A research group led by postgraduate student Shiori Kinto and Assistant Professor Shuichi Yano of the Graduate School of Agriculture at Kyoto University, and Professor Toshiharu Akino of the Department of Applied Biology at the Kyoto Institute of Technology, has announced that the Tetranychus urticae, which cause extensive damage to crops, and its close relative, the Tetranychus kanzawai, avoid the traces of larvae of butterflies and moths that eat the same plants (silkworms, Theretra oldenlandiae, and Spodoptera litura). Avoiding the chemicals in larvae traces also ensured that this repellent effect lasted for more two days or longer. The results are expected to lead to the development of effective spider mite repellents and were published in Scientific Reports.

Provided by Shiori Kinto, Kyoto University

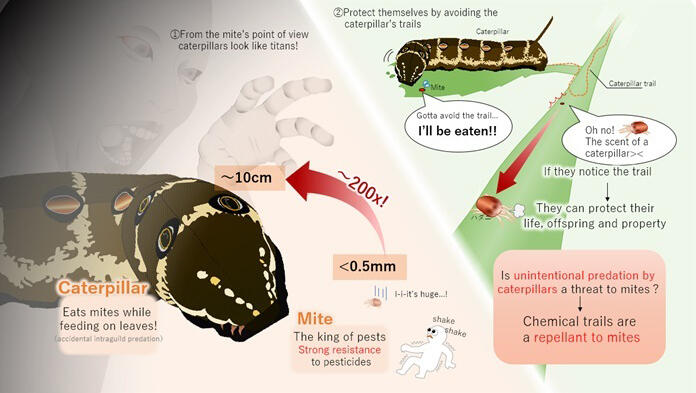

Spider mites are herbivorous mites with a body length of about 0.5 mm that suck the juices of plants and parasitize several plant species, causing damage to crops and fruit trees. They are designated as an important pest that is difficult to control due to its short generation cycle and susceptibility to drug resistance. Adult females of the Tetranychus urticae mite lay up to 10 eggs per day, or about a hundred over their lifetime, and live in groups in nests to protect themselves from ants and other predators. When the environment deteriorates, adult mated females migrate and form new populations.

Previously, the group had shown that the Tetranychus urticae and Tetranychus kanzawai avoid chemicals left in the traces of their predator ants, among other things.

In this study, the research group focused on accidental intraguild predation, in which the larvae (caterpillars) of plant‐eating butterflies and moths eat the leaves that the mites eat together with a population of spider mites. The speed at which caterpillars feed on leaves is as fast as 10 minutes per leaf, so if accidental intraguild predation occurs, the population is wiped out and the damage to spider mites is far greater than to their natural enemy, the Phytoseiid mite (which preys on 10 or more spider mite eggs per day).

The researchers investigated whether the female adults, which determine the settlement sites, avoid the leaves on which the caterpillars had walked. They used four species of caterpillars of different taxonomic families as caterpillars (Bombyx mori, Theretra oldenlandiae, Papilio xuthus and Spodoptera litura), and spider mites (Tetranychus urticae and Tetranychus kanzawai).

In the experiment, paired adjacent leaf squares were cut from a kidney bean leaf, and one caterpillar species was allowed to walk across one of the squares three times, and one spider mite species (one female adult) was placed in the center of the two leaves side by side to see which leaf it would settle on.

When all combinations were tested, all spider mites settled on leaves without caterpillar traces at significantly higher frequencies. They found that spider mites avoid caterpillar tracks even in combinations which they do not encounter in nature, and that spider mites avoid caterpillar traces in general. Further studies on how long these traces continue to repel spider mites, using silkworms and Tetranychus kanzawai, showed that they lasted for two days or longer.

When the repellent effect of the traces on actual plants was investigated with silkworms and Tetranychus kanzawai on kidney bean stems, the spider mites avoided the silkworm traces and climbed branches without traces.

They further confirmed that this repellent substance is a chemical that can be extracted with an organic solvent (acetone) and that Tetranychus kanzawai avoids it when it is applied to filter paper. The researchers are now seeking to identify these chemicals. If identified, this is anticipated to lead to the development of safe spider mite repellents that are less likely to become resistant.

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd. (https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.