It is said that approximately 30 million tons of plastic waste flow out into the environment annually, of which approximately 2 million tons flow out into the sea and become marine plastic. Although there are concerns regarding the adverse effects of marine plastics on the ecosystems, the diffusion route and the exact amount of these plastics floating in the ocean remains unknown. Professor Atsuhiko Isobe of the Oceanic and Atmospheric Research Center, Institute for Applied Mechanics, Kyushu University, is attempting to clarify the true extent of the situation in collaboration with Thailand, which is considered to be one of the major sources of marine plastic waste. Based on scientific evidence, the project aims to formulate policies for waste reduction that are acceptable to the local people.

Professor, Oceanic and Atmospheric Research Center, Institute for Applied Mechanics, Kyushu University

Principal Investigator at SATREPS since 2019

Predicting sources of plastic waste using ocean current models

Cleaning up with locals and verifying results

The topic of marine plastics has been continuously discussed for some time now but plastics continue to be manufactured in large quantities, and approximately 2 million tons of plastic continue to flow from rivers into the sea each year. It is said that 80% of this waste comes from Asian countries, which have been developing rapidly in recent years. Of particular concern are "microplastics " that is, plastic that have broken down to a size of 0.5 mm or less. Because of their light, small, but robust nature, microplastics can float almost anywhere in the world. Recently, they have even been discovered in the Antarctic Sea, where human population density is at its lowest. There is no longer any doubt that the oceans of the world are heavily polluted and research on the effects and toxicity of pollution on marine ecosystems is being actively conducted worldwide.

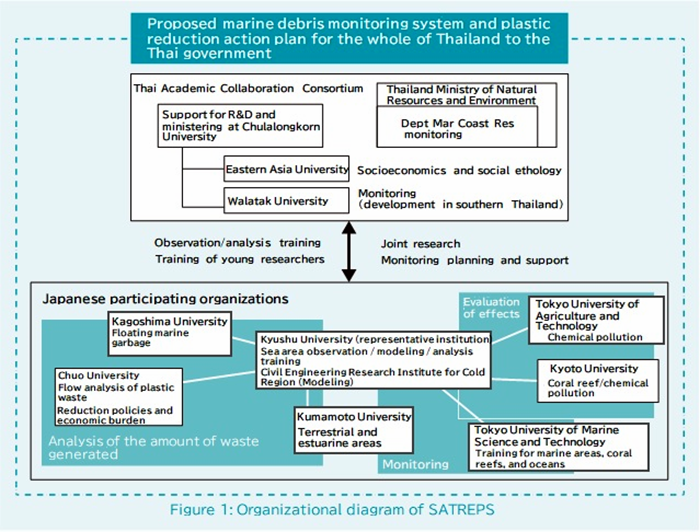

Professor Atsuhiko Isobe of the Center for Oceanic and Atmospheric Environment, Institute of Applied Mechanics, Kyushu University, was one of the first to notice the problem of marine plastic and lead research on this topic. Currently, he is conducting joint research with Thailand with the support of the Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS) program, jointly run by Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) (Fig. 1). In Thailand, the amount of plastic waste has increased rapidly; it currently ranks as the 5th highest generator of plastic waste per capita in the world. Concerns regarding the impact of this waste generation on tourism and fishing, which are the country's main industries, are coming to light. Prof. Isobe and his Japanese team are conducting empirical research in collaboration with Thai authorities, aiming to formulate policies for waste reduction based on scientific data.

Prof. Isobe began studying marine plastic more than a decade ago. Originally, he was a physical oceanographer who studied ocean currents in relatively shallow waters such as the East China Sea and the Seto Inland Sea. At first glance, this research area seems to be quite distant from research on marine plastics. "The trigger was noticing the drifting garbage scattered along the beautiful coast of the Goto Islands in Nagasaki Prefecture. Looking at their labels, I noticed that much of this trash was from overseas products; therefore, in 2007, I started research to clarify the origins of these products, " Prof. Isobe recalls.

First, the source of the waste was estimated by playing an ocean current model reproduced on the computer in reverse. To verify the obtained results, the researchers also conducted a survey of the litter that actually washed up on the beach. The islanders of the Goto Islands were hired using research funding to collect and classify all the litter on the shore at a frequency of once or twice a month for two and a half years. Countries of origin were confirmed by examining the languages written on the packaging, and the researchers confirmed the high accuracy of the simulation.

East Asia is a hotspot

Establishing and standardizing survey methods

During the investigation, Prof. Isobe noticed something. "I found a lot of small pieces of plastic. Nowadays, these small pieces are recognized as a significant problem, in the form of microplastics, but at the time, no specific name had been assigned. There were few research reports on this topic and I became really interested in this issue, " he said. In 2010, Prof. Isobe joined Ehime University, and in 2014, he moved to Kyushu University. Since then, he has continued marine research in cooperation with Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, Nagasaki University, Kagoshima University, and Hokkaido University. A 2014 survey reported that the floating density of microplastics in East Asia, mainly in the Sea of Japan, is very high; it is 27 times higher than in other waters globally. As a result, East Asia is considered a "hot spot " for microplastics. A 2017 survey also revealed for the first time that microplastics have reached the regions surrounding Antarctica.

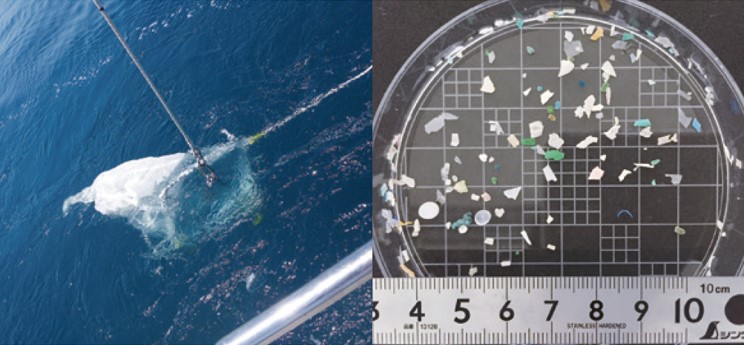

Prof. Isobe continued to improve the survey method while proceeding with marine surveys. 10 years ago, at the start of his research, there was little published content, and even if the survey method was described, the content was often ambiguous. "I wanted to conduct a fact-finding survey on how much microplastic is in each sea region, but there was almost no past survey data. We had to start by establishing a research method through trial and error, " he says, discussing his past hardships. For example, it is not enough to write "I pulled a net for 10 mins by ship " as a method of investigating the pollution status of microplastics. This is because the amount of seawater collected differs depending on whether it is pulled against or along the ocean current. Without knowing this amount of water, the density of plastic cannot be calculated, and the degree of pollution cannot be accurately evaluated.

In response to these challenges, the researchers had to slowly establish methods one by one. For example, they developed a method for collecting surface-level matter using a net, called a Neuston net, designed to capture planktonic organisms and devised a method to collect data on ocean flow by attaching flowmeters to the net. Since the mid-2010s, the established research methods have been compiled in collaboration with domestic and foreign researchers and were published as guidelines issued by the Ministry of the Environment in 2019. These guidelines also extend to post-collection analyses.

Previously, researchers used tweezers to manually separate plastic from seawater containing a variety of suspended solids. However, it is not easy to determine whether these separated materials are plastic by simple visual observation. Therefore, to determine whether the object is plastic, the researchers adopted a method using an analyzer called a Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (FTIR) to improve the efficiency of the survey. "Currently, researchers worldwide are conducting studies according to these guidelines. If you do not follow the guidelines, your research paper will no longer be accepted. These methods have been established through trial and error and are becoming standard practice globally," he says proudly.

Joint research with Thailand initiated

Demonstration of waste reduction plan

As the true extent of marine plastic pollution becomes clear, there are increasing calls for countermeasures from Asian countries, which are the main sources of pollution. China and Southeast Asian countries have increased their production owing to rapid economic development, but there are not enough waste incineration facilities in these countries. However, Prof. Isobe points out that establishment of facilities alone is not enough. Even if there is are sufficient facilities, it will not work without a system in which the user properly separates garbage and transports it to a disposal facility. "We also have to reflect on why plastic is used in the first place; it is cheap, durable, and hygienic. If we take unreasonable measures such as banning the use of plastic altogether, people in less fortunate positions may suffer one-sided disadvantages, " explains Prof. Isobe, regarding the difficulty of countermeasures.

Prof. Isobe said that he learned about the call for SATREPS projects when he was considering the utilization of the research results obtained from previous studies to solve social issues. One of the characteristics of the international cooperation program is that it does not unilaterally provide technology to the partner country but produces results together through joint research. "In Thailand, there was a paper reporting the effects of marine plastics on coral, and there were researchers working in this field. I heard that both the country and the people are highly interested in tackling the challenge of marine plastics and I thought they could be an ideal partner," he says, speaking on the circumstances that led him to this project.

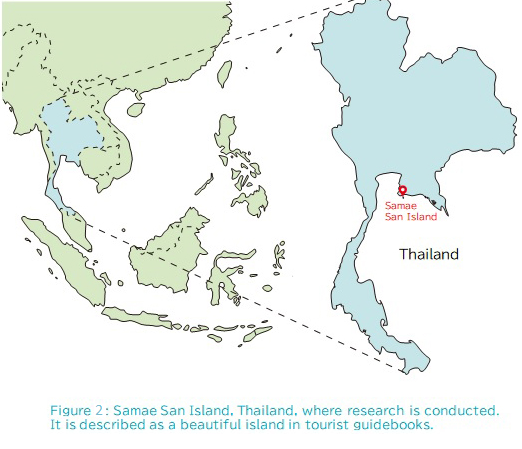

Joint research has begun with Professor Voranop Viyakarn of the Department of Marine Science, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, as a partner. After conducting a fact-finding survey to clarify the process of discharged plastic waste ending up as marine plastic, researchers will create a waste reduction plan that suits the lifestyles of the local people. The plan is to conduct a demonstration experiment and finally prepare a policy proposal. The site for their plan will be Samae San Island, which is located approximately 180 kilometers south of the capital city of Bangkok (Fig. 2). It is an island where tourist destinations with beautiful coasts and medium-sized towns coexist. Some people put out garbage, and there are also beaches onto which garbage from the neighborhood flows. The site was recommended by the Thai team, saying that it would be suitable for tracking the outbreak.

When Prof. Isobe actually visited and inspected the island, the tourist areas were clean and there was no garbage. However, in the residential area where the local people live, the garbage could not be completely disposed of and he saw how it was overflowing. "I thought it was a town typical of Southeast Asia. It was also great that the entire island was able to cooperate in this research. If the efforts to reduce waste are successful here, these methods will work not only in Thailand but also in other Southeast Asian countries. It will become a plan that can be realized in many towns, " says Prof. Isobe.

Calculation of total volume using drone radiography for efficient wide-area surveillance

Unfortunately, COVID-19 spread just before the investigation was started on Samae San Island. Prof. Isobe was forced to suspend his research and decided to advance technological development for wide-area surveys of plastic garbage in Japan. "It is not possible to get a complete picture of the whereabouts of plastic waste just by visual observations. Although such surveys give good data, it only makes sense if they are continued on a regular basis. We needed to develop a method that would allow us to continue investigating a wide area without spending money," he says.

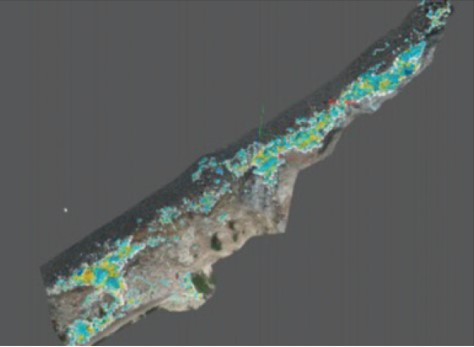

The development was conducted by a team led by Associate Professor Shin'ichiro Kako of Kagoshima University. Emphasis was laid on three points: the motivation to measure a wide range of beaches in a short period of time, the objectivity to accurately determine plastic from diverse marine waste, and the versatility of use in various locations. Using drones, it is possible to measure 100 m2 in just 20 min. The measurement can be performed by anyone using a model that can acquire location information in real time or by automatic flight. Unlike natural objects, plastic is characterized by its unique colors and shapes. Therefore, using simulated waste, artificial intelligence (AI) was repeatedly trained to learn the characteristics of plastic waste, making automatic judgments possible. Plastics range from thin (like vinyl) to three-dimensional objects (like styrofoam). Even so, these researchers have made it possible to reproduce the three-dimensional structure from photographs taken from various angles and calculate its volume.

When the actual measurement was performed on the Ogushi coast in Nagasaki Prefecture, the error between the estimated value and the measured value was within 5%. Although the accuracy is slightly low for places where a large number of rocks are present, it is said that a 500 mL PET bottle can be detected when shooting from 17 m above the ground. "With this technology, long-term fixed-point observations will be possible with as little effort as possible. In the future, I would like to conduct outdoor measurements in a variety of environments to further improve accuracy, " says Prof. Isobe with a smile.

From the photograph (left) of the simulated plastic waste placed on the beach taken with a drone, AI identified only plastic waste by coloring it in red (right). Volumes are calculated from the inferred 3D shapes after reconstruction using footprint areas and heights. (Source: Kako et al., 2020, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 155, 111127.)

The drone used is equipped with a 20 million pixel camera, and the position data can also be measured. Data obtained from manual classification of floating garbage was fed into an AI system, enabling it to discriminate between garbage types automatically. The colored areas (blue, yellow, and white) are those where AI judged that waste was present.

(Source: Kako et al., 2020, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 155, 111127.)

Balancing economic development and environmental measures

Japan must get involved

The researchers are also considering using the system built into the drone as a smartphone application. When citizens find garbage in the city, they take pictures on the spot and the information is collected in a data center. This makes it possible to include not only coastal but also land-based plastic waste, and it is possible to understand what kind of waste is discharged when and where. By participating in surveys on their own, the hope is that citizens will become more aware of garbage disposal issues. By building upon these efforts, the route of marine plastic generation on Samae San Island will be clarified, and countermeasures for marine plastic pollution will be promoted. However, the situation is not going to improve immediately. "Just because we can identify effective measures, it will not work if we, as Japanese, suddenly fire off proposals to the local government. People in that country must properly discuss policies that suit their lives. However, it is important for us scientists to present scientific data upon which accurate judgments can be based," says Prof. Isobe.

Professor So Sasaki of Chuo University's Faculty of Economics, who has also stayed at Chulalongkorn University as a researcher in the past and is familiar with Thai environmental policy, has joined SATREPS. With the cooperation of Prof. Sasaki's research partners, the group plans to pave the way for proposals to the Thai government. If the efforts in Samae San Island prove successful, it will be used as a model that combines economic development with environmental measures in the countries of Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Africa, where further economic development is anticipated. "Currently, the world is moving toward the elimination of plastics and disposable products. Japan is not independent of this trend and charging a fee for plastic bags is only the beginning. Each individual is required to reduce the amount of plastic they use," he says. Prof. Isobe will continue to gather scientific evidence so that the world can take steps toward solving the problem of marine plastic pollution.