-

- Writer

- Mirai Horikita

-

- Interviewer

- Yūya Nishimura

-

- Editor

- Eriko Masamura

What is the difference between people who keep going until they succeed and people who give up along the way? For example, how do people become good at English? Apparently, it has to do with the development of a certain part of the brain. Chihiro Hosoda, a brain scientist and Associate Professor at Tohoku University, is studying the "ability to accomplish goals" from a brain science perspective and was the first in the world to prove that the brain changes when language skills are developed. What characteristics of the human brain give us an advantage in the age of AI? How does the ability to accomplish goals impact children? And what is the new system of parenting that Hosoda is looking into? Read on to find out…

Associate Professor, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Department of Brain Science, Tohoku University

Getting into brain science research to understand how the brain manipulates language

Dr. Hosoda, when did you first become interested in brain science? And could you tell us about what brought you into your current field of research?

I came into the field through Linguistics. The junior & senior high school I attended put a lot of effort into English education. We also had a sister school nearby, which was an international school. I often heard the students from there speaking English fluently on the train to school. They would suddenly switch over from Japanese to English in the middle of a conversation, or from English to Japanese, and I thought that it was wonderful.

I studied English literature at college with the simple desire to speak English well. When I had to decide the theme for my graduation research during my third year of college, I recalled how the international school students constantly switched languages. So, in order to learn what I have to do to speak English well, I decided to specialize in second language acquisition. In one of the lectures in that course, I learned about brain damage in bilingual people. The idea was that depending on which area of the brain was damaged, the injured person might retain only their first language, or only their second language. I'd always thought that language switching was great. But through my studies I learned that in some cases, it could, if anything, lead to loss of brain control.

It was then that I realized for the first time that it is the brain that controls language. As the theme of my graduation research, I decided on "Theory of Second Language Acquisition from the Brain's Perspective." My choice was based on the idea that if we can understand the mechanisms that control language in the brain, we can learn more effective ways of learning, and how to counteract poor conversational skills.

Since it is difficult to measure the brain in a liberal arts setting, I decided to pursue medicine in graduate school. At the time, Tokyo Medical and Dental University was presenting research on language using "Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)." Functional MRI can measure deep brain regions, so I decided to go to the Graduate School of Medicine there. That was the start of my career in brain science research.

(All illustrations and diagrams below provided by Dr. Hosoda.)

Nishimura: What an amazing transition from liberal arts to medicine! The culture must have been completely different, right?

Hosoda: It was totally different, but perhaps I was able to go into the field without any hesitation because I didn't have any preconceived notions of "what medical school and graduate school were like." In graduate school, I got to learn how to acquire data using large-scale equipment such as MRIs, so I'm glad I went into medicine, and I've enjoyed it.

Losing touch with the participants of the experiment triggered Dr. Hosoda's next research

Nishimura: What was the difference between your thoughts of English language learning before and after you conducted your research on it, and what were the new discoveries that you made?

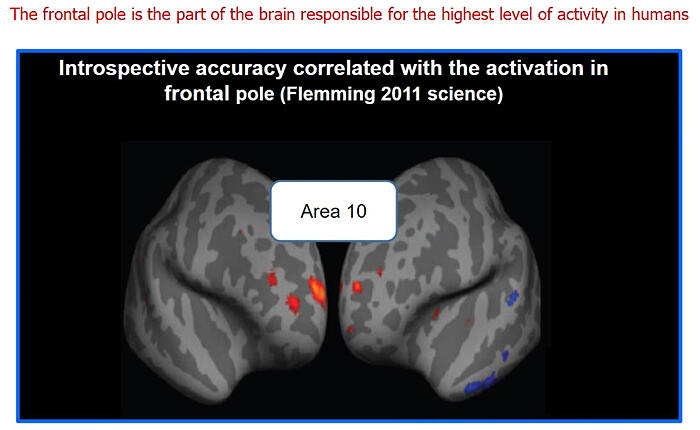

Hosoda: When I was in graduate school, I did an experiment where I asked students to do a long-term study task and took MRI images before and after they did it. There was a study published in Science where MRIs were taken before and after participants were given juggling training, but there hadn't been any studies in the field of cognitive neuroscience that addressed the topic of whether the brain changes before and after learning a language. It was very challenging for me, and although my boss at the time said, "I don't think it's going to work out," He agreed to let me go ahead with the project.

The experiment involved recruiting university students who couldn't speak English and having them study the language through an e-learning program. What happened next was something unexpected. A lot of students dropped out of the program along the way. We'd interviewed the students in advance and selected the ones who were highly motivated to learn. These were the ones who'd answered: "We definitely want to do our best." Even so, a lot of students didn't submit their daily homework, and then we lost contact with them. We were supposed to give the students weekly feedback based on their homework. Along with that, we were supposed to pay a participation fee to the students who just took MRIs and did not study. But we ended up sending emails every day to the students we hadn't heard from, asking, "How are you doing?" We'd tell them, "Please get in touch with us, so we can pay you the participation fee."

Maybe they didn't get back to us because they felt self-conscious, or guilty, about not being able to do the learning program. The professor told me that there wasn't much hope of success, but still, they gave me some funding to continue my experiment. Every time I opened my mailbox, I grew more impatient. We had been expecting that the results of the MRI would show no changes, but we never imagined that we'd lose contact with the participants.

Nishimura: So, there were a lot of students whom you couldn't get in touch with, even though you'd told them that you would pay them a participation fee.

Hosoda: Yes, that was a big surprise. Then it suddenly struck me, "There really are people like that." There are many people around us who are always late when we meet up with them, who never manage to keep their promises, or who run away before achieving their goals. So, even though we hadn't intended it, the experiment I just mentioned was taking data from people like that, who you find everywhere. We were getting brain data for them at the pre-learning stage. We thought it would be a good idea to compare this with the brains of the people who didn't drop out, which led to the following research.

Nishimura: It's interesting to see such real-world findings. How did the brains of the students who dropped out and those who made it to the end differ in the pre-learning stage?

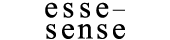

Hosoda: The degree of development of the frontal pole, a part of the frontal lobe that controls human intelligence, was different. This part of the brain is where you objectively evaluate yourself and think about where you are and what you need to do now in anticipation of the distant future. It is most developed in humans, and not so developed in animals. Animals also hunt prey and hibernate in anticipation of the future to some extent, but aren't humans the only beings that commit themselves to actions that may be of benefit 5 or 10 years later? Aiming to achieve goals while maintaining good self-control is very much higher-order behavior.

When the frontal pole is developed, you can objectively see what you can and cannot do now and the level of difficulty of a given task for yourself. That is what determines whether it's possible for people to continue learning or not.

Nishimura: Do you mean that when people said, "I'll participate in this program," or during the learning process, they had a lack of foresight?

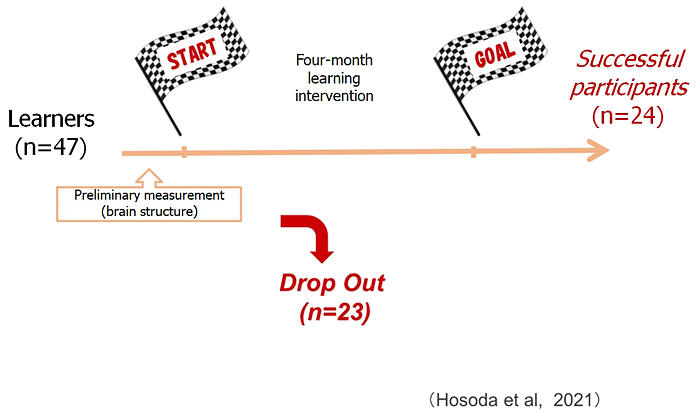

Hosoda: I absolutely believe that is the case. They may have overestimated their ability to do something when in fact they were unable to do it. During the experiment, I asked, "How well do you think you can handle this task?" It turned out that it was the people who'd overestimated their actual score that dropped out before completing the program. The data also show that the greater the difference between the people's estimated score and their actual results, the weaker their ability to continue was.

If you tweak the learning process, the frontal pole will develop and you won't drop out

Nishimura: Does the frontal pole develop depending on one's environment and behavior?

Hosoda: The brain itself is known to develop even after becoming an adult. Learning English will help your brain grow as your skills improve, even beyond the age of 20. So, what kind of tweaks are needed to develop the frontal pole in order to accomplish goals without giving up? For example, a classic method in education is to show small steps. When learners were given a sense of accomplishment each time, they completed one small goal, even students who thought they would be unable to keep going could achieve their goals. With this approach, when I looked at the brain again, the frontal pole was enlarged. On the other hand, students who were allowed to learn without taking small steps dropped out, and their frontal pole did not change.

It may be possible to use the state of the brain pre-learning to predict whether learning will continue. And if you set up a process whereby the brain develops, the brain will grow. A friend of mine recently told me that "women have a better ability to learn languages than men." Is there any difference in the development of the frontal pole between men and women?

Hosoda: So far, studies have shown no gender differences in the development of the frontal pole.

Horikita: I guess that the differences are individual, then. I believe that we'll be able to foresee the distant future as the use of AI advances going forward. When that happens, what kind of role will our human strengths, and the frontal pole, have to play?

Hosoda: I've never thought about it from that perspective before, but let's imagine that AI can predict to some extent where you will be in five years' time by inputting information about your current status, such as your current learning level, personality, and daily life patterns. If we could predict the future at a level that accurately informs us of our current status from moment to moment, we mightn't need part of the function of the frontal pole any longer. In other words, only the part responsible for working hard in the present while anticipating the future is no longer necessary.

There will be times when our forecasts are off, and if AI can take over the task of prediction completely, then we can use our brain for other things. But even if we had a constant flow of accurate predictions constantly telling us what we should be doing now, we'd still have to discipline ourselves and keep doing our best for whatever objective. So, it would be best if the parts of the brain we need to enable that were developed.

Nishimura: It's best if AI and people can create a good symbiotic relationship, right? Dr. Hosoda, what do you think about where this research will lead?

Hosoda: I initially thought that there would be different learning styles for each individual, and I tried to capture them using the findings of brain science and psychology. However, I realized that I was just thinking about how to change the path from a given starting point to a defined goal, and nothing more. It's certainly important for us to be able to do things that we couldn't do before, but recently I've been wondering if that is the only goal of education. Shouldn't we have diverse goals as well?

It's all very well to take a comprehensive approach of setting various goals and drawing pathways toward achieving them. But what I believe should come first is realizing the idea of "well-being through learning."

Nishimura: So, while you've discovered an effective learning method to some extent, it's not yet in its finished shape. Do you mean that you'll continue your research on "the ability to accomplish goals" as you've been doing up to now?

Hosoda: As long as we live with a goal in mind, everyone needs to have some degree of this ability, so that aspect of my research won't change. On the other hand, whether or not you have the ability to accomplish your goals is also related to whether or not you are able to set goals for yourself in the first place. I believe that what is needed is not being able to accomplish goals as a result of being given motivations or goals from above. Rather, the "ability to create your own goals" is more important than having the ability to accomplish them.

Nishimura: Up to now, the consensus has often been that the only way to do that is to recapture the internal motivation we had as children. I hope you can find a way to develop the ability to create motivation.

Creating a system to provide families with support from outside

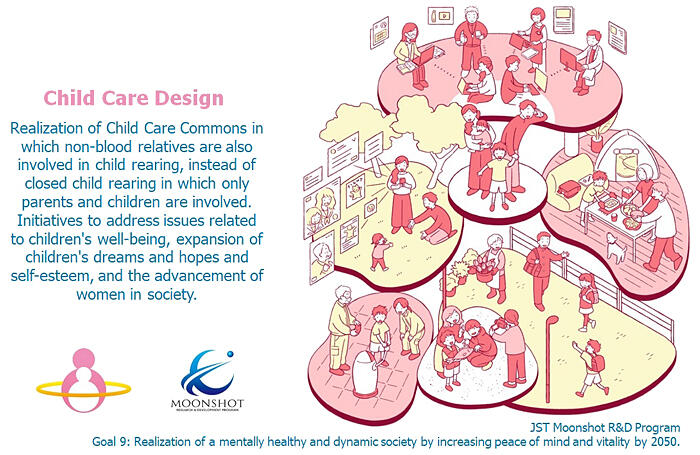

Hosoda: I think we have to find ways to create an environment that guides children to find their own goal. This may be the root cause of children's low levels of well-being through learning. What we're working on now is a project, under the Moonshot Research and Development Program, which aims to realize Child Care Commons, where society as a whole is involved in child-rearing. The burden of child-raising tends to be angled toward children's biological parents. The project is aimed at advocating a system that allows diverse people to be involved in a flexible and responsible manner through the identification of the requirements for such a system.

Nishimura: Why did you focus on the theme of child-rearing in the first place?

Hosoda: When I moved to Tohoku University in 2022, my children came with me. I was trying to figure out how to raise young children on my own while building a career in a place that was new to me. At that time, I learned that Moonshot Goal 9 aims for the "Realization of a mentally healthy and dynamic society by increasing peace of mind and vitality by 2050." One of the reasons for choosing this theme was that it matched my personal interests.

I mentioned earlier that the frontal pole can be changed and people's ability to accomplish goals can be strengthened. The participants in the experiment were young students, around 18 to 20 years old, and the only data we had on the way they'd lived their lives up until then was a snapshot of their brains at one point in time. So, I wanted to know how they'd lived till then and what kind of family environment they came from. It was also becoming apparent that a child's family environment affects their non-cognitive functioning and their well-being. That is the motivation behind the research aspect.

Learning happens at school, but genetics and the family environment have the main impact on a child's development. Genetics cannot be changed later, but the family environment can be accessed. Our research has also shown that children's ability to accomplish goals is correlated with their parent's ability to do so. So, I was interested in how the mental states of parents and children are related.

Although child-raising and education are often considered separately, it's probably wrong to separate the two. As a process that includes child-raising, I'm not sure that it's enough to look at how the influence of parents and the environment on the child over the long term plays out only in the context of conventional developmental psychology. I thought it was very important to have a comprehensive perspective on this issue, not only for children, but also for working mothers and the working generation at large.

Nishimura: It's amazing how parents get so worked up about choosing the right school for their kids, while leaving the family environment to take care of itself.

Hosoda: As well as that, the government's jurisdiction is also split between education and child-raising. There are some obvious guidelines for protecting children from abusive parents, such as "move the child to another caregiver by about age 3," but I think there are a lot of people who have problems with the parent-child relationship. There are many people who suffer from problems in their relationship with their parents, who are the closest people to them, even while they are living individual, independent lives. This affects their mental health, but few people go to the hospital because of parent-child relationship problems.

Rather than people with autism or learning disabilities, or patients with depression, I think I have to research people with problems that are not diagnosed as illnesses in the hospital, and that's exactly where problems in the parent-child relationship fit in. When children are brought up confined within the home, they face the barrier of not having a reliable adult around to help them if they rebel. I didn't realize this until I came to Tohoku, but there are still places with strong community ties. There are older people in these neighborhoods who people turn to for advice. This was the norm until not so long ago.

Of course, it would be an invasion of privacy if these older community residents started interfering by saying, "Young XX from that house over there is good friends with little YY," or, "Kid, please don't ever leave this town." So, I hope to take the good aspects of human relationships that Japan had in the past and adapt them to our modern sensibilities, and this can be achieved even remotely. I believe that increasing the number of trusting relationships while using digital platforms will help children achieve well-being. At the same time, I hope that the increased social capital that this generates will help alleviate mothers' worries and loneliness. This approach could achieve well-being for both parents and children, as well as for third parties involved with them.

Horikita: Many people associate the idea of alternative family structures with the way that LGBTQ families operate without spousal or gender roles, or with multiple family members living in a shared house and being involved in raising other people's children. Is your approach different from those ideas?

Hosoda: I think there is talk of the family becoming more diverse. That would be good, of course, but I myself am not thinking along the lines of extending family relationships outward. What I'm talking about is reducing the burden on the parents and making the child happy by having as many people as possible who know and care about the child involved in their development. I mean, you can't even ask your own parents to help raise your child if you don't trust them, can you?

I think that even though a third party may act like family, they'll be like family, but not family as such. It's not that I want third parties to get embedded in the family, but I would like to think about how we can create relationships in today's society where each person, including parents and children, can create a comfortable distance where each person cares a little about the other and people take care of each other, while also using digital technology.

If anything, I think it's very important that there is a society around the framework of the family, and that it is easy to go back and forth between the inside and outside of the family boundary. A system is needed to facilitate this back-and-forth, and one of the requirements for it is trust. If this system is realized, I believe it will lead to children themselves being happy, and women feeling that "they can have children" while staying active in society. It will also provide a place for the elderly.

But it has to be beneficial to the third parties who get involved. It needs to help people who live as parents and children normally, rather than "families where lots of people feed a child together." That's the very important and difficult part.

Analyzing questions that arise in one's own life, and seeking future solutions

Nishimura: The fact that you're researching this under the Moonshot Program rather than with an NPO means that the evidence is important, doesn't it?

Hosoda: Although I didn't mention it in my application for the Moonshot Program, I actually created a community of about 40 people at Tohoku University, where third parties, parents, and children interact together. It's been going very well, and the term "alternative relatives," which initially felt strange to us, has begun to feel less strange to us after about two years. Biological parents are the so-called "blood parents," but I think it's very important to have third parties who act as parents in society.

For example, if I'm away on a business trip and my child has a fever and I can't pick them up from school and take them to the hospital immediately, a third party can pick them up and take them home instead, without any formal procedures. There have been cases where adolescents who were unable to discuss their issues with their parents because they're going through puberty, get into a quarrel and get very depressed about it, but are able to open up to a trusted adult about their situation and have their issues resolved. There have also been situations where children's horizons were broadened by interacting with a third party, and they were inspired to develop a career path different from their parents.

So, we have gathered quite a few case studies as psychological data. It may be 5 or 10 years down the road, but we are thinking of systematically compiling the conditions required to make communities run well. We can then bring our findings to local governments, to reproduce these conditions.

Horikita: If this system works well, it could be used not only for child-rearing but also for nursing care. I suspect that many Japanese would have qualms about outside intervention by a third party who isn't related to them by blood. How does this compare with the situation overseas?

Hosoda: We've just begun comparisons with other countries, but there is data showing that Japanese people are less receptive to family diversity. The older the generation, in particular, the stronger the resistance. As for alternative families, more and more people in their 20s and 30s seem to be accepting them. But maybe the phrase "alternative relatives" wasn't the best choice.

Nishimura: Dr. Hosoda, your research is both in science and in the social sciences, isn't it? I'm very impressed by how you've done statistical processing and taken a further step to look at the natural phenomena.

Hosoda: The academic world has an established foundation, and it's really hard to find allies within that network and have them sympathize with and understand you. With the support of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), I've been able to make progress to some extent. Many researchers conduct research within their network of colleagues at their past laboratory or those in the same research discipline. My career path hasn't been very orthodox, and I feel it's difficult for someone like me to broach new ideas. I want to put my ideas into a form that will definitely make people take notice.

Nishimura: Indeed, you're quite right. As you train new undergraduate and graduate students, it's likely that a new field will emerge. You're involved in the field as an integral part of the process, rather than analyzing data after it comes in from the field.

Hosoda: There's probably a subconscious aspect to that. The questions I look at always arise out of my own life. Even while I'm researching a research paper regarding those questions, somewhere in the back of my mind I'm thinking, "Well, even so, we need to do something about it." That's what motivates me.

Nishimura: Do you enjoy going back and forth between the field and academia?

Hosoda: I live my life based on my personal interests, so there are many things I don't like about my work, but it is fun. I have experienced seeing that certain things are unworkable in the field and understanding the reasons for that in the academic framework. For example, in the context of my Moonshot research project, I'm both a parent and a woman, so I sometimes give my opinion on what the issues are and what is needed from that standpoint. But I often get responses such as, "That's a subjective view with no basis," or "We are not talking about such emotional issues." There may be some things that are not material for research papers and some stories that we should not seek evidence for, but I believe that we need to do better in terms of connecting research and social implementation.

A sense of "I'm not quite sure why, but..." is also an important key to humanity

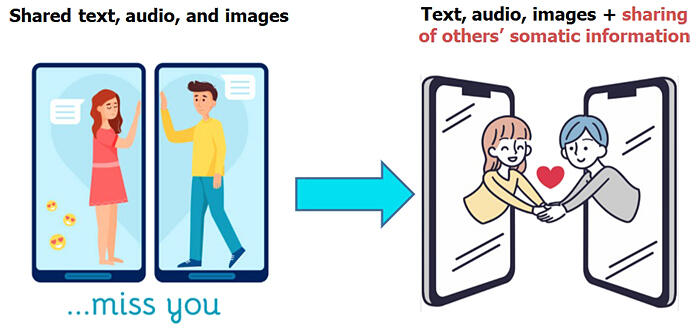

Nishimura: Yes, that's right. Another thing I'd like to ask is about your research on digital corporeality. You ask the question, "To what extent can corporeality be extended through the sharing of somatic information between individuals?" It's interesting to see how a brain processes other people's experiences and their own. In some cases, we may be able to amplify or decentralize our experiences. Why did you decide to research this?

Hosoda: The sharing of somatic information between individuals appears to cause an expansion of the sense of self, in which the experiences and sensations of others are taken as one's own. How will human emotions and decision-making change as these technologies develop? Our lab explores the impact at the individual level in a digital somatic society from a brain science and neuroscientific perspective.

It all started with Professor Yoshihiro Tanaka of Nagoya Institute of Technology. He was in JST's Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology (PRESTO) program at the same time as me. He approached me and said, "You're very interested in the relationship between individual differences in tactile perception and the brain, aren't you?" I was researching individual differences in the brain at the time. Now, we're experimenting to see what happens when we have a shared sensation of the other person touching us or shaking hands with us via the screen when communicating remotely. Experiments that involve implanting tactile information (sensations) experienced by others are still in their infancy. There will surely be individual differences, and we are in the process of seeing how the brain and behavior will change once sensations are shared.

Nishimura: What's the difference between handling tactile information and visual information such as text?

Hosoda: I think it's easier to evoke effects such as pleasure and discomfort. It's nice to be touched by someone you like, but it's very unpleasant to be touched by someone you dislike, isn't it? It's especially interesting to figure it out because these feelings depend on the person's emotional state.

Nishimura: Do you mean that the brain perceives the tactile experiences it feels pleasant or unpleasant differently, even if the intensity is the same?

Hosoda: Yes. Although there are engineers who reproduce the sense of touch, the changes in the brain caused by the experience of the person being touched haven't really been researched.

Nishimura: I think that as the relationship between learning and the brain and the relationship between the body and the brain become clearer, we'll achieve better resolution on human−social interactions and human-environmental interactions. In this way, through brain science, we may come to understand the meaning of cultural mechanisms that haven't received much attention before. For example, I think that festivals and oral traditions remain with us because they held meaning, though we're not sure what it is.

Hosoda: Festivals are a great example of practices that remain with us even though we don't understand why they're there, perhaps there is some kind of local god in the area, people do ground-breaking ceremonies, and the like. I think those practices have remained as a kind of local connection that is unique to Japan. Though nowadays, I feel that the connection has faded away, and only the event remains.

So, if people today who value time efficiency and cost performance do not feel the significance of a festival itself, I think the process of discussing it based on scientific evidence is key. On the other hand, there's also an important virtue in thinking "I'm not quite sure why, but I want to cherish this," and "I'm not quite sure why, but I think it's beautiful." If we have to explain everything theoretically to understand it, then we end up no different from robots. So, I guess that cultural things, in particular, can be handed down in a somewhat vague, undefined way. A sense of being able to have these feelings in an ambiguous way might be necessary to maintain our humanity and nurture what is important to us.

Nishimura: What we know is easy to quantify and explain, but what we don't know may be just as important, right? Dr. Hosoda, your research extends from English language learning to the ability to accomplish goals, and then to a slightly broader scope, addressing not only interpersonal issues but also the environment in which various people are involved in child-rearing, and even somatic information. But I think one of your basic foundations is to always go back to brain science.

I feel that it is unrealistic to apply brain science to the clarification of everyday events instead of special situations. I felt again that people who aspire to this kind of research may well belong to the next generation.

The idea that the more people don't properly understand their own abilities, the more likely they are to end up quitting makes a lot of sense from a business perspective. We have all seen that people who are overconfident in a job are less able to accurately estimate the number of man hours and processes required and end up making mistakes in estimating the schedule. We might have a vague sense that "the more prideful people are, the more slowly they develop." Dr. Hosoda has explained this from a brain-science perspective and her work will be a useful reference in exploring solutions going forward.

We may have an image of brain science as being concerned with how to develop memory and how that relates to lifestyle. Learning that the brain also controls the motivation to learn and work, and that correct behavioral changes can help us to accomplish goals even in adulthood, will encourage not only students but also many businesspeople.

Profile

Chihiro Hosoda

Associate Professor, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Department of Brain Science, Tohoku University

Graduated with a B.A. in English and American Literature from Tokyo Woman's Christian University in 2004. Completed a doctoral program at the Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences at Tokyo Medical and Dental University in 2010. (PhD in Medicine). In 2010, she joined the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry as a part-time researcher, then in 2012, she became a full-time researcher at the Advanced Telecommunications Research Institute International (ATR). In 2014, Dr. Hosoda became a specially appointed researcher at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Tokyo, and a Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) PRESTO researcher. Since April 2022, she has been an Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Information Sciences and at the Institute of Development, Aging, and Cancer at Tohoku University.

She is a Project Manager as part of JST's "Moonshot Research and Development Program Goal 9," which promotes challenging R&D based on bold ideas aimed at creating disruptive innovations. She is also a member of the Sendai City Educational Bureau's Learning Collaboration Promotion Office. Committee Member of Japan Human Brain Mapping Society Editorial board member of Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience. Administrative guidance committee member, National University Elementary School

This article was produced in cooperation with the Moonshot Research and Development Project Division of JST.

https://www.jst.go.jp/moonshot/en/index.html

Original article provided by esse-sense and translated by Science Japan.