Despite remarkable medical advances, treatment and repair of impaired kidneys has been challenging, and no curative treatment other than kidney transplantation exists. Therefore, if symptoms worsen, the patient needs to continue receiving dialysis for the rest of his/her life, inevitably reducing the quality of life of the patient greatly. To combat this issue, Rege Nephro Co., Ltd. (Kyoto City, Kyoto Prefecture) aims to devise and practically apply a cell therapy of transplanting kidney progenitor cells, which can protect the kidneys. The company aims for the realization of regenerative medicine using human iPS cells, hoping to reduce the number of dialysis patients.

Pharmaceutical companies withdraw from practical applications despite demonstration of effect using model mice

The kidneys, which are two fist-sized organs in the body, function in filtering blood and excreting waste products and excess salt as urine. Impairment of this function is fatal as it leads to the accumulation of waste products in the body. However, no effective treatment other than kidney transplantation has been established. Moreover, in reality, the number of donors for kidney transplantation is overwhelmingly smaller than the number of patients. Therefore, many patients need to continue to receive dialysis for the rest of their lives. Currently, it has been estimated that there are approximately 340,000 dialysis patients in Japan and more than 13 million adults, or one in seven (of the Japanese population), are suffering from chronic kidney disease (CKD) and can potentially become dialysis patients.

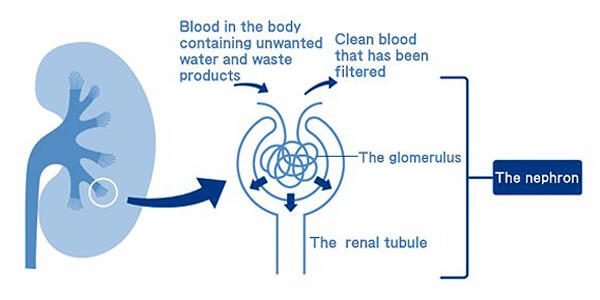

To improve this situation, Professor Kenji Osafune of the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application at Kyoto University is working on research for a treatment that prevents CKD deterioration. Regarding the commencement of his research, he says, "Many organs and tissues can regenerate themselves and return to their original state even when they develop disease or injury, but the kidneys do not. I became interested in this when I was a medical student." When Dr. Osafune was a medical student, research on regenerative medicine was not active, and reviving a damaged kidney was thought of as impossible. Although he had gained clinical experience as a nephrologist, he enrolled in the doctoral program at the School of Science, the University of Tokyo, in 2000, hoping to develop a treatment to help more patients. Then in 2006, he discovered for the first time in the world, nephron progenitor cells while investigating the process of kidney formation in mice during the fetal period. These cells can remove waste products from the blood into the kidneys (Fig. 1). However, even if the nephron progenitor cells could be obtained, culturing them into a kidney that could be transplanted into a patient was difficult because of the complex structure of the kidney.

After joining the iPS Cell Research Center at Kyoto University (current Center for iPS Cell Research and Application) in 2008, Dr. Osafune work ed on research involving transplanting nephron progenitor cells into the kidneys of CKD patients. During this time, he learned that cell therapy was being performed to transplant tissue stem cells to protect injured organs. Dr. Osafune recalls, "I thought that using this method as a reference, we could protect the kidneys by transplanting nephron progenitor cells created from iPS cells."

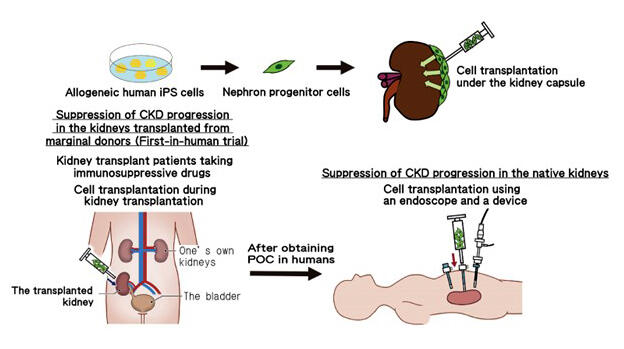

In 2015, he conducted an experiment using kidney disease model mice to transplant nephron progenitor cells under the renal capsule of the kidneys. It showed that nephron progenitor cells might better suppress the exacerbation of symptoms than the drugs used by CKD patients to protect their kidneys. While the detailed mechanism is still under investigation, the molecules secreted by nephron progenitor cells are thought to protect the kidneys and prevent kidney fibrosis, thereby suppressing the exacerbation of symptoms.

Thinking that nephron progenitor cells may prevent CKD deterioration in patients before they require dialysis treatment, he proceeded with joint research with a pharmaceutical company. However, no practical application could be obtained. With gratitude to the company, he says, "Pharmaceutical companies, which make a profit, usually have difficulty continuing their research unless it can reach a practical application in 2-3 years. Although our research was eventually withdrawn, the company had high expectations from nephron progenitor cell transplantation and stayed involved in the project for 6 years."

Entrepreneurship driven by enthusiasm with an eye towards clinical trials next year

Dr. Osafune continued seeking ways to turn his research into practical applications, believing that it would bring good news to patients with CKD. Then, he met Representative Director: Toshihiro Ishikiriyama through an acquaintance. Looking back on those days, Mr. Ishikiriyama, who had served as an executive in domestic and overseas pharmaceutical companies, says, "Not to mention the high level of technology, I was overwhelmed by his enthusiasm for patients. Until then, profits had been a priority, but I decided to take a chance with this research." After this meeting, Mr. Ishikiriyama and Dr. Osafune established Rege Nephro Co., Ltd. in September 2019.

It is essential to consider safety when establishing a treatment method. iPS cells are said to have a risk of tumorigenesis if a certain number of cells remain undifferentiated, but a safe virus has been developed for use in gene transfer without employing cancer-related genes. In addition, a unique technology that reliably induces differentiation in to the nephron progenitor cells has also been developed. Through establishing a method that does not cause side effects, they plan to conduct non-clinical safety test s in 2022 and begin a clinical trial with patients in 2023.

Dr. Osafune explains, "Because kidney function can be rapidly impaired due to a kidney transplant, we are initially trying to evaluate if nephron progenitor cell transplantation can protect the kidneys in patients who have had a kidney transplant." (Fig. 2) Rejection of nephron progenitor cells is unlikely since kidney transplant patients take immunosuppressive agents to suppress immune rejection. In addition, the kidneys are usually located deep in the lumbar region. However, since the transplanted kidneys are placed in the shallow part of the inguinal region, it is possible that nephron progenitor cells could be transplanted to the patients with less burden.

Strategic commercialization of results and securing stable profits

Conventionally, enormous costs have been incurred for culturing iPS cells into transplantable cells, but they have also developed a technology to produce a large amount of nephron progenitor cells. Katsuhisa Yamaguchi, Board Member and CFO, explains, "We have reduced the nephron progenitor cell transplantation cost to about 4 million yen per patient." The annual medical cost of dialysis is said to be approximately 4 million yen per patient, and if nephron progenitor cell transplantation could delay the start of dialysis by even 1 year, it will be well worth the cost.

However, it is easy to imagine that an enormous amount of money and time is needed for the practical application of such a treatment. Rege Nephro Co., Ltd. has successfully prepared kidney organoids, including the glomerulus and renal tubules, from nephron progenitor cells, and the company plans to pioneer their commercialization for drug development and pathological analyses. Mr. Yamaguchi says, "In a venture company, how we continue to raise funds is important. We aim to secure profits even with the results obtained in the course of the research via identifying their value and commercializing them."

Approximately 850 million CKD patients are present worldwide, and many await the establishment of an effective treatment for kidney disease in Japan and overseas. If a treatment is established using the iPS cell-derived nephron progenitor cells developed by Dr. Osafune, it will reduce not only the number of dialysis patients but also medical costs. The solid progress of these three individuals is about to change the world.