Associate Professor, Center for Environmental Remote Sensing, Chiba University

Principle Investigator for SATREPS since 2016

In recent years, extreme weather events due to climate change have cast a serious shadow over stable harvests of agricultural crops, but maintaining food security is one of the urgent issues that must be addressed if we are to continue supporting an ever-growing population and ensure that people can continue to enjoy an affluent lifestyle. The key is to build highly sustainable agricultural systems that can maintain production capacity. Associate Professor Chiharu Hongo of the Center for Environmental Remote Sensing, Chiba University, Japan, has established a remote sensing method for assessing damage to paddy rice, and is contributing to the stable operation and spread of the agricultural insurance system promoted by the Indonesian government.

Users are not increasing, even though the government is leading the way: speed and objectivity are the keys

It is expected that climate change will expose humanity to a variety of risks in the future. The Sixth Assessment Report, released by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in August 2021, lists the threat of "food security" as one of the major risks. Droughts, floods, and damage from pests and diseases that are caused by extreme weather not only damage crops, but they require significant labor and costs for restoring the farmland and planting the next crop. Many farmers with an unstable economic base could be forced to leave farming, which would further threaten food security.

It is expected that serious damage will be felt first and foremost in developing countries, and a variety of policies have been put in place. In Indonesia, where rice is the staple crop, a law on farmer protection and empowerment was enacted in 2013. Associate Professor Chiharu Hongo of the Center for Environmental Remote Sensing at Chiba University in Japan explained that "This led to the introduction of an agricultural insurance system under which the government pays compensation for damage to crops that is caused by droughts, floods, or damage from pests and diseases. There were pilot tests in several states, and it has been in full operation since 2016."

Dr. Hongo is a pioneer in the use of satellite data and drones to estimate and evaluate the condition of crops and fields. Currently, she is the Principal Investigator for the "Development and Implementation of New Damage Assessment Process in Agricultural Insurance as Adaptation to Climate Change for Food Security" (Figure 1) from the Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS), which is jointly operated by JST and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

Agricultural insurance has been improved in Japan since the enactment of the Agricultural Insurance Law in 1947. Dr. Hongo said that "Operations in Indonesia have just begun, and there is no shortage of challenges, but for those challenges we are using science and technology to improve the speed and objectivity of damage assessments." The current damage assessment method in Indonesia is to select three rice paddies from a vast agricultural land area of 200 to 300 rice paddies, visually observe 10 rice plants on the diagonal of the rice paddy for a total of 30 plants, and then calculate the average damage over the entire damaged area. Currently, no compensation is paid unless the damage is found to be 75% or more. Because this method of assessing the extent of the damage via visual observations yields inconsistent results, it is important to make objective assessments that the insurance enrollees can understand.

Dr. Hongo added that, "Speed is particularly important when operating an insurance program in Southeast Asia. The longer the examination process takes, the more time is needed to plant the next crop, which can lead to further losses. Indonesia has a rainy season and a dry season, and it is common for farmers to use double or triple cropping, planting two or three crops of rice per year on the same piece of land. Damaged rice paddies must be maintained in their current state until a damage assessor finishes their assessment, but the limited number of assessors limits the speed at which these assessments can be done. As a result, it takes time before compensation payments are finalized, which also highlights a systemic issue.

In addition, the concept of non-life insurance is not widely understood in the area, and the important of paying a small premium, often compared to the cost of a pack of cigarettes, to protect against future losses is not fully appreciated. For these reasons, there has not been a significant increase in the number of farmers using the state-sponsored insurance system. Dr. Hongo, a pioneer in introducing remote sensing technologies to agriculture, is working with IPB University in Bogor, Indonesia and others to establish damage assessment methods that meet Indonesia's needs and implement them into society (Figure 2).

The necessary conditions for smooth insurance operations: information gathering via satellites and drones

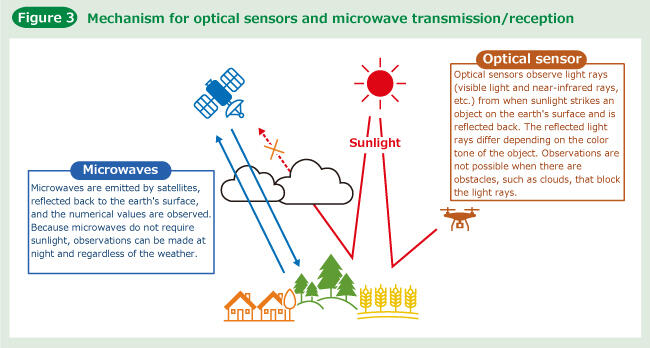

Remote sensing refers to technologies for observing objects from a distance by using sensors that are mounted on satellites and aircraft. Dr. Hongo and her colleagues plan to use optical sensors and microwave remote sensing to support the visual assessments by local damage assessors called pest observers (Figure 3). Specifically, the project will utilize observation data from low altitude drones and imaging from the Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 earth observation satellites.

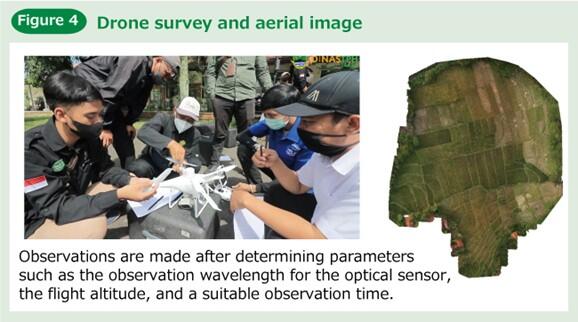

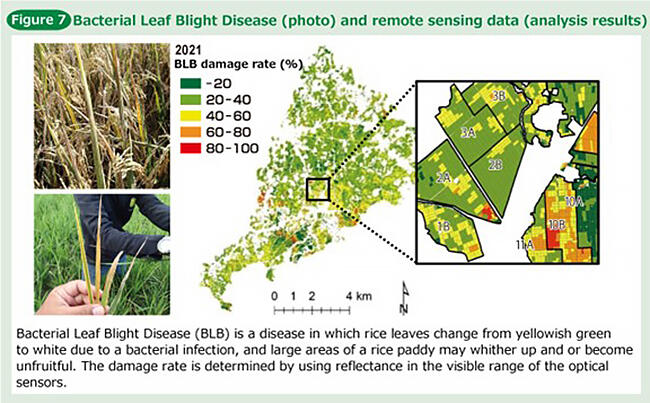

Drone imagery provides a quick view of a wide area of rice paddies while remaining at a fixed point (Figure 4). Drone imagery also improves the efficiency of pest observer patrols, which are conducted on a daily basis to check the growth of rice plants, and, furthermore, when any damage occurs the drone imagery is useful for understanding the overall picture. Optical sensors mounted on drones and satellites can detect differences in the color tone of growing rice plants and can be used as an indicator for knowing damage that has been caused by rice pests and diseases. Dr. Hongo and her colleagues are now working to realize damage assessments that cover an entire irrigation area of approx. 8,000 hectares, and first trying to look for Bacterial Leaf Blight Disease.

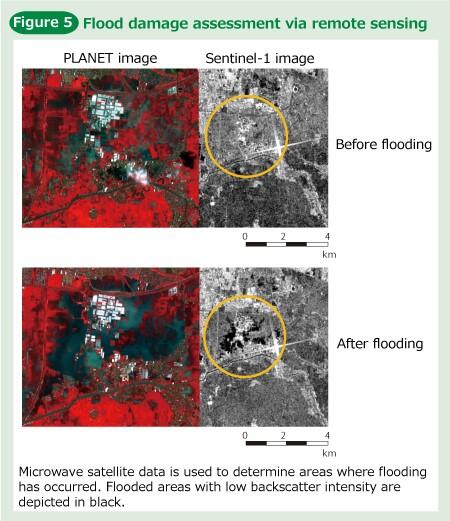

Furthermore, in addition to optical sensor data, microwave backscattering data is also acquired from satellites. Microwaves emitted by the satellite's radar bounce off objects when they hit them, and then the sensor captures the reflected microwaves. The strength of these reflections is called the backscatter strength, and there are differences between rice paddies where the rice has grown and rice paddies where the surface of the water is exposed. By acquiring this difference as image data, it is possible to assess flood damage (Figure 5).

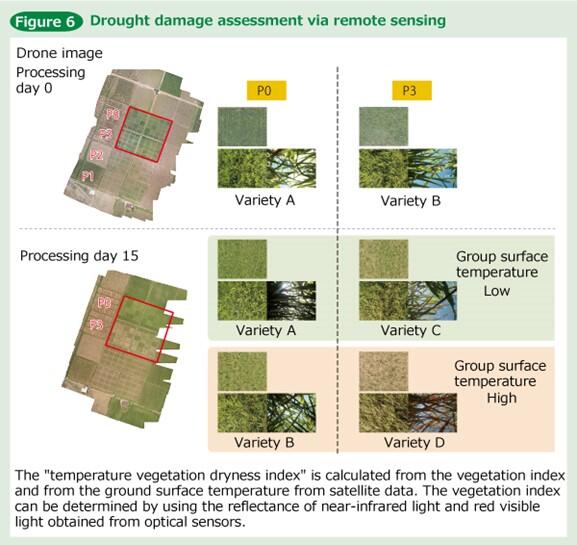

Additionally, based on the data obtained from the satellites, a temperature vegetation dryness index was calculated, which is widely used for determining how wet or dry the ground surface is. It was found that areas with a high index during the times when rice emerges have a high risk of drought damage (Figure 6). Dr. Hongo explained that "By statistically analyzing data obtained from drones and satellites and then applying it to models, we can investigate the various differences and changes in the ground surface." In doing so, they are trying to enable damage assessments in rice paddies for droughts, flood, and damage from pests and diseases (Figure 7).

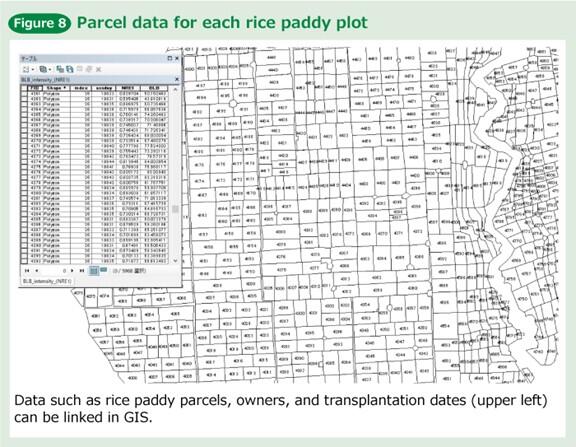

Furthermore, in addition to understanding the conditions of a variety of damage, transplantation dates are also essential pieces of information. "For example, when assessing flood damage, only rice paddies that are more than 30 days old from being transplanted are included in the damage assessments. Early-growth rice plants, that are less than 30 days old, are not surveyed because they will grow again once the water recedes. We are also aiming to identify transplantation dates via remote sensing." Unlike in Japan, where rice planting is done at the same time every year, in Indonesia, rice planting is done flexibly in each rice paddy according to the weather and irrigation conditions. While taking into account location conditions, remote sensing is being utilized to identify what data is needed to facilitate insurance operations (Figure 8).

At the same time, as part of the information infrastructure development, the project is also conducting research to incorporate detailed information on the target farmland into a digital map, such as rice paddy parcels, height differences, and the owners. By overlaying the data used for each type of damage assessments onto parcel data that is created in this way, it is possible to compile assessments for each rice paddy. The results of the project, will be made available to the pest observes and other related parties who are actually involved in damage assessments in Indonesia in the form of technical guidelines that outline the damage assessment methods and as a handbook that summarizes important matters related to the assessments.

Unexpected results from the COVID-19 Pandemic: easy access to voices in the field

In the latter half of the project, the plan had to be changed due to the COVID-19 outbreak, which has lasted for more than two years, but Dr. Hongo smiled and said that "happy miscalculations" continue to be made. "In assessing damage from diseases and insects, the pest observers and staff from the provincial government have learned how to acquire the data on their own. I didn't expect for them to grow so much." They are also expanding their own activities, such as by holding workshops on their own initiative and creating PR videos. Their activities have been favorably covered by the local media.

The project initially envisioned that the researchers would be responsible for the entire process, from data acquisition to analysis, and that the compiled damage assessments would then be handed over to the provincial government. However, in response to the enthusiastic reactions from the field, the use of automated data processing and easy-to-use applications, etc. let the researchers step back and have the field staff be responsible for the entire process themselves, from data acquisition to the production of damage assessment results. The researchers hope that, by building a system centered on technical support and clarifying the division of roles with the field staff, an independent and continuous operation will take root in the field. Dr. Hongo and her colleagues are motivated by the goal of establishing an organization to take over the SATREPS results at local universities and research institutions so that they can facilitate support.

The COVID-19 pandemic also led to an increase in online information exchanges, which has produced unexpected results. According to Dr. Hongo, "Previously, budgetary and business considerations limited the number of participants in meetings. However, with online conferences, it is now easy for the pest observers to participate. Compared with before, we now have many more opportunities to directly hear from the field." Even amidst the unforeseen circumstances of the pandemic, there was still a silver lining that boosted local morale.

Accumulating field surveys towards achieving results that fulfil needs

The aspirations of the local staff and the vibrant research environment are largely due to Dr. Hongo's long-held thoughts and practices. "The advantage of remote sensing technologies is that information can be obtained remotely. However, it is my belief that, unless you go into the field and work together with the people who will be using the technologies, that you cannot achieve a technology that will actually be used."

Just as she said, Dr. Hongo has been putting on her boots and entering the rice paddies with the local farmers and pest observers to try and understand the sites by using her own senses. Knowledge of a site allows for deeper interpretation of the acquired data, which in turn allows for the creation of methods that are adapted to the site. Dr. Hongo's actions surprised those around her.

In Indonesia professors do not go out and acquire data, and it is common for them to use a division of labor system in which specialized surveyors conduct the research. However, when Dr. Hongo, the project leader, went into the rice paddies herself and began the survey, all of the staff followed suit, regardless of their position.

While experiencing these cultural differences, Dr. Hongo says that the project has been able to proceed smoothly and without facing major difficulties thanks to the fact that she had made sufficient preparations before the SATREPS project began. The research and study in the field in Indonesia has actually spanned more than 10 years. In the beginning, she formed an observation team and traveled to Indonesia in time for the previous year's harvest season but experienced a setback because the rice paddy harvest was already over and only smoke, from the rice straw being burned, remained.

She reaffirmed the need for close communication with the local staff and then put it into practice, and that resulted in the proactive supply of information. The accumulation of trust has created the current attitude of working together as one. As for expectations and prospects, she stated that "The methods and technical guidelines we are producing are only for the FY22 edition. I hope to see more editions of the technical guidelines as technology advances and as society's needs change. I would like to see them developed and applied to different types of damages and crops. I want them to take on more and more challenges."

Insurance systems only function well when they are actively used by large numbers of policyholders. As such, achieving quick and objective damage assessments should be a major step in this direction. As a result, it is expected that this will lead to food security in Indonesia. There are many perspectives to learn from for developed countries that are seeking to realize a sustainable society, and future trends in the project will be paid attention to.

(Text: Mayumi Nishioka, Photos: Hideki Ishihara)