Patients with cancer gradually become emaciated with disease progression. This condition, called cachexia, is characterized by muscle loss associated with systemic inflammation and is observed in most patients with advanced cancer. However, the pathogenesis of cachexia has not been fully clarified.

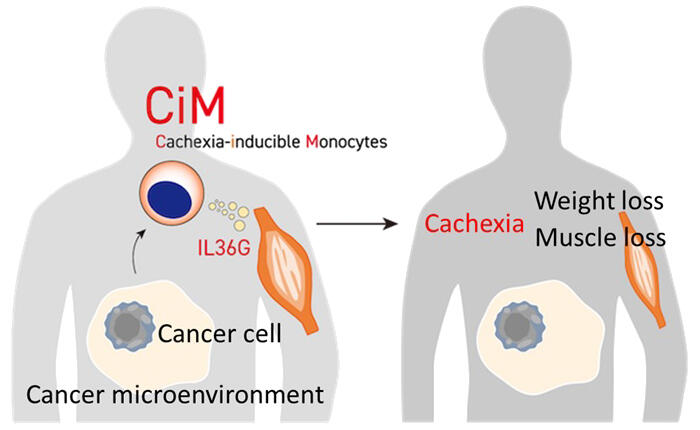

A research team led by Professor Hironori Harada of the School of Life Sciences at Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences, and Professor Yoshihiro Hayashi of the College of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Ritsumeikan University, have, for the first in the world, identified a specialized subset of monocytes (a type of white blood cells) that is not normally seen but emerges with cancer progression and secretes a cytokine called IL36G, which induces loss of muscle mass. They named this monocyte population cachexia-inducible monocytes (CiMs). Inhibition of IL36G function attenuated the development of cachexia in mice with various types of advanced cancer. The findings are expected to contribute to the development of new treatments effective for cancer cachexia. The work was published in Nature Communications.

Provided by Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences

Cancer cachexia is defined as "a multifactorial syndrome characterized by persistent loss of skeletal muscle mass that cannot be completely reversed with normal nutritional support leading to progressive functional disability." Cachexia is found in 80% of patients with advanced cancer, regardless of the type of cancer, and is a factor associated with the reduced effectiveness of treatment and deterioration of QOL. Cachexia accounts for about 30% of cancer deaths.

The research group focused on chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML). CMML is a blood cancer characterized by a persistent increase in monocytes. Patients with CMML often have symptoms of cachexia, such as weight loss and muscle atrophy. Because these symptoms are not common in other blood cancers, they hypothesized that a specific cell population responsible for cachexia exists among monocytes, which are increased in patients with CMML. In response, the research group established a mouse model of CMML and analyzed it in detail.

This model, established using the NUP98-HBO1 fusion gene identified in patients with CMML, exhibits CMML-like features, including increased monocytes and weight loss. Close examinations of these mice revealed that they had more severe muscle atrophy and muscle weakness compared to healthy mice. Pure monocytes from these mice cultured together with mouse myotubes (C2C12 cells) showed myotube atrophy. This result implies that special cells capable of decreasing muscle mass are found among monocytes, which are increased in CMML mice.

RNA sequencing was performed to assess the expression levels of all genes in monocytes, revealing that several genes were upregulated specifically in monocytes from CMML mice exhibiting weight loss. Flow cytometry and other methods were used to verify whether those genes were actually expressed as proteins in monocytes. These results led to the identification of a specialized cell population characterized by expression of the CD38 antigen, which is not found in the monocytes of healthy mice, and production of a cytokine called IL36G, which causes muscle atrophy, in monocytes of CMML mice with cachexia.

To better understand the characteristics of the discovered cachexia-inducible monocytes (CiMs), they performed single-cell RNA sequencing. As a result, CiMs were shown to be a distinct subset of monocytes with neutrophil-like properties. The research group also found that CiMs emerged just before weight loss began and that stimulation of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) was important for the induction of CiMs. Proteins such as HMGB1 and S100A9 have been reported to be elevated in the blood of patients with advanced cancer. These proteins may be involved in the induction of CiMs because they are known to stimulate TLR4.

An increase in blood monocytes is reportedly associated with a poor prognosis in patients with various solid as well as blood cancers. Therefore, they analyzed mouse models of breast and skin cancers and found that CiMs emerged in association with cancer progression, causing cachexia. Furthermore, they analyzed the data on gene expression in monocytes from patients with colon cancer and those with kidney cancer and confirmed that CiMs emerged in association with cancer progression. These results suggest that the emergence of CiMs causing muscle loss is a universal phenomenon common to cancer cachexia, regardless of cancer type.

The research group tested whether CiMs and IL36G can be therapeutic targets for cachexia in advanced cancer mice by suppressing IL36G production in monocytes and inhibiting IL36 receptors in muscle. The results confirmed that inhibition of CiM-associated IL36G function attenuated the onset of cachexia.

Currently, no treatments can dramatically improve the muscle loss observed in cancer cachexia. This discovery is a crucial step toward the development of new therapies for cancer cachexia. Antibody drugs against IL36 receptor and CD38 are already used for the treatment of inflammatory diseases and blood cancers. The time and cost for developing new therapies could be significantly reduced if these therapeutic antibodies with proven safety and pharmacokinetic profiles in humans can be applied to the treatment of cancer cachexia through successful drug repositioning in the future.

Journal Information

Publication: Nature Communications

Title: IL36G-producing neutrophil-like monocytes promote cachexia in cancer

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51873-x

This article has been translated by JST with permission from The Science News Ltd. (https://sci-news.co.jp/). Unauthorized reproduction of the article and photographs is prohibited.