The Japanese gecko (G. japonicus) is well known as a guardian deity of Japanese homes, but it is also distributed in eastern China. There have been suspicions that it is not a native species to Japan but in fact a non-native species. However, its history, including the period of its arrival, has been a mystery. A group led by Minoru Chiba, a doctoral student at the Graduate School of Life Sciences at Tohoku University; and Satoshi Chiba a professor at Tohoku University's Center for Northeast Asian Studies, have successfully inferred the process of the gecko's expansion into Japan from genome-wide mutation analysis and examination of ancient documents. The group's findings were published in the online journal PNAS Nexus.

Provided by M. Chiba, Tohoku University

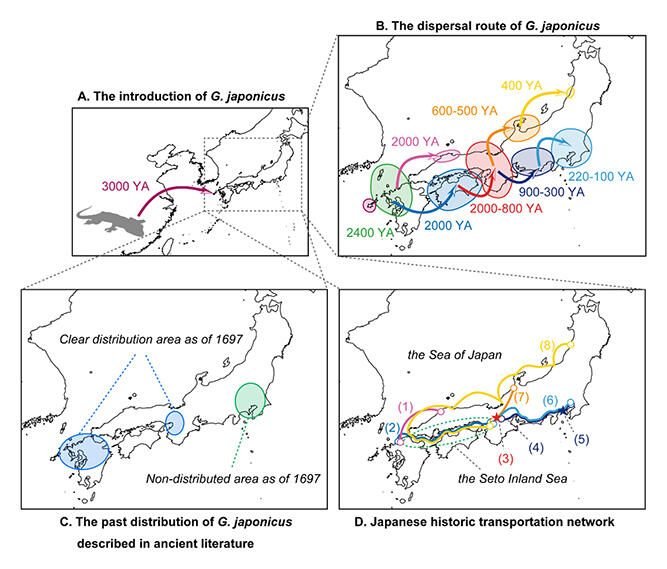

Based on a survey of Japanese archives and past research, the researchers found that although the word "gecko" first appeared in documents in a 1603 Japanese-Portuguese dictionary, the word "tokage" (Japanese for skink, meaning one who is behind a door) may have referred to geckos around the Heian period. From the Heian period to the Edo period, present-day lizards were confused with geckos and newts, and different documents described them differently. There was an ecological distinction between those found in grassy areas (present-day lizards), on the walls of buildings (present-day geckos), and in bodies of water (present-day newts). After 1603, these were clearly distinguished, and in 1697, the Honcho Shokkan, a pharmacology dictionary, stated that geckos were found in western Japan but not in the Kanto region.

Based on these findings, the researchers inferred that the Japanese gecko settled in western Japan by the Heian period and gradually expanded their habitat to eastern Japan with the development of Japanese society thereafter.

On the other hand, ddRAD-seq analysis revealed that Japanese geckos in the Japanese archipelago have undergone genetic differentiation in different regions. The researchers also found that all these local populations were created from a very small number of individuals from each of the ancestral local populations. This means that history repeated itself, with a small number of individuals migrating from their original habitat and created new populations.

The route and history of migratory dispersal of Japanese geckos were inferred from phylogenetic relationships of local populations, number of branched generations, and the timing of population increases and decreases. Japanese gecko migrated from China to the Goto Islands and then to Kyushu about 3,000 years ago. By the Yayoi period, about 2,000 years ago, they had begun their eastward migration from Kyushu via multiple routes, becoming established in the Kansai region by the end of the Heian period at the latest.

Later, a part of their migration continued eastward on the Tokaido Road and reached the Kanto region in the late Edo period and early Meiji period. This is consistent with the description in the Honcho Shokkan of 1697 that geckos were not yet in Kanto in the 17th century. Geckos also migrated from the Kansai region to Hokuriku during the Warring States Period, and in the Edo Period, they migrated from Hokuriku to Sakata, which was a thriving port of call for Kitamaebune merchant ships.

The history of the expansion of the distribution of the Japanese gecko, including the estimated migration routes and timing of the migration, shows many commonalities with the development of Japanese society, such as the development of the Kansai region in ancient times, including the construction of the capitals of Heijo-kyo and Heian-kyo, the shift to a monetary economy in the medieval and early modern periods, and the expansion of distribution networks through the establishment of shipping agents and other means. This suggests that the Japanese gecko dispersed with the expansion of human activities, taking advantage of human migration and the movement of goods to create its present distribution. The impact of humans on the distribution of plants and animals before the modern era is often overlooked compared to that of today, but it may have been greater than imagined.

The results of this research show that biodiversity, which is often viewed only within the framework of nature, has in fact had a long and close relationship with human society and has the history of human society as an element of it.

Journal Information

Publication: PNAS Nexus

Title: The mutual history of Schlegel's Japanese gecko (Reptilia: Squamata: Gekkonidae) and humans inscribed in genes and ancient literature

DOI: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac245

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd. (https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.