Alloperla ishikariana Kohno, 1953, a species of stonefly, spends around two and a half years of its life as a larva in the hyporheic zone (the subsurface layer at the bottom of a river) before emerging as an adult insect and living for a period of around 10 days. A research group consisting of Associate Professor Junjiro Negishi of the Faculty of Environmental Earth Science, Hokkaido University, and his colleagues has carried out long-term fieldwork at the Satsunai River, a tributary of the Tokachi River in Eastern Hokkaido, to clarify their lifecycle. It is hoped that the results of this survey will shed light on the dynamics and biodiversity of animal groups in the hyporheic zone and lead to effective conservation in the future. The group's outcomes were published online in Hydrobiologia.

Provided by Hokkaido University

Rivers are subject to ranges of environmental stresses, such as deterioration of water quality, structural changes and rising water temperatures. To ensure that the diverse natural benefits of rivers continue, including water resources and recreation they provide, it is important to manage and use these environments with consideration for the habitats of their biota using the deep understanding humanity has gained of the natural structures of rivers and connections between organisms. However, there is a lack of information on a global scale when it comes to the behavior of biota in the area beneath a river (in the earth and sand of the riverbed).

One reason for this deficit of information is that surveys of these areas are physically difficult. With the continuous cooperation of the Obihiro Regional Office of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, the research group made use of heavy machinery to place sediment traps and PVC pipe observation equipment in the riverbed. Over more than five years, they collected aquatic invertebrates in different seasons, including January and February, the coldest time of the year.

They also collected adult aquatic insects with wings in traps placed at the side of the river. A native species of stonefly, Alloperla ishikariana Kohno, 1953 was investigated at the Satsunai River, a tributary of the Tokachi River. Using stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis, the group clarified the structure of the stoneflies' food web, estimated their growth speed, and gained an understanding of their age structure by measuring their body sizes under a microscope.

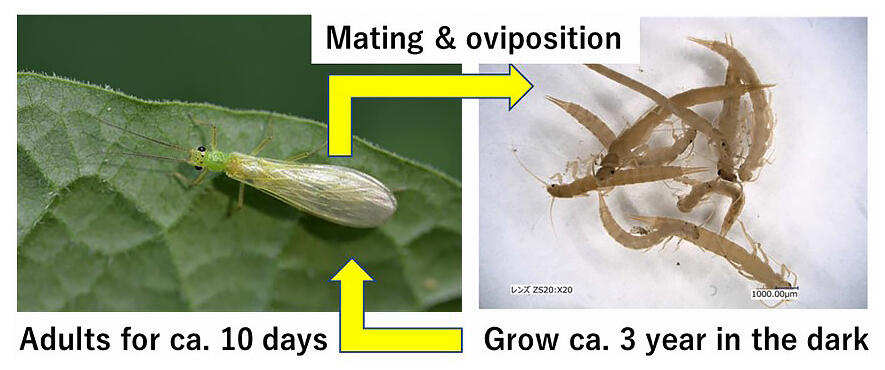

Larvae thought to have just hatched (body length of no more than 5 mm) appeared at a depth of 30-50 cm underground from around November. Based on close investigation of the chronology of body size, the group was able to confirm three different generations of this lifecycle stage during the fall and winter. It became clear that after growing for around two and a half years, the stoneflies gain their wings in the summer (June to July) and mate at the riverside.

The group has revealed, for the first time in the world, the stonefly lifecycle, in which adults live for up to around 10 days, while larvae spend a total of around three years underground after the adults have laid eggs. From the group's analysis of the food web structure, it is clear that Alloperla ishikariana are secondary consumers, preying on other organisms that coexist in the hyporheic zone (Chironomidae larvae and species of earthworm). Moreover, the group confirmed a tendency for the emergence of adult insects to occur earlier in years when the water temperature is high, and that many other species of aquatic insect larvae rely on the habitat underneath the stones of the riverbed.

Relevant books and guides in Japan often contain descriptions stating that the habitat of aquatic larvae of certain species of stonefly "is assumed to be the ground beneath rivers." This was because researchers had not found enough larvae in comparison to the number of adults collected. The results of this study have clarified that stonefly larvae have a lifecycle that involves waiting in the darkness beneath the stones with a great deal of patience before emerging in their adult stage. This result will contribute to the progress of further research that seeks to illuminate the lifecycles and roles of other species dependent on the hyporheic zone. It is also possible that this could be used to predict the effects of global warming on the lifecycles of aquatic animals. There are hopes that this will shed light on the dynamics and biodiversity of animal groups in the hyporheic zone and lead to effective conservation in the future.

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd.(https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.