"Eeeeeek!" I hear a family member scream and come running to the living room to find a small bug on the wall. I am sure many people have had this kind of experience. There seem to be a lot of individual differences, but most people dislike bugs. How come? Perhaps because they are creepy? But why? One perspective, revealed by a research group from the University of Tokyo, is that the widespread modern human hatred of bugs is because we see them indoors rather than outdoors due to urbanization and that we can no longer distinguish between bugs species. The group got this research result through a large-scale survey of 13,000 people. They see the hatred of bugs as even being connected to biodiversity conservation and have also proposed countermeasures.

Many bugs are not high risk

Feelings of dislike for insects, spiders, and other bugs are found worldwide and are especially prominent in developed countries and cities, but we did not understand the cause.

(Photos provided by the University of Tokyo)

"Negative human emotions can be broadly divided into fear and disgust. Fear is an emotion that makes us avoid something that could cause us direct physical harm, and in the case of bugs, this is limited to hornets or similar creatures. On the other hand, disgust is an emotion that makes us avoid infections and pathogens that are invisible; we know from various studies that we develop this feeling over anything high risk."

Dr. Yuya Fukano (ecology), Assistant Professor at the Institute for Sustainable Agro-ecosystem Services, the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, the University of Tokyo, offered this explanation. He went on to talk about how he took on the challenge of research about the hatred of bugs. "There are not actually that many bugs that pose a high risk for infection. However, nowadays, there are a lot of people who 'hate all kinds of bugs.' I became interested--what is this discrepancy? Why are bugs so hated?"

Two hypotheses from the perspective of evolutionary psychology

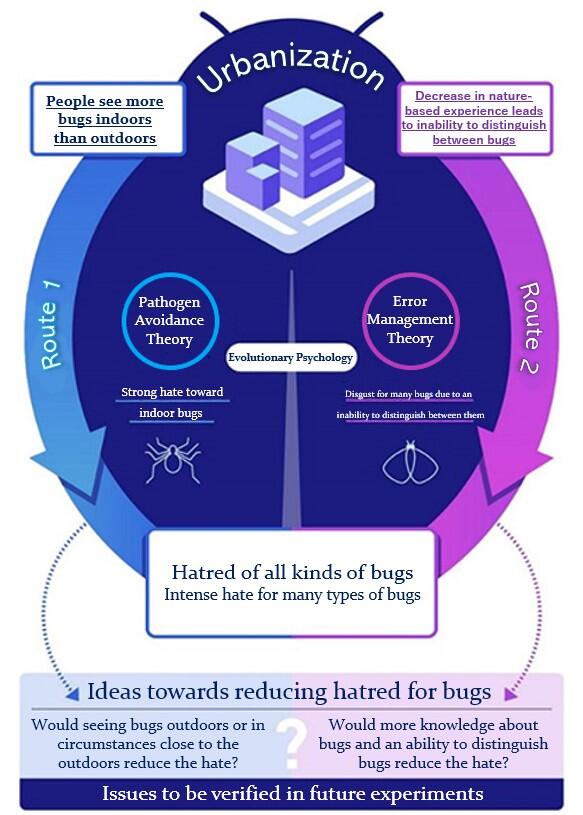

Thus, Fukano and Dr. Masashi Soga, Associate Professor at the Department of Ecosystem Studies of the same graduate school, focused that most hatred of bugs is a feeling of disgust and that people in urban areas have more negative feelings toward bugs. From the perspective of evolutionary psychology, which looks at the formation of psychology per human adaptions in the evolutionary process, they hypothesized that "urbanization has increased the hatred of bugs."

This hypothesis comprises two things. The first assumes that as urbanization has advanced, the bugs outdoors have decreased, while the chances of seeing bugs indoors have increased, making this a factor. As bugs enter the living spaces where we eat and rest, it has become easier for them to approach us, touch our skin, and get into our mouths, which increases the risk of infections. Because of this, we feel stronger disgust than when the bugs are outdoors, which follows the pathogen avoidance theory of disgust, saying that disgust is a psychological adaption that makes us behave to avoid pathogens. Here, the intensity of the aversion seems to vary depending on the risk of infectious disease.

The other one rests on "error management theory." These words may sound unfamiliar to you. The theory states that between "false positives" (you judge something as dangerous when it's not.) and "false negatives" (you decide it's not dangerous when it is.), judgments tend to be biased toward "false positives," which are less costly, meaning a safe error. According to the theory, we avoid anything that we feel poses even the slightest risk of infection. And also, the greater the uncertainty, the greater the bias toward false positives. Thus, as city dwellers lose their knowledge of the natural world and cannot distinguish between different kinds of bugs, they may develop an aversion to even those bugs they do not need to avoid.

Rhinoceros beetles are "exceptional," others are...

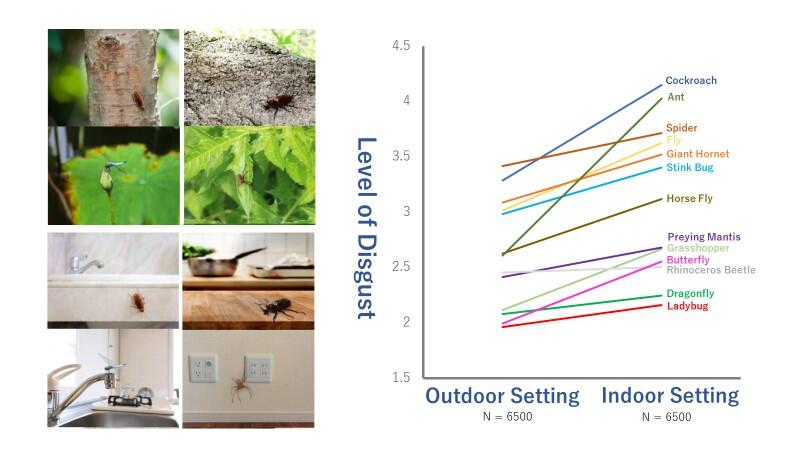

To verify these hypotheses, Fukano and his colleagues carried out a survey questionnaire of a total of 13,000 people aged 20-79 across Japan. First, they asked the questionees about (1) the urbanization degree of where they lived as a child and where they live now on a scale of seven levels, (2) whether they see 13 types of bugs more outdoors or indoors, and (3) the names of the bugs in the photographs, to test their ability to identify them. On top of this, (4) the questionees were shown the same images of various bugs-- half against an outdoor background and the other half against a synthetic indoor setting and asked whether they found each disgusting or not.

The outcomes tell that bugs that can live in any city, such as cockroaches, flies, and spiders, are often seen indoors, as expected. The people who saw the images of bugs against an indoor background blatantly showed stronger disgust than those who saw the same pictures of bugs against an outdoor setting. That backs the first hypothesis: "Due to urbanization, bugs are more seen indoors than outdoors, which has increased our disgust towards bugs."

For comparison, the one exception was the rhinoceros beetle--the level of disgust was much the same whether it was indoors or outdoors. "This is because we have a culture of keeping these indoors, like dogs or cats, making it normal for them to be indoors," says Fukano.

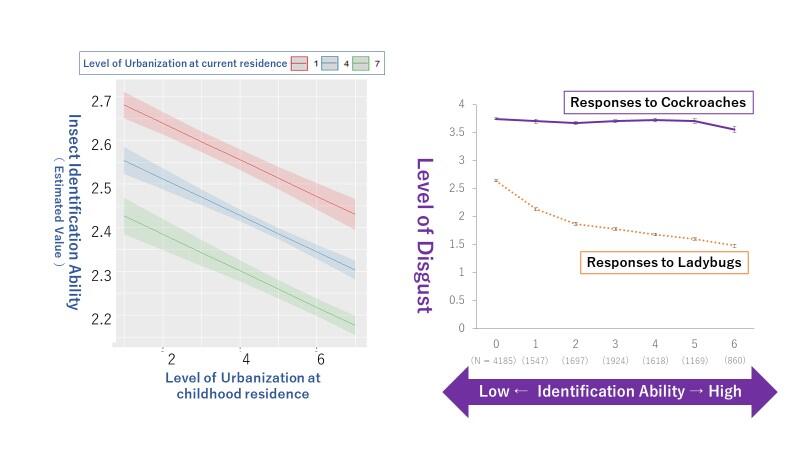

(Provided by the University of Tokyo)

In addition, the questionees with higher levels of urbanization in their childhood and current residence were less able to identify the bug species. Those who had higher bug-identification abilities indicated a clear difference in their feelings toward different types of bugs and, for example, felt disgust for cockroaches but not so much for ladybugs. In contrast, those with low bug-identification abilities had a strong tendency to hold intense hate even for ladybugs. That indicates that the experience of nature is in clear relation to the ability to identify bugs. The result is highly consistent with the second hypothesis that when bug-identification abilities decrease due to urbanization, people hate most bugs.

"This is the best explanation of the cause to date"

The survey outcomes have backed the hypotheses; they reveal that urbanization has brought bugs indoors, making it impossible for people to distinguish between different types of bugs, reinforcing the aversion to bugs. That suggests that the hatred of bugs is due to psychology formed under evolution to make us avoid pathogens and this has become even more intense due to urbanization.

However, Fukano and his team held back from making a clear-cut announcement that these outcomes "clarified the cause of the aversion to bugs". The subtitle of his press release had a sense of modesty, saying "Proposition and Verification of New Hypotheses." "I believe that we have the best explanation for the cause of the hatred for bugs to date. However, it is surely not caused by urbanization alone. For example, our survey didn't verify family factors, such as parents or siblings, or individual traumas at all. So, we thought it would be better not to be too conclusive," he says. At the very least, it' safe to say that he has established the keyword of "urbanization" as the primary cause of the hatred of bugs.

The survey outcomes were posted in the electronic edition of "Science of the Total Environment," an international specialist journal on environmental science, and released by the University of Tokyo on March 12.

Hating bugs could be the factor that prevents the progress of biodiversity conservation

Of course, liking or disliking bugs is the freedom of the individual. If you hate them, it is okay to live life avoiding them. However, Ecologists and biologists view the hatred of bugs as one reason that conservation of insect biodiversity is not progressing. Fukano explains, "In discussing the causes and countermeasures, we often talk about the negative image insects have and how improving that image is a challenge."

From these research outcomes, Fukano and his colleagues have proposed measures that might alleviate the hatred of bugs: People to see bugs outdoors and increase their knowledge of bugs in order to learn to distinguish between different species.

"For that to happen, efforts should be made not to reduce the number of outdoor bugs even in urban areas, including through exhibitions. The feeling of disgust may also change through education about bugs in kindergartens and nurseries. In the future, I would like to verify the effects of these things," says Fukano.

I am not disgusted by bugs, to the extent that I even greet them if I see them indoors. I'm starting to feel that it's essential to "educate" my family about bugs so that both the bugs and I won't be subject to their screaming.

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.