Established in 2001, Miraikan celebrates its 20th anniversary this year. With the next 10 years in mind, Miraikan has set out on a new journey, with the vision of "At Miraikan, together with you, we 'Open the Future.'" At the forefront of this vision are Science Communicators (SCs). Their role is to use their expertise and communication skills to communicate science and technology in an easy-to-understand way. SCs engage visitors who have various perspectives, in dialogues about the future society. One of Miraikan's essential missions is to train and produce SCs that actively serve as an interface between science and society. We take a closer look at the SCs who are endeavoring every day to connect science and society.

It's not just about "communicating correctly"

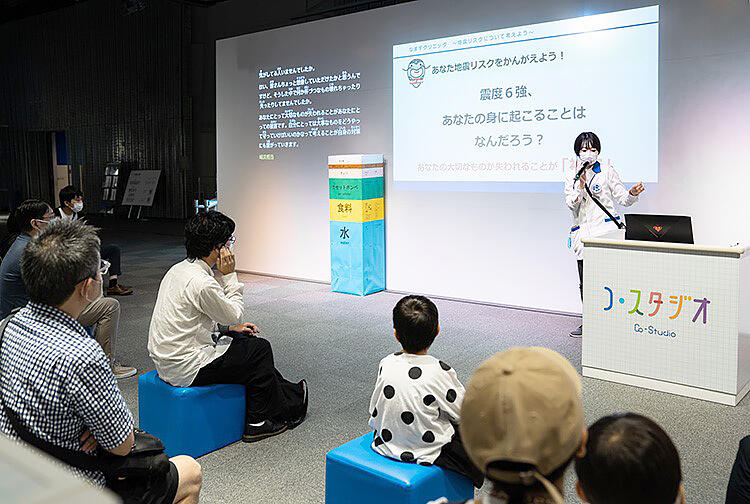

"What do you think is the probability of occurring a major earthquake of intensity six or higher (Japanese 'Shindo' Scale) at this location within the next 30 years?"

Asuka Takeshita, a SC, asked this in a "Science Communicator Talk" -- an event held on the exhibition floor on the fifth floor. While checking participants' responses, she explains the probability of being hit by a major earthquake in an easy-to-understand manner, comparing it to a traffic accident or cancer. Participants then can relate to the risks, considering the disaster as "their own event."

Takeshita studied agricultural engineering at university and graduate school and worked as a public servant after graduation. During that time, she experienced difficulty communicating with a diverse range of people, including locals and business people.

"When I read the SC recruitment page that said the job was about 'connecting various stakeholders,' I thought it might give me a clue to my challenge."

Takeshita is challenging the concept of science communication in a variety of ways based on her own experiences. NicoNico Live Broadcast is one of these.

"In the broadcast with the theme of the new coronavirus, I asked experts about how to deal with adverse reactions to vaccinations and conveyed their answers to viewers."

While it is interesting to get into different values through translating and communicating science, she feels more risk and responsibility in delivering information.

"For example, when I introduce data showing the infectivity of variant strains, some people think it's not a big deal, while others find it very scary. With so many different values, we may hurt others unintentionally. Keeping this in mind, I go through trial and error, changing the way of communication depending on the participants and suggesting ways to deal with the situation instead of just presenting data."

Creating a place where people can casually talk about science and technology

At the far end of the exhibition floor on the third floor, there is a round table, a few chairs, and a whiteboard with sticky notes on it. This is the "Dialogue Terrace," which Takeshita and other SCs jointly created.

"There are many 'questions' at Miraikan, but places to discuss them are limited. We created this place thinking it would be nice to have somewhere people can casually talk about science and technology, not only exhibitions and events."

Visitors can casually drop by and post sticky notes with their opinions on the whiteboard, or discuss ideas with the SCs or other visitors.

"I ask them if 'there is anything that interests you?' or conversely, they teach me. People who look at the whiteboard may have another question or have a completely different idea, saying, 'I'm interested in this.' We can have a different kind of dialogue from the exhibition floor."

Takeshita wants to tease out various ideas from visitors while respecting their opinions. Together with the other SCs, she is exploring multiple methods of dialogue.

Enjoying "gaps" and connecting research and society

"What do you think is the difference between androids and humans?" Hiromasa Mitsui, an SC, asks visitors looking at the android "Alter," and the dialogue begins. The visitors deepen their thinking about androids and intelligence.

Mitsui has been organizing an event where researchers and the general public can think together. It is about a "future society in which robots and other systems with intentions and desires will live together with humans." This is envisioned by the development project led by Professor Hiroshi Ishiguro, the developer of Alter. Researchers in not only engineering, but those in law, philosophy, and ethics participate in the event as well. Encouraging dialogue between researchers in different fields is one of the SCs' essential roles.

"In the session where we discussed what a robot is for Japanese people from the perspective of Japanese culture, there were quite a few differences of opinion even among researchers, such as when a philosophy and ethics professor refuted Prof. Ishiguro's opinion. We enjoy such 'gaps' among researchers in a good way."

As Mitsui was exposed to diverse opinions, he began to pay attention to society, not only science and technology. Connecting research and society is also an essential role of SCs.

"I would only think about research at university, but after coming to Miraikan, I realized how narrow my perspective was. I feel it is important to keep 'updating' myself every day," says Mitsui.

A being that brings awareness to researchers

SCs are now people that take researchers to "places of dialogue" and broaden their awareness.

Mitsui was involved in the planning of the online event "What's in the Oceans and Rivers? ― Water creatures and their connections probed by environmental DNA." In this program, the participating children collected environmental DNA (from organisms released into the environment such as oceans and rivers) beforehand. After classroom lectures and data sorting, the children interacted with researchers and SCs for about an hour to share the results.

"Because it was online, some researchers were worried that it would be too difficult or that it would be boring and painful."

Thinking they had a point, Mitsui discussed with the researchers and reached the idea of proceeding with the discussion by steps.

"We conducted the discussion in several stages: sorting out the data, choosing the data that interested the participants, and then thinking about that data. Halfway through, the researchers and SCs proactively talked to the participants, which helped convey the researchers' point of view, and helped the children actively participate in the discussion."

This experience also gave the participating researchers great awareness.

"I got a comment from them, 'Now we know designing a good process can enliven the discussion.' I was happy to know that they felt 'We can do it this way.'"

The attempts at creating co-creation

The spread of science and technology to date went with the successful development of new technologies, followed by implementation in society. However, an innovation "created together" by researchers and the general public, starting from social issues, will be required going forward. One of the attempts at creating such co-creation is the "Opinion Bank," planned and developed by Yuko Morita, Principal Investigator in Science Communication.

"It is a participatory exhibition that provides information on various topics and then asks visitors to answer related questions. We hope to use the collected opinions for surveys, research, and events associated with society and science."

One example of this system generating co-creation is the "In-body hospital" led by Innovation Center of Nanomedicine (Kawasaki City). The "In-body hospital" is a new medical technology that incorporates medicinal compounds into tiny molecular capsules to detect and treat abnormalities. The SCs devised a questionnaire to collect opinions on how to use this technology and got exciting results.

"The researchers thought it would be easier for patients if they could detect abnormalities in the body and treat them all at once. However, the general public's opinion was that even if something is wrong with them, they do not want treatment without knowing more about it. Instead, they want to consult with the doctor, and then decide, by thinking on their own. I think this was a case in which researchers were pleasantly surprised."

What is important is a relationship of trust

As a practitioner and researcher of science communication, Morita's recent matter of concern is that inaccurate information is more easily spread with the increased use of SNS.

"I feel that people tend to go further in the wrong direction if exposed to incorrect information first. People who can evaluate and sort out distributed information scientifically are highly required."

Morita continues, "The important thing to communicate information accurately is a relationship of trust."

"Even if the information is correct, if you don't trust the sender, you will become suspicious, thinking 'the information might have been manipulated." I hope that our SCs can earn trust resulting in visitors thinking, 'What this person says seems to be correct.'"

What skills are required to gain such trust? Morita says that you must first be able to determine if it is valid as science. Based on validity, it is necessary to sharpen the "social sensitivity" to predict a problem when it comes to contact with society.

Are there also hints other than in science?

However, Morita believes that even if each SC does not combine all of these abilities, they can play a role by working together.

"If one person is good at distinguishing scientific information, and another person has excellent dialogue skills, their working together may be a way to communicate science. We need the ability to express what we think is the problem in words or pictures, and encourage dialogue by saying, 'Why don't we think about it together?'"

Morita herself is working on a new activity to go beyond the conventional framework of science communication. One such activity is interacting with "liberal arts communicators," who communicate humanities research in an easy-to-understand manner and connect research and society.

"With the researcher at the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, we discussed expressions to prevent misinformation from being conveyed, and with the researcher at the National Museum of Japanese History, we planned a gender-themed event. You may also find hints on how to handle science information in places other than science, too. With advice from many people, I would like to compile knowledge on where we need to be careful in communicating science, with our SCs being aware of the same issues."

Asuka Takeshita

Science Communicator (SC) at Miraikan. Master's degree in Agriculture. Completed her studies at the Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University. After working as a civil servant in agricultural engineering, she became an SC in the spring of 2020.

Hiromasa Mitsui

Science Communicator (SC) at Miraikan. Ph.D. in Science. Completed his studies at the Graduate School of Advanced Science and Engineering, Waseda University. After working as a researcher at a university, he became an SC in the fall of 2018.

Yuko Morita

Principal Investigator in Science Communication at Miraikan. Ph.D. After working at the Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, the University of Tokyo as a research associate, at a pharmaceutical company, and at the Science and Education Center, Ochanomizu University, she started work at Miraikan in 2012.

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.