Project Research Associate Yusuke Watanabe and Professor Jun Ohashi from the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Science have proposed a model of population formation for mainland Japanese based on their analysis of genetic variations from Jomon people. Their model suggests that the regional differences in genotype and phenotype of modern Japanese result from differences in the degree of intermixing between Jomon and non‐native Japanese populations. These differences in intermixing can be traced back to the varying population sizes of different regions in prehistoric mainland Japan. The results were published in iScience.

Provided by The University of Tokyo

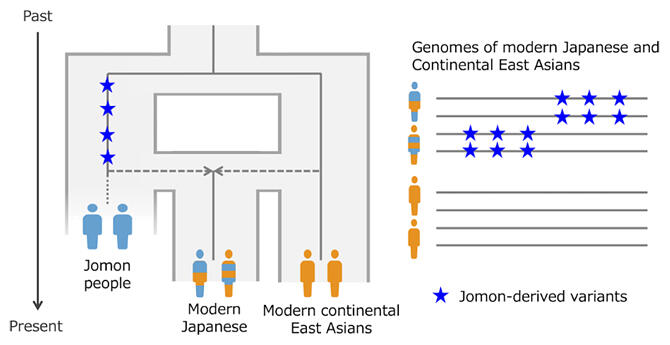

Recent studies on human genetics have revealed that certain regional populations in modern Japan share closer genetic ties with continental Asian populations, such as those in China and Korea, while others do not. This difference in genetic makeup is thought to be due to varying levels of intermixing between the Jomon and migrant populations. The research team concentrated on identifying genetic mutations in the genome of modern Japanese derived from the Jomon people (known as Jomon‐derived variations) and developed a methodology for detecting them. The research team then used single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) information from the whole genome of 10,000 individuals from each prefectural population in Japan to examine the prevalence of Jomon‐derived mutations. As a result, they discovered a geographic gradient in the degree of intermixing between the Jomon and migrant populations in modern Japan.

For instance, areas such as Tohoku, parts of Kanto, Kagoshima, and Shimane prefectures showed higher degrees of Jomon ancestry, while the Kansai and Shikoku areas showed lower degrees.

Furthermore, regions with higher population growth rates during the Late Jomon and Yayoi periods showed lower levels of Jomon‐derived mutations in modern times.

The researchers analyzed Jomon‐derived variations and found that the Jomon and migrant populations had developed phenotypes adapted to their respective subsistence patterns.

For example, the Jomon, hunter‐gatherers, were less dependent on a carbohydrate diet and may have adapted to this diet by maintaining high blood sugar and triglyceride levels. On the other hand, the migrants, who were agriculturalists, were genetically taller and more likely to have increased eosinophils and CRP (a protein that increases in the blood in response to inflammation).

They also found that the reason for regional differences in some phenotypes of modern Japanese is because the Jomon and the migrant populations each had distinctive phenotypes, and the degree of intermixing between the two groups in modern times differs between regions.

Based on these results, the team proposed a model for how the mainland Japanese race was formed from the Late Jomon period to the present when the regional diversity of mainland Japanese began to emerge.

Journal Information

Publication: iScience

Title: Modern Japanese ancestry‐derived variants reveal the formation process of the current Japanese regional gradations

DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106130

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd. (https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.