"Where did the ancestors of the Japanese come from"? The answer to this romantic question has been the "dual structure model," which assumes that Japanese ancestors consisted of a mixture of the Jomon people and the Yayoi people, who were immigrants from the continent. This assumption has long been accepted almost as dogma. In this field, research using technology to analyze genomes (whole genetic information) in Japanese has flourished, and studies in recent years are revising this theory.

In April, a research group led by RIKEN and other institutions reported the results of analyzing the genomes of more than 3,000 Japanese people, revealing that the Japanese population is likely to have originated from three ancestral groups. Separately from this study, a research group led by Kanazawa University and other institutions has proposed a "tripartite structure model" based on genome analysis of human skeletal remains excavated from archaeological sites, showing that "modern Japanese originated from three ancestral groups of immigrants from the continent."

The RIKEN group's "triancestral origins" theory shares part of the concept with the "tripartite structure model" and challenges the conventional "dual structure model." With DNA and genome analysis techniques as powerful tools, evolutionary anthropology exploring the ancestry of the Japanese has revealed the complex process of immigration from one continent to modern Japan. Moving forward, more detailed information about our roots will be revealed. This leads us to the answer to the grand theme of inquiry, "What is our true nature?"

Provided by RIKEN

Ancestry is divided into three groups: "Jomon," "Kansai," and "Tohoku"

Mitochondria, which are inherited from mother to child, contain a small amount of DNA (mitochondrial DNA), which can be analyzed to determine maternal kinship for the identification of genetic roots. Half of the nuclear DNA in the cells of a child is acquired from the mother and other half is acquired from the father. Therefore, analysis of DNA sequences and mutation scales can be used to study human admixture, interaction, and migration.

The "triancestral origins" theory was presented by Team Leader Chikashi Terao and Senior Scientist Xiaoxi Liu of the Laboratory for Statistical and Translational Genetics, RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences, and Professor Koichi Matsuda of the Human Genome Center, Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo. Terao also served as the Director of Immunology Research at the Shizuoka General Hospital and as a professor at the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Shizuoka. The Shizuoka General Hospital and the University of Shizuoka participated in the study.

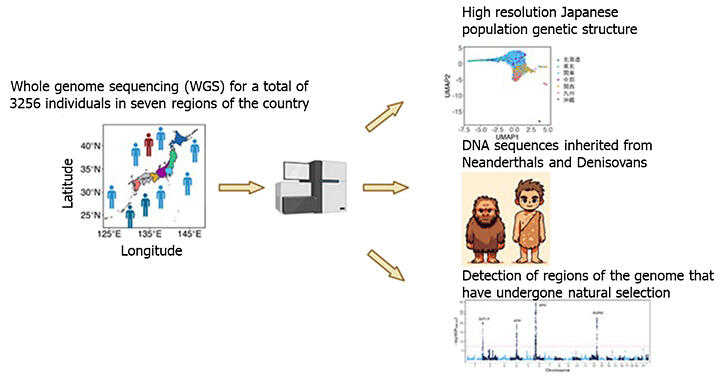

Terao and his colleagues used "Biobank Japan," an organization that collects and stores the blood samples and genetic information of many people. The research team continued the enormous task of characterizing the genomes by performing a detailed analysis of the complete DNA sequences of 3256 Japanese individuals registered at medical institutions in seven regions (Hokkaido, Tohoku, Kanto, Chubu, Kansai, Kyushu, and Okinawa).

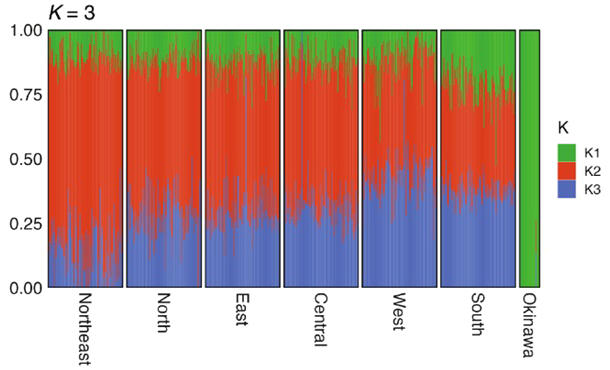

The results showed that the ancestors of the Japanese can be divided into three major main groups: the "Jomon" group, which is most commonly found in Okinawa Prefecture; the "Kansai" group, which is most commonly found in the Kansai region; and the "Tohoku" group, which is most commonly found in the Tohoku region. Further investigation was conducted on the percentage of genetic information of Jomon ancestry (ancestry ratio). It was highest at 28.5% in Okinawa Prefecture, followed by 18.9% in Tohoku and the lowest at 13.4% in Kansai.

Questioning the "dual structure model"

These ancestry ratios are consistent with previous studies that revealed a high genetic affinity between the Jomon and Okinawan people and indicate a high genetic affinity between the Kansai region and Han Chinese. People in the Tohoku region also had a high genetic affinity with the Jomon people and were close to the ancient Japanese of Miyako Island, Okinawa Prefecture, and the ancient Koreans around the time of the Three Kingdoms period (4th−5th century) in Korea.

These findings cast doubt on the "dual structure model," which assumes that the modern Japanese were formed by the admixture of hunter-gatherer people from the Jomon period and rice-farming immigrants from continental northeast Asia during the Yayoi period.

The ancestors of modern humans are believed to have interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans. A series of genome analyses have also identified DNA sequences that appear to have been inherited by modern Japanese from Neanderthals and Denisovans. Interestingly, the sequences inherited from the Denisovans included those related to type 2 diabetes. DNA analysis is also expected to reveal "disease susceptibility" and pave the way for personalized medicine. Further detailed analysis is awaited. The research paper was published in the American scientific journal Science Advances on April 17.

Provided by RIKEN

Provided by RIKEN

"Tripartite structure model" proposed based on genome analysis of human remains

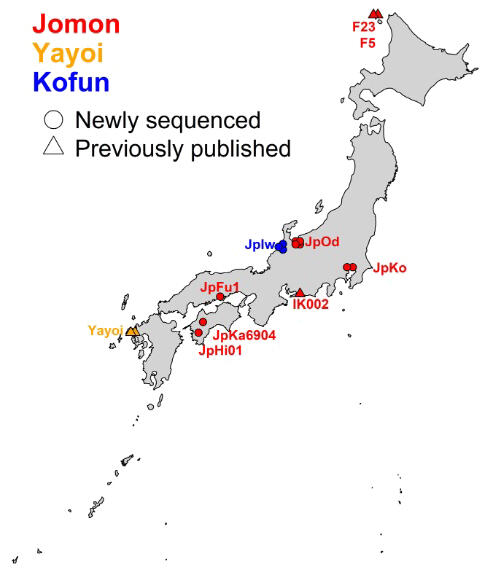

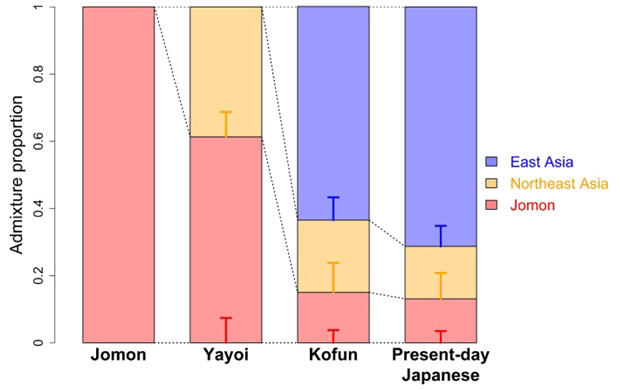

In September 2021, before the publication was released by the RIKEN led research group, a joint research group led by Kanazawa University and other institutions analyzed the genomes of human remains excavated from the Jomon, Yayoi, and Kofun period archeological sites. These results, showing that the modern Japanese have three groups of ancestors who immigrated from the continent were also published in Science Advances.

Many scientists participated in this joint research group, including Assistant Professor Takashi Gakuhari and Visiting Researcher Shigeki Nakagome of the Center for Ancient Civilizations and Cultural Resources (department name at the time of the research), College of Human and Social Sciences at Kanazawa University; Professor Daniel Bradley of Trinity College Dublin, Ireland; Assistant Professor Kenji Okazaki of Tottori University; Professor Naoto Tomioka of Okayama University of Science; and Director Kenji Kasai of the Toyama Prefectural Center for Archeological Operations.

Gakuhari and his colleagues obtained and analyzed the genomes of a total of 12 individuals from human skeletal remains excavated from six archeological sites: Kamikuroiwa Iwakage Ruins (Kumakogen Town, Ehime Prefecture), which dates to the initial Jomon Period; the Odake Shell Midden (Toyama City) and Funagura Shell Midden (Kurashiki City, Okayama Prefecture), which date to the early Jomon Period; the Kosaku Shell Midden (Funabashi City, Chiba Prefecture) and Hirajo Shell Midden (Ainan City, Ehime Prefecture), which date to the late Jomon Period; and the Iwade Horizontal Cave Tombs (Kanazawa City), which dates to the late Kofun Period.

The results were then compared to genomes reported with human skeletal remains excavated from other archaeological sites in Japan and the continent. The results indicate that the Jomon ancestral group split off from the continental population (basal population) 20,000−15,000 years ago and migrated to Japan, forming a small group of about 1,000 people. Based on these results, groups originating from Northeast Asia and East Asia presumably came to Japan during the Yayoi and Kofun periods, respectively, and formed admixed populations at each time.

The findings of this study suggest that influxes of genetically distinct populations from the continent to Japan took place in two stages in the period up to the Kofun period during which Jomon people separated from continental populations settled in Japan. Thus, the research group proposed a new "tripartite structure model" in place of the conventional "dual structure model."

Provided by Kanazawa University

Provided by Kanazawa University

Fusion of genome analysis and evolutionary anthropology

The study by a group led by Kanazawa University was a groundbreaking achievement, proposing a new theory on the ancestry of the Japanese people based on scientific evidence. However, the number of samples of genomes obtained using archeological human remains was limited, and more analysis was considered necessary. A study by the RIKEN group corroborated this tripartite-structure model based on large-scale genome information in modern Japanese.

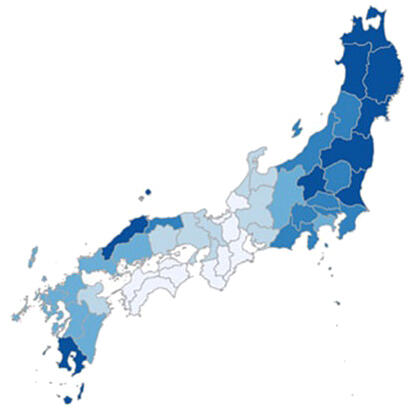

Apart from these studies, a research group led by Professor Jun Ohashi and Project Research Associate Yusuke Watanabe of the Graduate School of Science at the University of Tokyo has developed an original method to detect genetic variants derived from the Jomon people in the genome of modern Japanese. The "Jomon people admixture proportions" indicating the magnitudes of the Jomon ancestry, were estimated for different prefectures, and the results of this study were published in February 2023.

There were regional differences in the Jomon people admixture proportion. Prefectures with high proportions included Aomori, Akita, Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures in the Tohoku region, Ibaraki and Gunma prefectures in the Kanto region, and Kagoshima and Shimane prefectures, while prefectures in the Kinki and Shikoku regions had low proportions. The "ancestral admixture proportion map" does not include the Okinawa and Hokkaido Prefectures for the following reasons: Okinawa was predicted to have an unusually high Jomon people admixture proportion; and it was not possible to acquire data on the analytically important Ainu population, which is part of the Hokkaido population.

They also found that the Jomon people were genetically shorter than the migrants and had higher blood sugar and increased triglycerides levels. The Jomon people were less dependent on carbohydrates than the agricultural migrants and may have adapted to the hunting lifestyle by maintaining high blood levels of sugar and other nutrients. This was a very interesting way to look at it.

Although modern Japanese originate from the immigrants in the Yayoi period onward, the genetic elements inherited from the Jomon people characterize the Japanese among people in East Asia. This study by the University of Tokyo shows that the origins of the modern Japanese vary considerably from region to region.

Provided by the University of Tokyo

Revealing the migration and complex admixture processes of ancestral populations

The findings published by the RIKEN group this spring, as well as earlier findings by Kanazawa University and the University of Tokyo, represent the fruit of the fusion of DNA and genome analysis technology with evolutionary anthropology. We now have knowledge about not only the origins of the Japanese people but also how humans spread throughout the world based on the lineages of genetic variants found in various human populations.

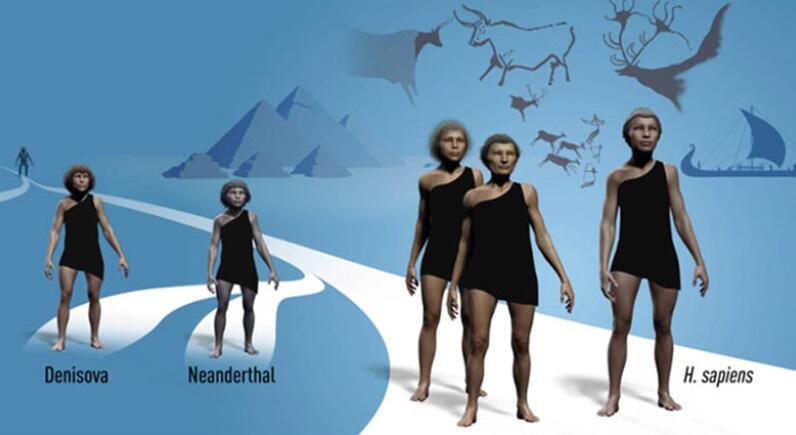

The Denisovans, who provided a new perspective on human evolution research, were named by Professor Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2022. In 2010, Pääbo published a genome sequence determined by analyzing the genome of a bone fragment from a Neanderthal man who became extinct approximately 40,000 years ago. He demonstrated that 1%−4% of the genome of modern humans living in Europe and Asia was derived from Neanderthals, providing evidence that Neanderthals crossed with modern humans.

Pääbo also determined the complete nuclear DNA sequence of a bone fragment excavated from Denisova Cave in Siberia, Russia, in 2008 and named this archaic human "Denisovan." Compared with the nuclear DNA sequences of extant humans from around the world, he also found that Southeast Asian populations inherited 4%−6% of their total DNA from the Denisovans. The Nobel Prize was awarded to him for his achievements, which have greatly advanced evolutionary anthropology.

According to Mr. Kenichi Shinoda, president of the National Museum of Nature and Science and Japan's leading expert in evolutionary anthropology and molecular anthropology, the entire sequence of human mitochondrial DNA was decoded in 1981. With the development of new methods, such as the "PCR technique" for DNA amplification, in 20 years, the entire nuclear DNA sequence of a human being was determined in 2001. With the advancement of devices, such as "next-generation sequencers," it is possible to analyze large amounts of nuclear DNA in a short time. Evolutionary anthropology has entered a new phase since 2010.

Provided by Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

Approaching the essence of humanity and the Japanese across time and space

Shinoda participated, as a key member, in the "Yaponesians Genome Project," which was conducted from 2018 to 2022 to explore how the Japanese population were established. He has produced numerous research results that revealed the scenario for the establishment of the Japanese people. Yaponesia is a word that was coined by combining Latin words to describe the Japanese archipelago.

During a monthly meeting hosted by the Japanese Association of Science and Technology Journalists (JASTJ) in January of this year, Shinohara explained the findings of this project, including "the process leading to the modern Japanese did not stop in the Yayoi period but extended to the Kofun period," and "the entire genomes of the Jomon people have been read, showing that for Japanese in Honshu, 10% of the genes (on average) are Jomon genes and 90% were introduced after the Yayoi period."

In addition, "In the Yayoi period, people with many genetic variations lived in this Japanese archipelago. We call them Yayoi people, but no one person is representative of the Yayoi people," he pointed out. We often say, "Where did the Japanese come from? I also wrote 'Where did we come from?' in the title of my book, but we should think of it as 'the establishment of the Japanese people' since we know that we came from Africa," he stated.

As it has become possible to compare DNA from samples obtained from various ages and regions, the results of such comparisons have shed light on the migration and complex admixture processes of our ancestral populations, which cannot be determined solely from differences in the shape of excavated bones. It has become clear that the formation processes and roots of the Japanese people are diverse.

"It has become possible to learn about ancient society by analyzing the genomes of ancient people. This represents the progress made in genomic research over the past decade. These scientific advances allow us to learn more about society and people." Shinoda emphasized.

DNA and genome analyses have clearly changed archeology and anthropology. The genome of the cell nucleus is packed with approximately 3.1 billion base pairs of "genetic codes." Modern technology to decipher them approaches the essence of humanity and the Japanese across time and space.

Photographed by the author

(UCHIJO Yoshitaka / Science Journalist, Kyodo News Visiting Editorial Writer)

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.