An academic field that spans the humanities and sciences and integrates the two is a symbol of a new era. This installment of Integration of Humanities and Science, in which interviews with researchers at the forefront of the field are posted, is titled "Historical Informatics." The goal is to digitize old documents and gain new knowledge that has was not available previously. Associate Professor Makoto Goto of the Research Department at the National Museum of Japanese History (NMJH) (Associate Professor of the School of Cultural and Social Studies, the Graduate University for Advanced Studies, SOKENDAI) has been working on historical informatics for more than 20 years and is a leader in the field. Science Portal interviewed him about the past and future of historical informatics.

(provided by Prof. Goto)

Creating the Shosoin document database

— What kind of research field is historical informatics?

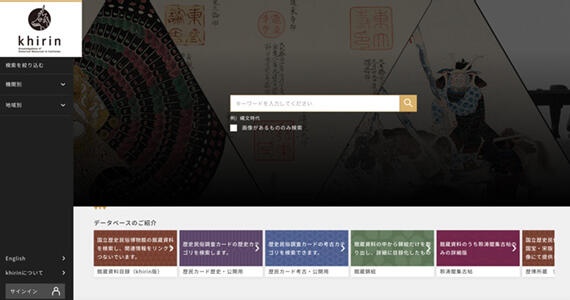

One example of the field is creating databases based on old documents written on paper. First, historical materials are stored in facilities, such as museums and archives, and are not easily accessible to everyone. Creating databases will make it easier for historians, experts in other fields and non‐experts, to use historical materials.

(owned by Naruto University of Education Library, photo provided by Prof. Goto)

—It is something like the historiographic version of open science. What kind of work is involved in creating a database of historical materials?

When working on the creation of the database of Shosoin documents, I first tagged and structured their textual data using XML (Extensible Markup Language). Moreover, I made it possible for a computer to correctly recognize the character information written on the paper. Various types of information related to the Shosoin documents are linked to them, enabling a comprehensive view on the computer screen.

(taken in 2014, provided by Prof. Goto)

— What are the Shosoin documents and why did you create a database of them?

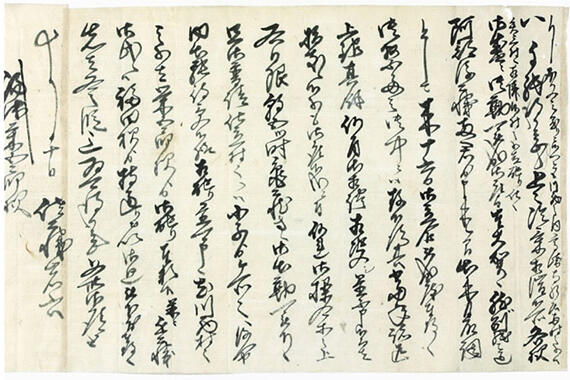

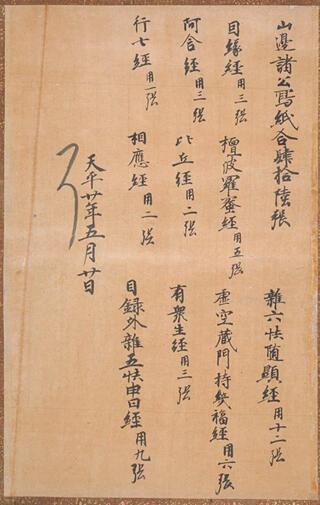

The Shosoin documents refer to the collection of documents that have been stored in the 'Shōsō‐in', or Treasure House, of the Todaiji Temple in Nara Prefecture. The contents of this collection cover a wide range of materials, including family registers, registers established for tax purposes (tax ledgers), and work reports from lower‐level bureaucrats, in addition to sutras copied at the Todaiji Temple. The collection contains 10,000 historical documents essential for studying old Japanese history. However, these are not in their original state. This was because paper was very precious in those days, and the back sides of documents that were no longer needed were reused. As a result, for example, the back of a family register has a government official's request for leave written on it.

To decipher the contents, it is necessary to perform "restoration" work during Shosoin document research, as represented by the Chinese characters "復原." However, the original documents are under the control of the Imperial Household Agency and cannot be viewed. Researchers use resources such as the "Shosoin Monjo Mokuroku (Inventory of the Shosoin Documents)," which is a record of original research, "Dai Nihon Komonjo (Old Documents of Japan)", which are print versions of the originals, and the "Shosoin komonjo eiin shusei" which are facsimile editions of the Shosoin documents. Although these documents have been cross‐checked and restored, they are difficult to handle, and research can be undeniably time‐consuming. Therefore, to leave the restoration to computers, we created a database of information from the Shosoin documents.

(owned by the National Museum of Japanese History, photo provided by Prof. Goto)

Potential to bring about breakthroughs

— Will the creation of a database of historical documents change the study of history?

Yes. A historical study and cooking are similar. Both begin with a search for materials. To cook, you must find good ingredients, and for a historical study, you must find materials that match your theme. Next, while cooking, we think about cooking methods that suit the ingredients, whereas in the study, we decipher historical materials. While cooking, the final finishing touches are seasoning and plating the prepared food. In a historical study, the seasoning is your own perspective and theory, while papers and conference presentations allow the material to be served to others.

All processes are essential, but you can rely on cooking appliances and computers. For example, there is a division of labor, where you use a food processor to chop ingredients, and you do the seasoning, which is the deciding factor in cooking. The same is true for a historical study, where the idea of historical informatics is to let machines do what they can do and devote more time to areas where the individuality of the researcher comes out. I believe that this may result in breakthroughs in the existing study of history.

— What inspired you to engage in historical informatics?

My original major was ancient Japanese history. When I was a high school student, I became interested in the study of history because I wanted to know the process leading to the present society. Thus, I thought I would learn from the old days in chronological order. The direct impetus came when I was in graduate school and heard from my informatics professor that information technology could be applied to the historical study. Because this sounded interesting, I began studying "digital humanities," which applies the informatics technique and technology to the humanities.

However, at that time in Japan, there were almost no examples of researchers in the humanities, including history, incorporating the knowledge of informatics. Therefore, it was possible that the significance of collaboration between the humanities and informatics may not always be understood by either group of researchers. About 20 years have passed since then, and research in digital humanities is progressing with the deepening of the mutual understanding of the possibilities and limitations of information technology, along with the significance and challenges of each academic field. I have been able to serve as an interpreter between the study of history and informatics, or as a catalyst for joint research.

"Thinking together" with the local people

— Dr. Goto, I heard that you are also working on the conservation of cultural assets such as old documents and ruins that lie dormant in various parts of Japan.

Yes. Things that should be passed on to the future as history and culture are not owned solely by museums and archives. They are also found in temples, shrines, and private homes such as old residences. These local historical materials are now in danger. They are being lost owing to natural disasters such as earthquakes and floods, and by changes in the heads of families. We are working to stem this tide.

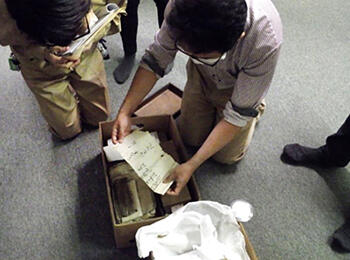

For example, when old documents are discovered during the rebuilding of a house owing to change in the head of a family, and the local board of education is consulted, my team at NMJH will work with them to conduct a joint investigation. After that, we consult with the local community to determine how to preserve and use the documents. After examining the actual items and getting a rough idea of the number and contents of the historical materials, we decide what to do with them. A request may be made to leave items related to the house in place with minimum conservation treatment. In other cases, we work together with local museums to organize and create a database of the historical materials brought to them. In any case, we are exploring the possibilities of using information technology to rescue and preserve local historical materials and pass on the culture.

(provided by Prof. Goto)

—Is the cooperation of local people essential?

Collaboration is important because it is the local people who will pass on the local history and culture to the future. We cannot preserve and pass on the local history and culture unless the entire local community is aware of and works together to protect the local historical materials, rather than just leaving this task to researchers.

The key to collaboration is for the thinking of the researchers and local people to be in agreement. A student who took my class once told me that a stone monument behind his house was in the digital archive. This stone monument may spark an interest in investigating local history and culture, leading to new discoveries. This is my goal when I refer to "thinking in agreement." I believe that the role of researchers is not to merely teach, but to support local people in preserving and passing on local historical materials as their own.

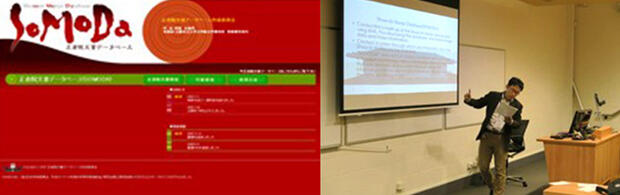

Furthermore, we are developing international collaborations, rather than merely limiting to regions in Japan. Last October, in addition to working on an exhibition of NMJH's collection at KU Leuven in Belgium, I conducted workshops and presented lectures on digital humanities. I plan to further promote activities based on historical materials and data.

(Right) "Collaborative exhibition work with people affiliated with the University of Leuven (KU)."

(both provided by Prof. Goto)

The need to collaborate in a wide range of fields.

—What kind of possibilities does the discipline of historical informatics have?

First, just as our mutual understanding of humanities, including the study of history, and informatics has progressed to mature digital humanities, I expect that collaboration between experts and non‐experts will progress to create new research fields.

Second, the progress in the digitization of local historical materials should enable digital humanities research that has not been possible previously. For example, there is an ancient document that records the rice harvests for a village over many years. By processing this information using a computer, we might understand the changes in the yield and environment. Moreover, historical materials may be applied to natural science. We need to collaborate in a wide range of fields.

Historical informatics has already used information technology to solve historical problems. In the future, some studies will use the study of history to solve informatics problems. For example, I believe that there is a possibility that a field will develop where "the study of history is used for informatics." For example, an AI might gain historical knowledge about social issues such as discrimination. Because the study of history is a study of society itself, I believe that its results should be returned to society.

Profile

GOTO Makoto

Associate Professor of the Research Department, the National Museum of Japanese History, and Associate Professor of School of Cultural and Social Studies, the Graduate University for Advanced Studies, SOKENDAI

Born in Fukuoka, Japan, in 1976. Graduated from the Department of History and Culture, Faculty of Letters, Okayama University in 1999. Received the JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists (DC2) in 2003. Completed the doctoral program in the Department of Philosophy and History, Graduate School of Literature and Human Sciences, Osaka City University, and received a doctorate (literature) in 2007. Received the JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists (PD) in the same year.

Became a Full‐time lecturer at the Faculty of Letters, Hanazono University in 2008. Following this he became a Visiting researcher at the Kyoto National Museum in 2012. Specially Appointed Assistant Professor, Head Office, National Institutes for the Humanities in 2014. Associate Professor, the National Museum of Japanese History from 2015 to the present. Started his current role as an Associate Professor of the School of Cultural and Social Studies, the Graduate University for Advanced Studies in 2019.

(ICHIJO Akie /science writer)

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.