Adapted from a press conference held at the Japan National Press Club on June 17

In the 21st century, we are now grappling with the coronavirus pandemic. Given how advanced our science is today, I had hoped that we could deal with this situation more smoothly. However, now that it's happening, I realize that the situation is quite severe and there are many problems we must deal with.

Previous pandemics involving infectious diseases have occurred in the past; however, we managed to overcome them via acquiring herd immunity. I hope that Japan will also acquire herd immunity as soon as possible via vaccination, allowing the coronavirus situation to settle down. Viruses cannot live without a partner (host). Sometimes, for viruses to survive, they can be weakened, or humans develop tolerance (immunization), enabling pandemics to be brought to an end.

Those who have studied viruses have said that the new coronavirus is very difficult to handle and that further research on it is required in the future. People often speak of "winning the fight" against viruses. However, they have existed for far longer than humans, and our ecosystems have evolved to exist and continue living in a world containing viruses.

Life science has progressed, and I had thought that in the 21st century, we would be able to deal with a pandemic. I suppose I was mistaken. While we have always said that it could take up to 10 years for a vaccine to be developed, new technology (in Europe and America) has enabled the extremely rapid development of a vaccine. These and other findings suggest to me that the 21st century will be one of life science. However, I feel that there is a problem because Japan has not played an active role in developing the vaccine.

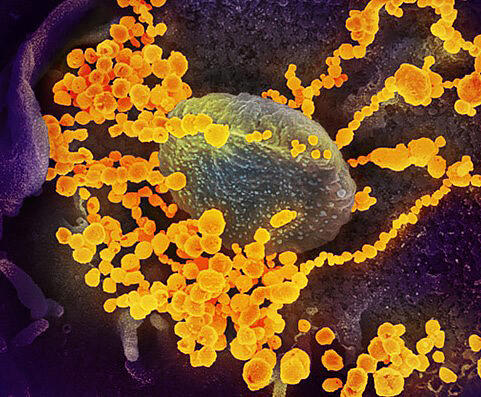

Currently, various mutant strains are spreading worldwide. These variants are a major factor preventing the end of the pandemic despite rising vaccination rates (provided by NIAID)

DNA research lets us ask, "What is life?"

As someone who has studied life science for a long time, there is something I would like all of you to know. The Japanese word for "life science" itself is not very old, being coined in 1970. This is the word that my teacher proposed when he created the Institute of Life Sciences. For a long time, biology was divided into zoology, botany, and other localized disciplines. However, after we discovered the existence of DNA, we have been able to truly ask, "What is life?" Until this achievement, we could not study humans inside a biological laboratory as living creatures and research on humans was deemed as anthropology up to that point. However, using DNA, we can study humans as living beings--this is the essence of "life science."

Life science has another meaning. In the 1970s, pollution and environmental problems emerged along with economic growth; therefore, biologists had to contribute towards creating a "life-based" society. During this period, the United States created the word "life science." The United States proceeded with the Apollo program in the 1960s; however, when President Kennedy was assassinated and replaced by President Nixon, he began the "Battle against Cancer" as the next project after the Apollo program. It was decided that biology and medicine had to be studied alongside one another. This field of "biomedicine," combining the two disciplines, was named "life science." Through translating this term into Japanese we get the word "life science" (seimei kagaku); however, the focus of this research in Japan is different.

While exploring new frontiers under the banner of life science, the United States also created bioethics and promoted scientific and technological advancement in medicine. Meanwhile, in Japan, the study of "life science" is focused on valuing a societal framework based around the concept of life itself. The majority of the "life science" research currently underway in Japan is of the American sort, and few researchers are aware of the Japanese-style of research. I do not mean to imply that the American style of "life science" is unnecessary. However, I think that as researchers we should continue to value the Japanese style of life science.

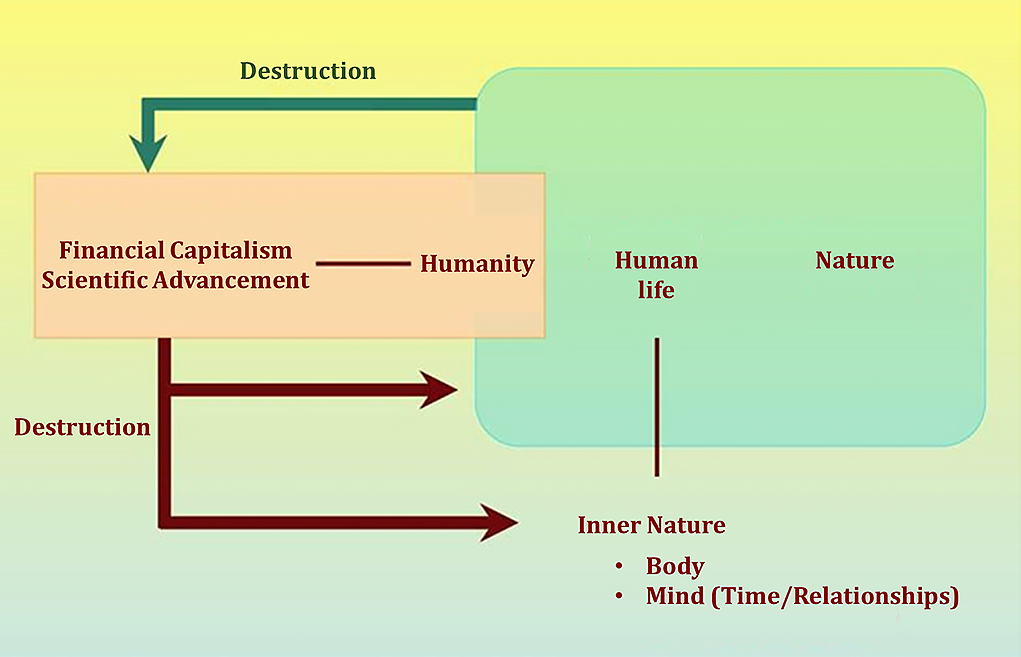

I would like to talk a bit more about this sort of life science style that we have created here in Japan. I think our society is a mix of financial capitalism, scientific technology and humanity. Human beings move money to make society more convenient with science and technology; however, as we can see from the coronavirus pandemic, human beings are also creatures of nature. Furthering this system of financial capitalism and scientific technological development will allow us to be happy; however, it will also damage nature. Today's environmental problems and unusual weather conditions represent the destruction of both the "outer" (environment) and "inner" natural worlds (humanity).

Humans exist as part of nature. Continuing to live on the principle of financial capitalism and scientific technological advancement will destroy human minds and bodies. This is currently happening. At the time of the 2011 earthquake, there was a science and technology related nuclear accident. The destruction was widespread and it has not yet been resolved. With the novel coronavirus disease, "inner nature" (body, mind) is damaged. I think it is important to think about society in this way.

Pondering 3.8 billion years of Biohistory

In the modern age, mechanistic theory prevails. During the 17th century, Galileo said, "The great book of nature is written in mathematical language," Bacon said, "Humanity has dominion over nature" and Descartes said, "Animals, including humans, can be thought of as machines." Newton said, "We shall delve into ever smaller worlds and analyze them." These ideas were the origin of mechanistic theory.

Without these people, science would not have progressed to where it is today. I admire them. However, it is vital for us to ask whether the mechanism of a bygone era is the only ideal upon which we should conceive of life and society in the 21st century. Rethinking the fact that humans are living things and a part of nature. I would like everyone to take this coronavirus disaster as an opportunity to think about it in society as a whole.

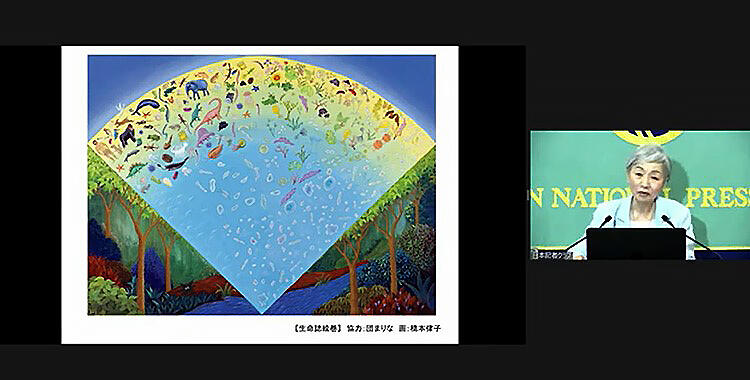

What we have begun here is "Biohistory." Life science's mechanistic worldview worries me. I think we should focus on DNA and cells and take a more life-oriented view of the world. The basics of this idea are shown in the Biohistory Emaki.

Living things are diverse. While we have only named approximately 1.8 million species of lifeforms, there are likely tens of millions of creatures in tropical forests and other regions yet to be fully explored. Thinking about the world of living things after learning about such diversity, I think that is what we should do now.

On the contrary, all living things are made up of cells that contain DNA. Modern biology states that all life came from one ancestor, one type of "ancestral cell." It is imperative for science to look at the big picture based on this commonality.

Looking at others as equals is the true essence of Homo sapiens

Mushrooms, sunflowers, humans, and dolphins would not exist without the 3.8 billion years of life history preceding them. For example, suppose you want to crush an ant. Doing so would be crushing the 3.8 billion years of evolution from our ancestor (ancestral cell) that created that ant. When thinking about life, I want us to think about this "sense of position." However, this begs the question of whether we can crush whatever we want or whether we should not kill anything. We kill other things so that we may live.

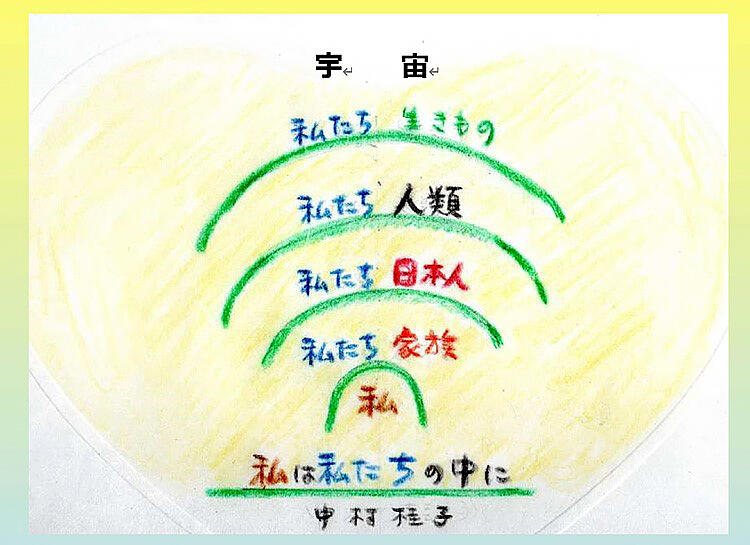

In the past, we believed that humans existed on top of bacteria, insects, and the other life forms that are on Earth. Now, we should realize that every living thing has 3.8 billion years of history behind it. We say that diversity is important for living things; however, aren't we looking at them from above? Humans living as they should, as a member of the kingdom of life. Looking around amidst the life that surrounds them. I think this sense of perspective should define us as Homo sapiens.

When we think about the world of living things, the word "us" is born. We should be conscious of "all of us living things." We should think of ourselves as individuals among the myriad of living creatures on this planet. We can situate ourselves amidst this vast bounty of nature. Viruses are part of this picture too. We (humans) live in a world of living things. That's what I think.

Bacteria and viruses exist inside us

I think that what we have to learn when an unexpected problem arises is to think in connection with nature. This was true for the Great East Japan Earthquake, and is true for the coronavirus pandemic.

There are countless microorganisms inside our bodies. Recently, gut microbiota have become a household name; however, microorganisms exist all over the body. In the past, these were called germs, things to be eliminated. Now, we know that without these things, our own lives would be impossible. When you or I refer to ourselves as "I," we are also referring to all these creatures.

Bacteria live together with us and support us. However, recently it has become clear that viruses are also always present in the body. There are trillions of bacteria inside each one of us. But I was surprised to learn that there are 380 trillion viruses inside each one of us as well.

"I" am composed of a truly alarming number of bacteria and viruses, among other things. I have always thought of myself as consisting of the DNA I inherited from my parents. However, the truth is that I live alongside the bacteria and viruses inside me, and because each of them has their own DNA, I consist of that DNA as well. The amount of DNA we receive from microorganisms and viruses is greater than the amount of DNA received from our parents. That is what comprises me. And you, too. That is what it feels like to live in a world of living things. I think that this feeling is important for our way of life after the coronavirus.

NAKAMURA Keiko

Born in 1936 in the city of Tokyo. Graduated from the Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, the University of Tokyo in 1959, and completed a graduate degree at the Graduate School of Biochemistry at the same university in 1964. After working as a researcher at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases and the director of the Human Nature Research Department at the Mitsubishi Chemical Life Science Institute, she became a professor at the School of Human Sciences, Waseda University in 1989. In 1995, she served as a visiting professor at the Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, the University of Tokyo, and in 1996, as a professor at Osaka University. In 2002, she was appointed Director of the JT Biohistory Research Hall, and in 2020, she was appointed Honorary Director. She has written numerous books, from "Life Science" (published by Kodansha) in 1975, to "Life Magazine (Biohistory)" "The Search for New Knowledge Learned over 3.8 Billion Years" (Fujiwara Shoten) in 2017.

(UCHIJO Yoshitaka / Science Portal Editorial Office, Kyodo News Visiting Editorial Writer)

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.