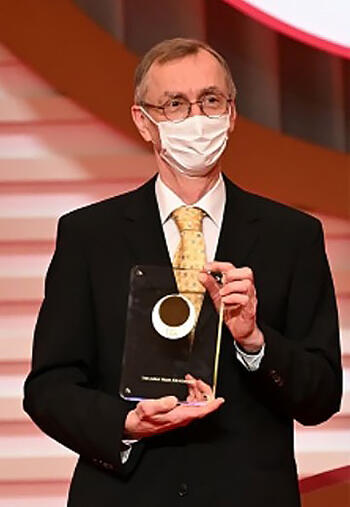

This year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Professor Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, who has made major contributions to research on the evolution of human species based on DNA analysis. He has analyzed the nuclear DNA of bone fragments of Neanderthals, a human species that went extinct around 40,000 years ago, in pursuit of the fundamental question of the origin of humans: "where did we come from?" This is a brilliant outcome that has shone light on our understanding of evolution.

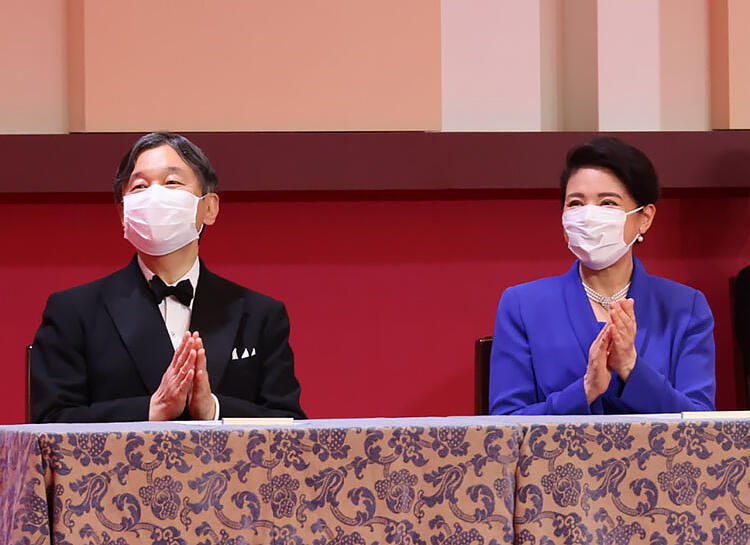

Professor Pääbo is also an adjunct professor at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) and visits Japanese research institutions such as Tohoku University and Kyoto University. In 2020, he was awarded the Japan Prize, and in April this year he expressed his thanks at the award ceremony, which was attended by the Emperor and Empress. This year, there were no Japanese winners of a Nobel Prize, but Professor Pääbo is a person with knowledge of Japan who has meaningful interactions with Japanese researchers. He is applauded by many researchers in Japan who are familiar with his friendly personality.

(Photo: Linda Vigilant ; Provided by the Nobel Foundation)

An interest in archeology from childhood

Svante Pääbo was born in Stockholm, Sweden, in April 1955, and is now 67 years old. He gained his doctorate in Uppsala University in Sweden, and in 1990 he became a professor of the University of Munich in Germany. He founded the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in 1997 and became its head. For around a quarter of a century after this, he has continued his research on the origins of human species and evolution.

"When I was a child, I wanted to be an archaeologist or an Egyptologist." Pääbo came to Japan in April this year to attend the award ceremony for the Japan Prize and gave this response in an interview with a representative of OIST, where he has worked as an adjunct professor since 2020. His interest in ancient people and modern people began when he was a child.

According to OIST, Pääbo, who became a researcher, made a unique attempt to extract DNA from Egyptian mummies, and later studied DNA analysis methods for ancient people at the University of California, Berkeley. His father won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1982 together with his colleagues "for their discoveries concerning prostaglandins and related biologically active substances." It seems that he has inherited his inquisitiveness from his father.

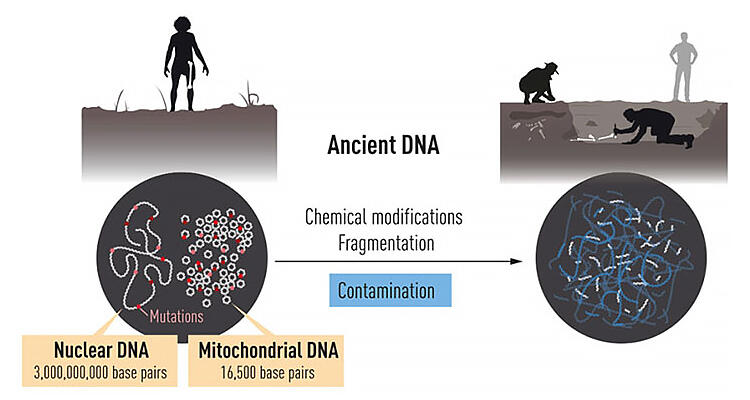

At the time, people did not think it was possible to carry out DNA analysis from the bones of ancient people. DNA degrades and fragments as time passes, so no-one could secure the amount required for analysis. However, Pääbo turned his attention to the PCR method, a DNA amplification technique that had only just been developed. Then, over a long time he thought he could obtain key information on human evolution from the DNA of bone fragments from ancient people.

(Provided by the Nobel Foundation)

Our ancestors and Neanderthals interbred

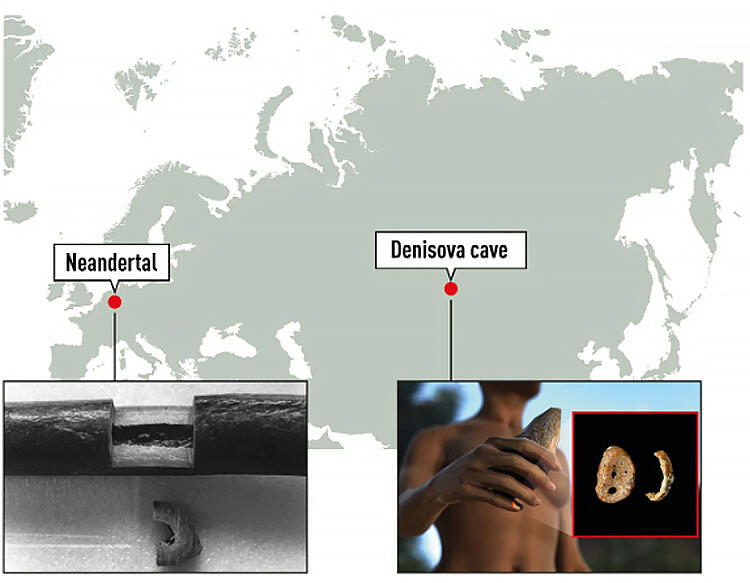

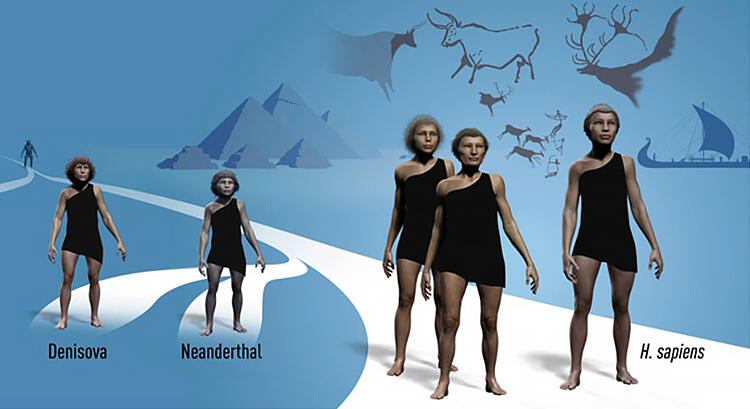

The prominent theory is that Neanderthals, an ancient human species, first emerged from Africa around 500,000 years ago. It is thought that they lived everywhere from Europe to the Near and Middle East for a long time after this, but went extinct around 40,000 years ago. Neanderthal bones were discovered in Germany in 1856.

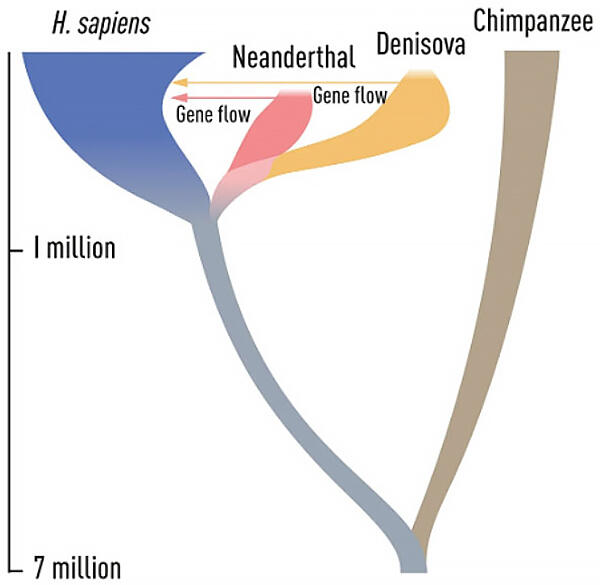

Professor Pääbo, who had sent away for some of these bones, first decided to sequence the mitochondrial DNA of organelles in cells. This is passed on from mother to child and is short, with around 16,500 base pairs, making it effective in the investigation of DNA. He determined the entire sequence in 1997. The outcomes of this made it clear that Neanderthals were not the direct ancestors of the modern human species Homo sapiens.

Professor Pääbo believed that he would not be able to pursue the evolution of modern humans just from these outcomes. In the 2000s, next-generation sequencers, which can determine DNA sequences in large quantities, came into being, so he focused on nuclear DNA analysis. Then, in 2010, he determined the entire sequence of around 3 billion base pairs.

From this ground-breaking analysis result, it became clear that between 1% and 4% of all the DNA of modern humans living in Europe and Asia is inherited from Neanderthals. Modern humans - our ancestors - interbred with Neanderthals.

His insatiable inquisitiveness continued after this. He turned his attention to a bone fragment excavated from Denisova Cave in Siberia, Russia, in 2008. He determined the whole nuclear DNA sequence, and, as this was an unknown species of human, he called them "Denisova." The results of comparing this to the nuclear DNA sequence of modern humans in different countries around the world showed that 4% to 6% of Melanesian and Southeast Asian DNA is inherited from Denisova.

(Provided by the Nobel Foundation)

(Provided by the Nobel Foundation)

Establishing paleogenomics and making major contributions to paleoanthropology

The Selection Committee of the Japan Prize Foundation, which decided to award Professor Pääbo the 2020 Japan Prize, gave the following explanation for this award. "The fact that Neanderthal DNA is present in modern humans, excluding the people of Africa (clarified by Professor Pääbo), illustrates a scenario of modern human migration in which 'the ancestors of modern humans who left Africa between 60,000 and 70,000 years ago are thought to have interbred with Neanderthals who already inhabited the Middle East around 60,000 years ago and spread around the world.'"

They praised his research results for "[revolutionizing] the paleoanthropological research of exploring 'the origins of modern humans.' His research methods and achievements have also significantly impacted all disciplines related to the study of modern human species, including anthropology, archaeology, and history, thereby contributing tremendously to the advancement of these disciplines."

The Karolinska Institute's reason for selecting him for the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was, naturally, the same as the reasoning behind his Japan Prize. In its reasoning, the Institute pointed out his far-sightedness, and praised his achievements in establishing paleogenomics as a new scientific field. It also noted expectations for future research and further outcomes with the ultimate aim of "exploring what makes us uniquely human."

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has often been awarded for fundamental research that will lead to an understanding of illness or the development of medicines, so awarding the Prize in the field of anthropology is exceptional. In a phone call with a representative of the Nobel Foundation immediately after the prizewinners were announced, Professor Pääbo said, "I have received a couple of prizes before, but I somehow did not think that this really would be...qualify for a Nobel Prize." He seemed very surprised at the information that he had been selected.

(Provided by the Nobel Foundation)

A visit to Japan in the spring to attend the Japan Prize award ceremony and more

Professor Pääbo has visited Japan many times before, but this year in particular he has made a lot of visits. He was chosen for the Japan Prize in 2020, but the award ceremony was postponed due to the spread of COVID-19. On April 13, when the pandemic had temporarily abated, an award ceremony was held for the eight prize winners from 2020 to 2022 at the Imperial Hotel in Chiyoda City, Tokyo, in the presence of the Emperor and Empress of Japan. Professor Pääbo was also present, in formal attire.

(Photo by/provided by the Japan Prize Foundation)

The Emperor made the following statement about Professor Pääbo's achievements. "Doctor Pääbo has successfully decoded the Neanderthal genome for the first time in the world by adopting a genetic method of extracting and analyzing DNA fragments from ancient human bones. His method has since yielded findings that have led us closer to the core of the evolution of modern humans and shed new light on the birth and evolution of the modern human species."

(Photo taken and provided by the Japan Prize Foundation)

Professor Pääbo came to Japan in February 2020 when the 2020 Japan Prize was announced, and spoke of his happiness at receiving the prize at a press conference: "I'm very honored. I feel that it has been acknowledged that I have opened a genetic window, and that research on the evolution of humans has advanced."

After attending the Japan Prize award ceremony in April this year, he flew to Okinawa Prefecture, where OIST is located. This was to participate in a seminar held there, and to give a lecture in front of students and faculty members. Since May 2020, Professor Pääbo has been the leader of the Human Evolutionary Genomics Unit at OIST, which boasts high education and research levels, with 80% of its students coming from overseas. While he is based in Germany, he sometimes visits OIST, continuing his research comparing modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisova.

(Provided by OIST)

"Our teacher has won" is the feeling among staff and students at OIST toward this year's Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. They say there was loud cheering from the students when they heard the news of who had won the Prize.

Deepening exchanges with Japanese researchers

OIST's President/CEO Peter Gruss made the following comments on the awarding of the prize: "All of OIST congratulates Svante Pääbo. I am very happy that he now wishes to compare the differences between Neanderthal and Homo sapiens genomes here at OIST."

In September 2020, after becoming an adjunct professor at OIST, Professor Pääbo published a paper in the science journal Nature. The paper clarified that modern humans have inherited genes associated with the risk of serious illness from COVID-19 infection from Neanderthals. There were various hypotheses at the start of the pandemic as to why there were less deaths among Japanese people than among Europeans and Americans. This paper explores the particular mechanism of infection among Japanese people.

Professor Pääbo's university connections are not to OIST alone. In September this year, he visited the city of Sendai, attending a seminar held by the Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization, Tohoku University, and gave a lecture there. This organization is well known for its ongoing research concerning a 150,000 strong Japanese genome cohort. Professor Pääbo observed the organization's facilities, and enthusiastically listened to their explanations. It seemed that he has a strong interest in their research content and techniques.

Moreover, Kyoto University often extends invitations to Professor Pääbo, so his exchanges with researchers from this university are also ongoing. He was awarded the Keio Medical Science prize in 2016. He is well known among the Japanese research community for the uniqueness of his research. The consensus among the people who know him in Japan is that: "He has a friendly personality. He is a person who knows about Japan and has deep knowledge of Japanese culture because of his profound exchanges with Japanese researchers."

(UCHIJO Yoshitaka: Science Journalist, Kyodo News Visiting Editorial Writer)

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.