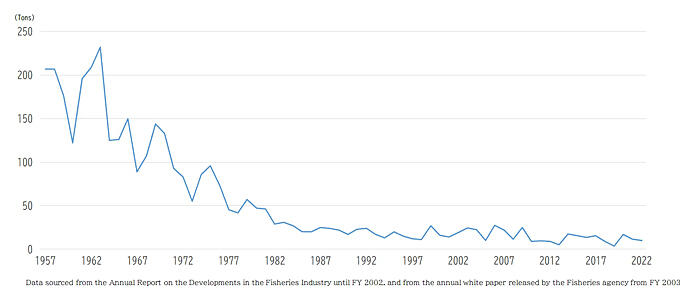

In recent years, the number of eels being caught has sharply decreased. Japanese eels are migratory fish that migrate south from Japan to spawn in the seamounts of the Mariana Trench, but due to human fishing and environmental degradation, the number of eels returning to Japan's rivers has been decreasing in recent times. This installment of "Youth in Tune with Nature," focuses on high school students who are working with researchers and local communities to protect and nurture eels, which are on the verge of extinction. This article will introduce two different approaches that are being pursued by two schools, each according to their lifestyle and environment: Denshukan High School in Fukuoka Prefecture, which seeks to create environments in which eels can easily live, and Miya Fisheries High School in Aichi Prefecture, which aims to achieve complete aquaculture of eels.

Conducting biological surveys through sinking ishikura kago into rivers

In Yanagawa, a castle town that still retains a strong atmosphere of the past, students from the Natural Science Club at Denshukan High School in Fukuoka Prefecture are working to restore the eel population. The town is lined with canals, and river cruises and eel-based cuisine are the main attractions for tourists. However, as the water supply system has been improved and as residents have stopped using the water from the canals, the water quality in the canals has gradually deteriorated. As a result, the populations of many aquatic animals, such as eels, have plummeted. In 2014, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed the Japanese eel as an endangered species, which prompted efforts to restore the population.

(Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries data)

Shinji Koba, the advisor for the Natural Science Club, said, "With the cooperation of Dr. Noritaka Mochioka from Kyushu University, we received permission from Fukuoka Prefecture to conduct a special harvest of juvenile eels, which are called 'shirasu unagi' in Japanese. Since then, we have caught shirasu unagi, raised them ourselves, and then released them into Yanagawa's canals and the nearby Iie River." Additionally, he also stated that, "We utilize a traditional method called 'ishikura kago.' In this method, an ishikura kago (stone-filled basket) is submerged in the river to create a hiding place for the eels. Crustaceans that serve as food for the eels also breed in the same place, and the river environment as a whole can be improved."

(provided by Denshukan High School)

Since 2015 when the school obtained permission, more than 10,000 shirasu unagi have already been caught and more than 9,700 eels have been released. Wire tags are attached to the released eels, and capture surveys are continuing in the Yanagawa canals and in the Iie River. The results have made it clear that the Iie River is a more suitable habitat for the eels.

(provided by Denshukan High School)

Fallen leaves from camphor trees reduce mortality

Mr. Koba has instructed the students in the club to take on new initiatives every year, and, in 2022, the third-year students conducted research on breeding environments for the eels. Natural Science Club President Souta Ohasi explained, "In the past, shirasu unagi raised on campus had a high mortality rate, and there were years when about 40% of the eels died. But, when some of the older students put fallen camphor tree leaves in the eel tanks, the shirasu unagi almost completely stopped dying, so now our year is investigating what made the fallen camphor tree leaves so helpful." According to Mr. Koba, he heard from a local fisherman that the oysters he farmed didn't get sick if he added mulch from the mountains, which led to the idea of adding fallen camphor tree leaves.

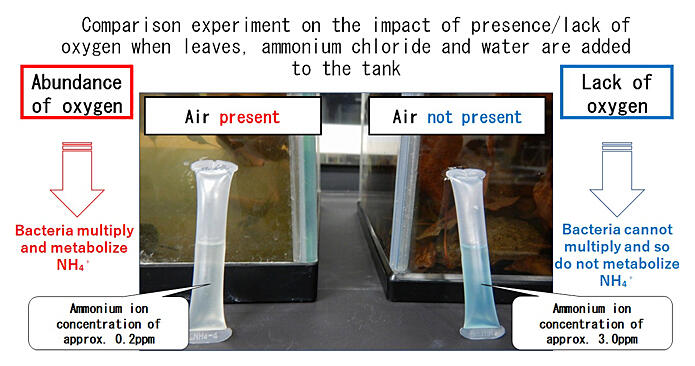

Souta and his team carefully investigated the differences from when fallen camphor tree leaves were present or absent, and the differences from when air was pumped into the water and when it was not. After analyzing the ion concentrations in the water, they concluded that bacteria attached to the fallen leaves directly took in ammonium ions derived from eel excretions, synthesized amino acids in the process of nitrogen assimilation, and multiplied, thereby suppressing the increase in ammonium ions, nitrites, and nitrate ions.

(provided by Denshukan High School and translated by Science Japan)

(provided by Denshukan High School and translated by Science Japan)

After seeing this result, the Yanagawa Eel Farming Association requested that its operators try eel cultivation using fallen camphor tree leaves, and the discovery has been well received, with the operators saying that it "helps in keeping the eel tanks clean."

A desire to increase water retention capacity of the mountains and eliminate barriers to upstream migration

The students have also focused on the many dams (weirs) that have been constructed along the Iie River. These dams play an important role in preventing the river from overflowing when the water level rises and in securing water for agriculture when there are shortages, but they may also be a barrier to the eels that are migrating up the river.

The students tried releasing eels downstream from where the ishikura kago were installed but were unable to recapture the eels. It is highly likely that the multiple dams between the release point and the ishikura kago are impeding the eels' movement.

(provided by Denshukan High School)

However, because the dams protect the livelihoods of local residents, the students could not simply ask for them to be removed. Miuta Momohara explained that, "Therefore, with the cooperation of the landowners on the mountain, we cleared the bamboo forest upstream of the Iie River and planted cherry trees and Japanese maples, which have high water retention capabilities, in order to increase the water retention capacity of the mountain. Subsequent surveys then confirmed that the birds had brought seeds into the forest and that broadleaf trees such as hackberry, fig, and camphor trees were growing."

If the mountain's water retention capacity increases then the risk of the river flooding will decrease, and the day may come when the movable dams will no longer be necessary. According to Yui Sakata, "I think that high school students alone are not enough to improve the river environment, and that we need cooperation from many people. I hope that the students coming after me will continue our activities, and that they will make good use of social media and other means to spread the word about the Natural Science Club."

Growing living things and making discoveries as high school students

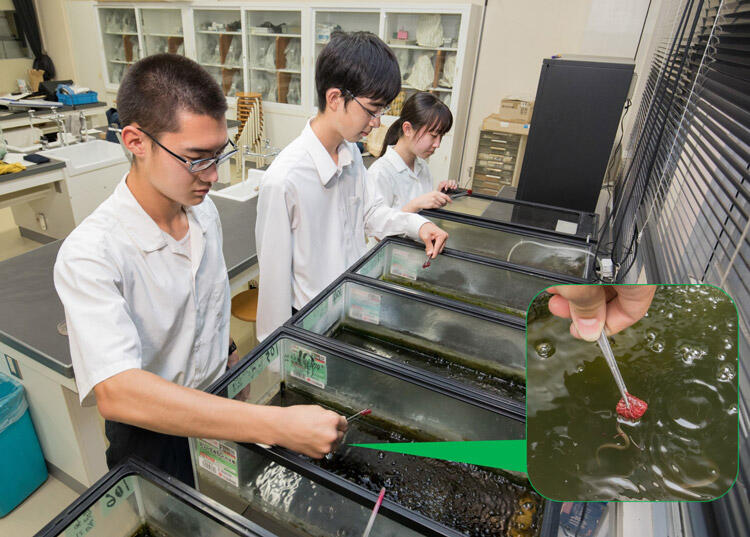

On the other hand, at Miya Fisheries High School in Aichi Prefecture, the students in the Marine Resources Department's eel team are aiming for complete eel aquaculture. In this course, the students learn aquaculture techniques through classroom lectures and hands-on practice from their first year in high school, and by their third year in high school are more involved in the development of advanced technologies. The eel team is one of the teams.

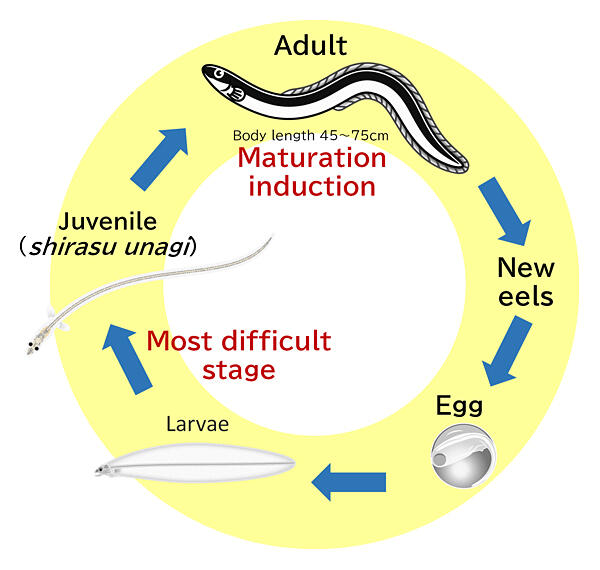

While general aquaculture involves obtaining natural shirasu unagi and then raising them until they are edible, in the complete aquaculture that the students are aiming for, the eels' whole life cycle will be brought under human control. In other words, fertilized eel eggs will be artificially hatched, the hatchlings will be raised from juvenile eels to adult eels, the sperm and eggs from mature males and females will be collected for artificial insemination, and the fertilized eggs will be artificially hatched again. Although the Fisheries Research Agency (now the Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency) achieved complete aquaculture in 2010, it has not yet been put into practical use.

Kiyokazu Kobayashi, a teacher at Miya Fisheries High School, said, "Aichi Prefecture is famous for eel farming, and our school has been involved in eel farming since the 1980s. So, when we heard that they had succeeded in the complete aquaculture of eels, we decided to take on the challenge as well. We wanted the students to have the same experience that their own parents had in raising them, to realize how difficult it is to raise a living creature, and to discover something in their own way through this process."

Hormone injections to promote female production and sex gland maturation

An important part of the complete aquaculture of eels is securing female parent eels. Although an eel's sex is not determined at the juvenile stage, more than 90% of farmed eels become male. Therefore, by mixing the female hormone estradiol in the bait, the eels are made 100% female.

However, because the eels do not reach sexual maturity when being artificially raised, the female eels are injected with salmon pituitary gland extract and an eel egg maturation-inducing hormone, while the male eels are injected with human chorionic gonadotropic hormone to stimulate maturation of their sex glands. Dressed in work clothes, the students remove the eels one by one from a bucket and skillfully provide the injections so as to minimize stress on the parent eels.

However, producing fertilizable eggs and active sperm is not easy. According to Mona Hashimoto, "The eels are injected with hormones once a week, but it is difficult to time the fertilization. Even if the females lay good eggs, they cannot be fertilized unless the sperm from the males is active, and it is difficult to produce good quality sperm and eggs."

Fertilized eggs increased due to an improved rearing environment and eel-derived hormones

Even after successful hatching, there is still a long road until they become adult eels. Researchers at the Fisheries Research Agency also conducted a series of trial-and-error experiments on the food given to eels immediately after they hatch, and succeeded in raising the eels after they were given eggs from the spiny dogfish, which lives in the deep sea. However, spiny dogfish are also rare and expensive, which makes commercial production difficult. Instead, the students use cheap zooplankton and a compound feed.

The survival record for the students' newly hatched baby eels is only 14 days, but Ren Ito said, "Our first goal is to surpass this record, and I hope that the younger students will aim even higher." Ayumi Kato also noted that, "I hope that the students next year can reduce the stress in captivity and raise parent eels that are healthy and energetic."

There are also bright spots in their work. Eito Baba explained, "Last year, the seniors were able to secure about 400 fertilized eggs from just one eel. As a result of increasing the overall number of brood eels, creating tubes in the tanks where the eels can hide, and administering eel-derived sex gland hormones, we were able to collect about 2,500 eggs from one eel this year, and I want the students coming after us to aim at collecting 10,000 eggs or more."

At both Denshukan High School and Miya Fisheries High School, the students' exploratory activities are gradually evolving, with knowledge and expertise being passed on from senior to junior students. The high school students who have tackled these issues have steadily increased their awareness of the problems they face, and they themselves are continuing to grow along with the results of their efforts.

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.