tree, but most cultivated varieties have huge numbers of female flowers only. The fruit set rate depends on the variety. For example, the quintessential sweet persimmon variety Fuyu has low fruit set potential.

As a result, persimmon plantation workers generally raise different persimmon varieties that have many male flowers for pollination within the plantation and introduce Apis mellifera L. (European honeybees). It was thought that natural flower pollinators also greatly contribute to pollination, but the extent of this was unclear.

Thus, the research group carried out a survey of the species and numbers of insects visiting persimmon flowers (flower-visiting insects) in the top 10 prefectures by persimmon production area (in FY2020). The survey recorded the numbers and species of insects visiting dozens of female flowers by eye while the female persimmon flowers were in bloom over two to three days, multiple times a day, for 30 minutes each time.

The results made it clear that across the country Bombus ardens ardens (bumblebees) or European honeybees were the main pollinators. The main species of flower-visiting insect varied between the plantations surveyed. The group saw cases in which the bumblebee was the major flower-visiting insect, even in areas where European honeybee nests had been introduced, and cases in which the European honeybee was the major visitor even though no nests had been established. European honeybee foraging behaviors extend over several kilometers, so it was thought that they had been introduced in other plantations, among other reasons.

Bombus ardens ardens are between 8 mm and 16 mm in body length, making them slightly bigger than European honeybees. They have rounded bodies, and other than their orange lower abdomen their bodies are black. They are docile in character and relatively easy to distinguish from other insects. They live across a wide area from Honshu to Yakushima Island, on plains and in mountainous areas. If the area around a plantation is urbanized, it becomes difficult for them to visit the flowers.

Moreover, in 2020 and 2021, the research group surveyed a Fuyu persimmon plantation in Ibaraki Prefecture, focusing on the number of pollen grains stuck to pistils with a single visit from one of these two insect species, and the resulting fruit set. For the survey, pre-flowering female flowers were covered with bags, which were removed once they flowered. After a flower visit by a bumblebee was confirmed the flower was once again covered with a bag, and after it had been fertilized 24 hours later the top of the pistil was removed to ensure there was no effect on fruit set, and the pollen grains were counted.

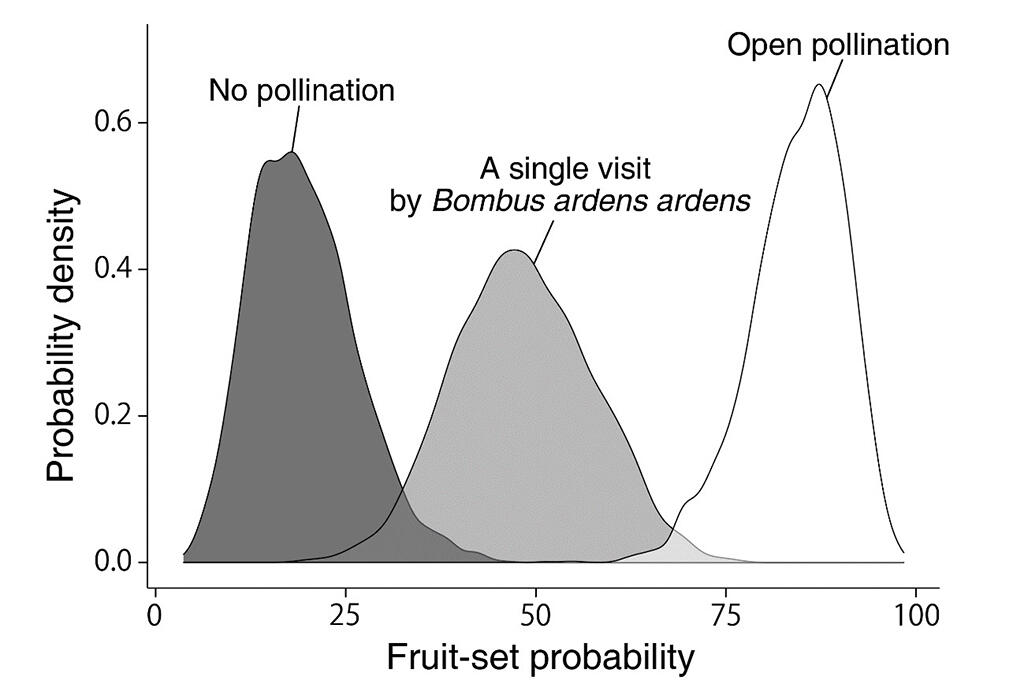

From their results, the group learned that the fruit set rate from a single flower visit by either insect species was around the same: both insects carried around 10-30 pollen grains to the pistil in a single visit. The group also investigated the number of pollen grains and fruit set rate for a non-pollination group, a single bumblebee flower-visit group, and a natural pollination group. The fruit set rate was estimated to be around 20% for the non-pollination group, around 50% for the single bumblebee flower-visit group, and around 90% for the natural pollination group. Investigating the correlation between the number of pollen grains stuck to the pistil and the fruit set rate showed the group that a 50% fruit set can be expected from around 27 grains being carried to a female flower, and two or three flower visits are needed for a fruit set rate of 80% or more.

Provided by NARO

The survey method in the manual differs from the survey method used for this research, and it is easier to use in the field.

Principal Researcher Kamo commented, "It was difficult to grasp the contribution of wildflower pollinators, so there are many cases in which the European honeybee was introduced to production areas for persimmons or fruit/vegetables that require pollination without considering the need for them. I believe that utilizing the manual we published recently will enable labor-saving cultivation that uses natural pollination services, using wildflower pollinator insects if there is an abundance of these, or, if there is not, by optimizing European honeybees, which should be introduced by region, to compensate. In the future, we hope to survey different areas and investigate whether we can provide indicators as to where we should introduce European honeybees."

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd.(https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.