The more I learn about how creatures manage to survive in the harsh natural world through scientific articles and TV programs, the more impressed I become. It has become clear that a tiny species of wasps is developing a surprising cooperative relationship to leave more offspring. An international research group led by Meiji Gakuin University has discovered that the wasps have offspring sex ratios according to the number of females laying eggs and their familial relationships. It is the first time that such a type of creature has been found.

Only 2% of offspring are male?: "Inexplicable" wasps

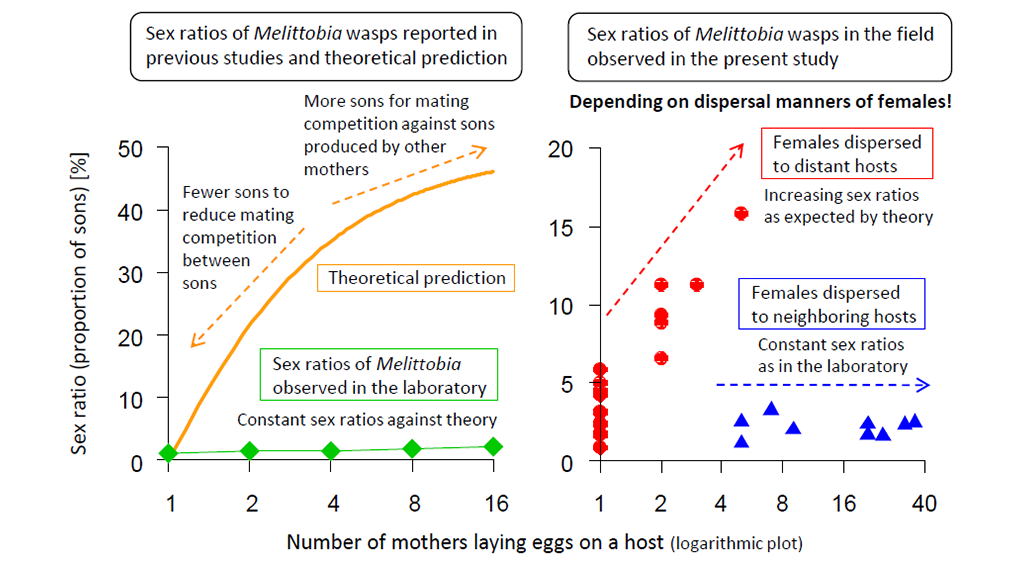

In general, the ratio of male to female children produced by females evolves to most efficiently allow her offspring to thrive. Organisms that interbreed with a male/female that they grew up together with will have fewer sons to avoid competition to get a mate. However, when females spawn with other females, they will produce more sons in preparation for competition with the sons of strangers.

(Provided by Meiji Gakuin University)

However, it has become known that "Melittobia," a 1-2 mm long wasp that is parasitic on the pupae of other wasp species, produces fewer sons, only 2% of offspring, even when laying eggs with other females. The reason is a total mystery. Other parasitic wasps, like most living creatures, produce fewer sons when spawning alone and more sons when more females are laying eggs together. What an inexplicable existence!

Female wasps are able to select gender at birth. Fertilized eggs produce daughters, and unfertilized eggs become sons. So, without mating, a son is always born. When they mate, females store sperm in their bodies and choose whether or not to fertilize them when they spawn, and if they do, a daughter is born.

The most efficient way to leave offspring

Jun Abe (evolutionary biology), a researcher at the Center for Liberal Arts, Meiji Gakuin University, and his colleagues, who have been studying Melittobia for many years, are the ones who took the challenge of unraveling this mystery. They examined Melittobia in their natural habitat and investigated the offspring ratios of the wasps after they laid eggs on the pupa of other wasp species.

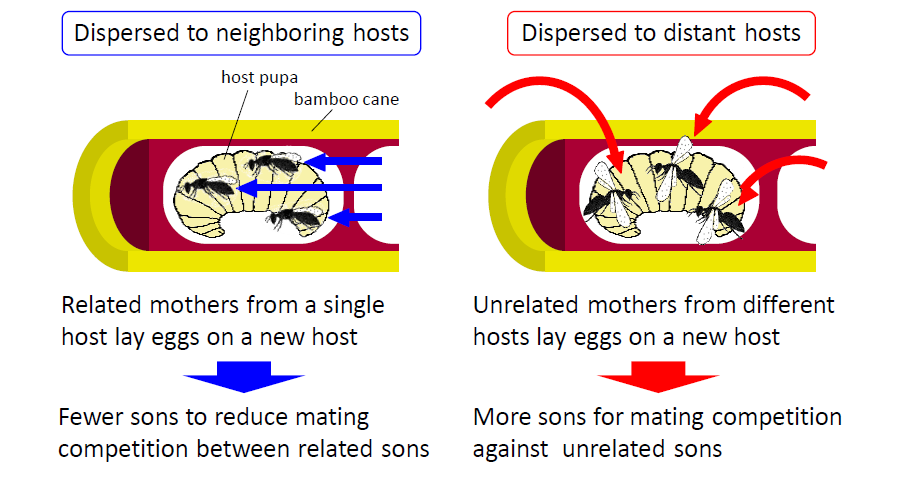

As a result, females who laid eggs after moving to nearby pupae gave birth almost exclusively to daughters, regardless of the number of females who laid eggs together. Up to here, it is consistent with what had been understood of Melittobia. After a DNA analysis it was shown that females who laid eggs close to each other were relatives, while those that spawned far away were strangers.

Because previous studies had been conducted in the laboratory, not in a natural environment, no females dispersed to distant locations. Hence, no cases with a high percentage of males arose. As with most living creatures, female Melittobia, who spawn at remote locations, are thought to produce more sons for competition. On the other hand, when they lay eggs nearby, they cooperate to produce fewer males and more females to avoid competition between males, not only their sons but also their male relatives.

(Provided by Meiji Gakuin University, with some modifications)

They also analyzed a mathematical model that assumed that the familial relationship between females changes depending on whether they dispersed or not. They then theoretically confirmed that the ratio of male/female choice, which they obtained in this observation, would allow each female to leave offspring most efficiently.

In addition, for Melittobia that stay in the laboratory and never disperse, cases where sisters and unrelated wasps spawned together were compared and there was no difference in the proportion of males and females born. This suggests they are not able to determine their kinship by smelling each other. They likely adjust the number of sons and daughters by estimating whether or not they have dispersed to distant places.

On a side note, they say that parasitized pupae are devoured and cannot hatch. The natural world is harsh.

(Provided by Meiji Gakuin University, with some modifications)

An overall understanding the social behavior of living creatures

This is the first time that any creature selectively choosing offspring ratios according to the number of surrounding females and their familial relationship has been confirmed. Abe says, "As females are the ones who lay eggs even if there are few males, they can mate with those females. Then, if each mother produces many females, they can efficiently increase their offspring. Despite that, when mothers are strangers, they will selfishly give birth to more sons. On the other hand, we have found that they act in a win-win relationship if they are close relatives.

The research group consists of Meiji Gakuin University, RIKEN, Gifu University, Keio University, and Oxford University. The results were posted in the electronic edition of "Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences" on November 11 (Japan time).

They intend to continue their research to see if other wasps have selective offspring sex ratios based on familial relationships. They also aim to clarify the specific method by which Melittobia recognize when they have dispersed far away. Abe says, "This discovery applies not only to understanding wasp's gender choice birth but also to understanding overall social behavior, such as on what occasions living creatures behave selfishly or cooperatively."

Sometimes we can maximize our interests by cooperating instead of fighting all the time. An insect of only a millimeter or two long has made us think about our own situation.

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.