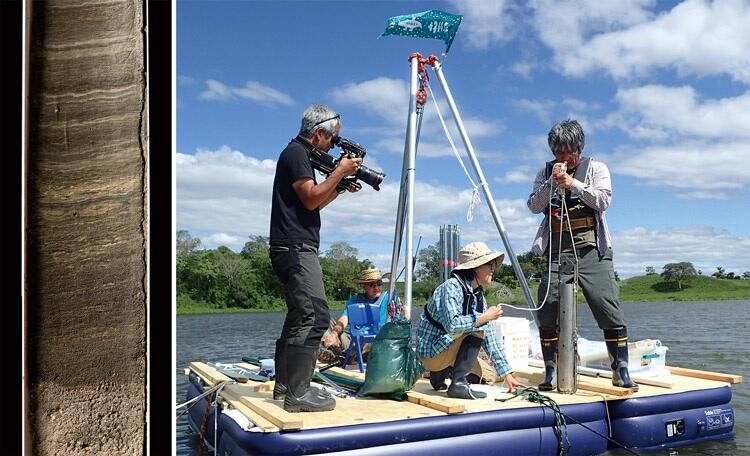

(right) provided by Kitaba, and collected varves (left)

In this final installment of the 'Treasures from under the ground,' we will introduce 'varves,' which are records of ancient history engraved in the ground. Varves are extremely difficult to find because they only form on lake bottoms under specific conditions. However, if collected, they may provide information on climate change over tens of thousands of years. Associate Professor Ikuko Kitaba of Ritsumeikan University (also Vice Director of the Research Centre for Palaeoclimatology at Ritsumeikan University) has been fascinated by varves resting on the bottom of lakes and has been working on collecting and analyzing them in Mexico and Guatemala.

Records of the distant past in the natural world

What did Earth look like and how did people live in ancient times? Many of us have probably wondered "If only I had a time machine…" at some point.

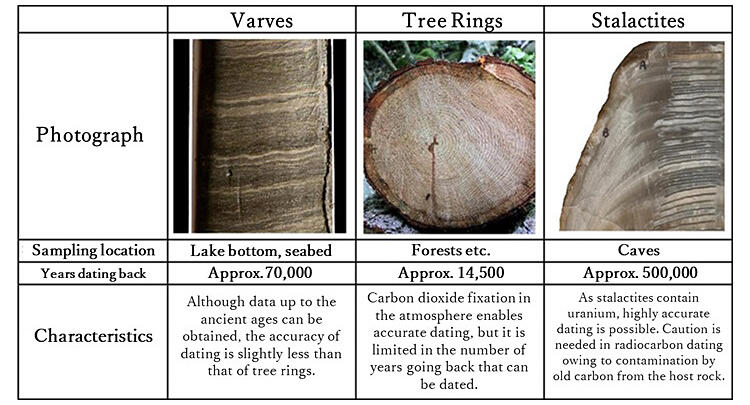

Various records of the distant past are left in the natural world, providing us with a fragmentary but informative glimpse into the world of the past. Tree rings are the most familiar. The degree of growth, which varies with the seasons, is reflected in the shade of color as the difference in cell density, and the rings usually increase one by one per year. One-year growth is also engraved in coral and fish otoliths. Although the cycles vary, growth lines on the shells and spines of cacti also indicate the passage of time. The same stripe pattern forms on ice sheets in Greenland and the Antarctic, owing to seasonal variations in the composition of snow that falls.

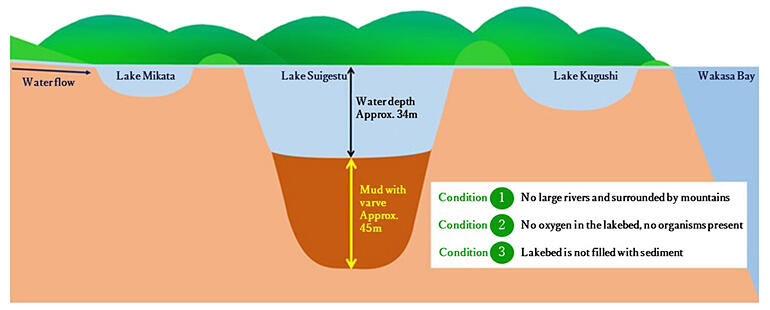

The stripe pattern that is formed on the bottom of lakes, which is highly accurate and can be used as a means to investigate the lives of people in some places, is called a 'varve.' The varves of Lake Suigetsu in Wakasa-cho, Fukui Prefecture can be traced back to approximately 70,000 years ago.

Stalactite image: courtesy of Professor Hai Cheng

Formed after clearing strict conditions

Then, where and how do 'varves' form?

Varves are formed by deposits of different types of materials at the bottom of lakes, depending on the season. In Japan, dark organic matter such as dead plankton accumulate from spring to autumn, while light-colored minerals accumulate from late autumn to winter. In this way, layers of stripe patterns are accumulated every year.

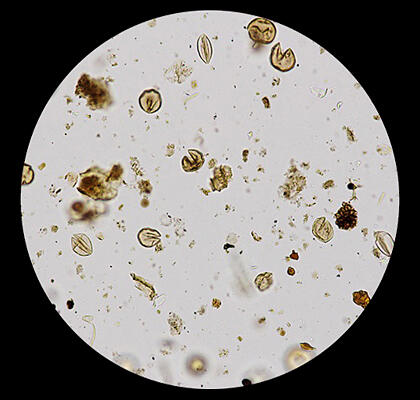

The thickness of one annual layer is usually less than one millimeter. However, they contain records of spring, summer, autumn, and winter. For example, if pollen is contained in a layer, the climate can be inferred from the plants that were growing there.

Provided by Nakagawa

However, if there is oxygen at the bottom of the lake, organisms in the area will disturb the sediments, resulting in no varve formation. Varves form only in deep lakes where the surrounding topography is not susceptible to heavy rains or strong winds and where the water is deep enough to prevent it from being stirred up by wind and rain.

The varves of Lake Suigetsu formed after clearing such strict conditions. This lake is surrounded by mountains and has continued to subside due to the influence of the surrounding faults. Therefore, varves from approximately 70,000 years ago to the present have been preserved. Incidentally, the person who played a central role in collecting and analyzing the varves of Lake Suigetsu was Professor Takeshi Nakagawa, who is now the Director of the Research Centre for Paleoclimatology at Ritsumeikan University, the same affiliation as Kitaba.

A 'measure' that will become the world standard for dating

Kitaba said, "The varves of Lake Suigetsu not only record past events but also serve as a global standard 'measure' for measuring the ages of various things around the world."

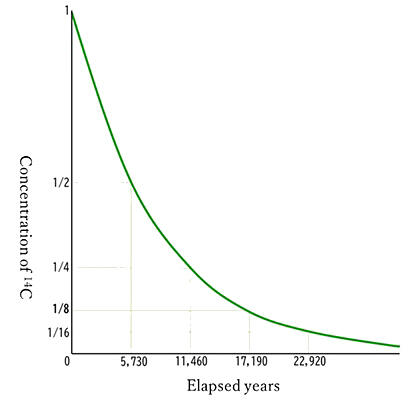

To determine the age of fossils and other materials, a method called 'radiocarbon dating' is used to measure the amount of radioactive carbon-14 (14C) in plants and animals. When cosmic rays hit nitrogen in the upper atmosphere, 14C is produced. Organisms take up 14C into their bodies, but when they die, the supply of 14C stops and gradually decreases. The fact the half-life of 14C is 5,730 years is used to estimate when the organism died.

However, since the amount of 14C differs depending on the era, a conversion table showing the amount of 14C from a certain number of years ago needs to be created.

Tree rings are used as a typical 'measure.' However, there is a limit to how far back trees can be traced; at present, this is approximately 14,500 years. Therefore, varves play an active role as a measure for the pasts when tree rings cannot be applied. Using varves, it is possible to go back even further than 50,000 years ago, when 14C is difficult to detect.

Exploring the factors behind the decline of the Mayan civilization

In fact, even the global standard 'measure' is subject to errors between the northern and southern hemispheres. In regions near the equator, there is an updraft region called the Intertropical Convergence Zone, which separates the atmospheres of the northern and southern hemispheres, resulting in an approximately 30-year lag in the variation of the amount of 14C.

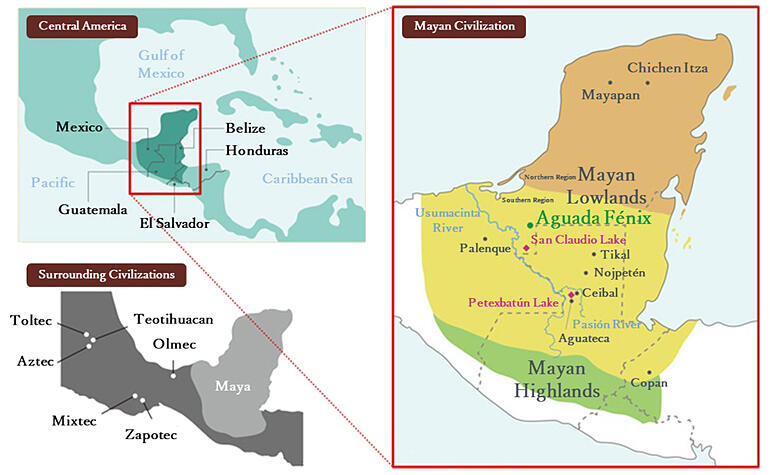

Additionally, in areas near the equator where there is little seasonal temperature change, trees often do not form distinct annual rings, and a different 'measure' is needed to understand the past more accurately. This includes southern Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, and El Salvador, where the Mayan civilization once flourished.

Provided by Kitaba and translated by Science Japan

The Maya civilization flourished for more than 2,000 years from approximately 3,000 years ago, and magnificent ruins that remind us of the past can be found throughout the region. They created a sophisticated calendar based on precise astronomical observations but were conquered by the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th to 17th centuries.

In fact, it is believed that the region had periods of both prosperity and decline since before that time. Around approximately the 9th century, many of the formerly prosperous cities were abandoned, and cities have since flourished in other areas.

So, why did people leave the cities where they lived? Various theories have been put forward, including the effects of war, deforestation, and climate change, but no conclusive evidence has been found.

It was here that the varves attracted attention for revealing the factors behind the decline of the Maya civilization. In this area, the rainy and dry seasons are clearly separated; a blackish layer with dead plankton and other materials in the rainy season and a whitish calcareous layer in the dry season are accumulated.

Attained after a great adventure

Kitaba joined the project in the Maya region when she was asked to analyze the varves found in Guatemala. She later became involved in the search for varves in southeastern Mexico.

However, the search was very difficult. Even if they aimed for the lake with the help of maps and aerial photos, there was no guarantee that there would be a road to get there. Negotiations with landowners were also necessary. Even after overcoming various obstacles and performing the excavation, dozens of failed attempts occurred because the area has many shallow lakes formed by changes in the course of the great river.

After two years of great adventure, they arrived at Laguna San Claudio (San Claudio Lake), located in the ruins of San Claudio, near the border with Guatemala. Kitaba and her team thought that they might be able to find varves in this lake, which is a depression lake formed by the denudation of limestone layers by groundwater. They made preparations for excavation and returned to the site the following year. What was dug out was mud in a striped pattern. They counted the number of stripes, matched the radiocarbon ages of the leaves contained therein, and confirmed that the mud was varve. This was completed in 2019.

Provided by Kitaba

In March 2020, a multinational San Claudio varve survey team conducted a full-scale excavation survey over a period of approximately two weeks and collected 6.5 meters of sediments in total length. Kitaba said, "The varves cover almost all periods of the rise and fall of the Maya civilization, and we are now able to investigate the climate changes experienced by the people who built the city in San Claudio."

Provided by Kitaba

People's lives are revived

An unexpected discovery was made while investigating the elements contained in the varves collected. They contained traces of excrement from the people who once lived here. Kitaba explained, "From these traces, we were able to determine when people lived around the lake. Circa 900 A.D., they seem to have abandoned the city at around the same time that other cities declined."

A closer examination of the elements in the varves also revealed that extreme weather events likely increased during the same period that people left the city. "The Maya people were able to adapt to a variety of climates, but I think that they were unable to cope with repeated extreme weather events in a short period of time, which may have led them to abandon their cities," she added.

"Right now, we are in the process of creating a 'measure' specific to the Maya region. When this is completed, the scenery that people saw in the past will come back to life, such as how many summers ago people experienced heavy droughts and heavy rains. The wonderful and endless charm of varves is where you can read such scenery," said Kitaba.

If a precise 'measure' unique to the Maya region is completed someday and climate change could be grasped on an annual basis or in more detail, the background of the rise and fall of the Maya civilization might become clearer. This could lead to the unraveling of the unsolved mysteries and, simultaneously, provide valuable knowledge to modern people facing climate change. The varves that Kitaba and her colleagues acquired — that is, 'treasures from under the ground' — have great potential.

Profile

KITABA Ikuko

Vice Director/Associate Professor, Research Centre for Palaeoclimatology, Ritsumeikan University.

PhD. in Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Kobe University in 2011. After working as a researcher and as an assistant professor at Kobe University's Research Center for Inland Seas, she assumed her current position in 2014, and has been vice director of the Centre since 2018.

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.