The rate of global warming in the Arctic region is three times higher than the global average. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that if the world does not implement measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, ice in the Arctic Ocean will disappear by 2050 in the worst-case scenario. Numerous observational data indicate that the amount of ice sheets on land in the Arctic is also decreasing considerably. Many meteorology experts point out that events of "extreme weather," such as heat waves, torrential rains, and droughts, which frequently occur around the world, are largely due to the meandering of westerly winds in the Northern Hemisphere caused by the warming of the Arctic region.

Research on the Arctic region is becoming even more important as damage caused by the climate change due to the warming of the atmosphere and sea surface is becoming more severe. Considerable research has been conducted by Europe and the United States, and a series of results has been published by a number of Japanese research projects. Such projects include the Arctic Challenge for Sustainability Project (ArCS II) led by the National Institute of Polar Research (NIPR), the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), and Hokkaido University.

Provided by the National Institute of Polar Research

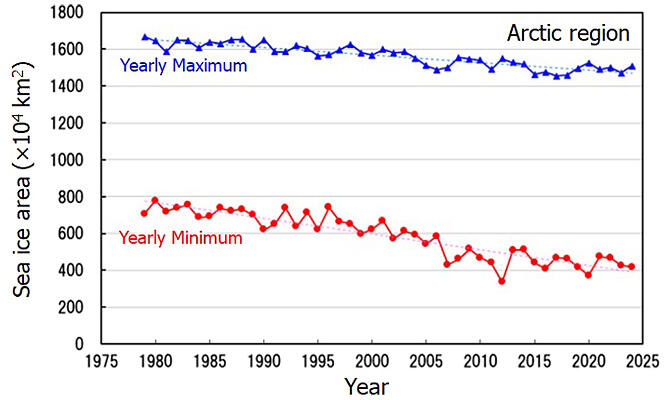

Long-term declining trend is visible.

Provided by Japan Meteorological Agency

Heat storage beneath Arctic sea ice has increased by 1.8 times in 21 years

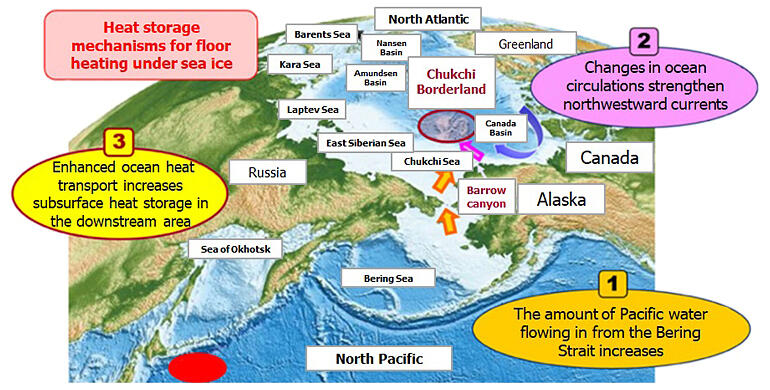

A research group from JAMSTEC, Hokkaido University, and the Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology announced at the beginning of the year that the amount of heat stored beneath sea ice in the Arctic Ocean had been increased by approximately 1.8 times in the 21 years during 1999-2020. The reasons for this increase are said to be the rising temperature of seawater flowing in from the Pacific Ocean side due to global warming as well as changes in ocean currents.

The research group comprehensively analyzed the water temperature and salinity data of the "Chukotka Borderland waters" on the Pacific side of the Arctic Ocean obtained during the 21-year-long Arctic voyages of the oceanographic research vessel "Mirai" up to the year 2020. A total of 950 sites was examined for calculating heat storage in the Chukotka Borderland waters. The results showed a notable increase in the amount of heat stored in the "submarine surface layer" at depths of 30-100 m.

This research revealed the mechanism by which the amount of heat stored under sea ice in the Arctic Ocean increases substantially as warm seawater flows in from the Pacific Ocean, increasing the amount of heat that have been originating from the Pacific Ocean, and ocean currents flowing toward the Chukotka Borderland region become stronger.

The research group believes that the stored heat acts like "floor heating" under sea ice, causing heat accumulation in the subsurface ocean over a long term, which can drastically decrease the sea ice. JAMSTEC plans to use the Arctic research vessel Mirai II, whose construction will be completed in the fall of 2026, to gain a more detailed understanding of the mechanisms behind the sea ice change. The research was supported by ArCS II and other projects, and the results have been published in the British scientific journal Scientific Reports on January 10.

Arctic sea ice has been exhibiting a long-term declining trend. The smallest sea ice area ever was recorded in 2012, and this value has not been updated since. However, the IPCC's "Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate," released in September 2019, indicates that the sea ice is likely to decrease in the future. The Japan Meteorological Agency states that the annual minimum sea ice area observed in the Arctic in 2024 was the fourth smallest since statistics began in 1979.

Provided by JAMSTEC

Provided by JAMSTEC

NIPR leads both Arctic and Antarctic research

The IPCC special report highlights that the ocean and cryosphere are important factors in predicting the future global climate change. Founded in 1973, the NIPR is a core institution that promotes the research and observation of the North and South Polar regions, including the Arctic, in addition to their well-known Antarctic observation. According to NIPR Director Yoshifumi Nogi, the institute is also working to strengthen the polar research capabilities of universities across the country through undertaking domestic and international collaborative research. International joint observations of atmosphere, snow and ice, terrestrial ecology, upper atmosphere, aurora borealis, etc. are being conducted at research and observation bases established in Greenland, Iceland, Canada, Alaska, and other countries.

Unlike Antarctica, which is shaped by a huge ice sheet, the North Pole is located on sea ice. Sea ice is thin and variable, and the region is surrounded by the Eurasian and North American continents, with human activities in some areas. The Arctic Council (AC), a group of eight nations surrounding the Arctic Ocean, including the United States, Canada, and Russia, reported in May 2021 that "the Arctic warming rate is three times higher than the global average."

NIPR has been conducting on-site observations of atmosphere, snow and ice, marine and terrestrial environments, and upper atmosphere with the ambitious goal of determining the actual state of the climate change in the Arctic region, which also impacts Japan. An example of international research involving NIPR is the International Deep Drilling Project, which is being conducted in the upper reaches of the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream (NEGIS). Ice sheets have been drilled and analyzed under this project.

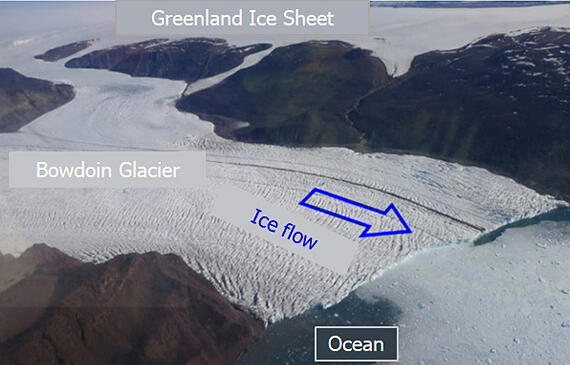

One of the project's research results is the measurement of the ice flow speed in the Greenland's glaciers over a six-year period, conducted in collaboration with Hokkaido University and others. On February 4, the researchers announced that they confirmed that the flow of the glacier toward the sea accelerates during the day when rapid ice melting occurs, during periods of high temperature, immediately after a heavy rain, and when the tide recedes and sea level drops. The results indicate that the accelerated shrinkage of glaciers occurs not only in Greenland but also in the Arctic and Antarctic regions. This shrinkage is not only due to rising temperatures but also because of acceleration in glacier flow.

In October last year, NIPR published the results of research conducted in collaboration with Nagoya University and the University of Tokyo. The results suggest that "rising temperatures in the Arctic region increase the aerosol concentration, promoting the formation of tiny ice crystals in clouds." This research will help improve accuracy in predicting changes in clouds in the Arctic region due to rapid global warming. Arctic clouds may affect the weather in the Northern Hemisphere.

Provided by NIPR

Provided by NIPR

Polar regions influence the global environment

Many meteorological researchers in Japan and abroad have emphasized that Arctic warming is a factor influencing the meandering of westerly winds. The mechanisms behind this process and extreme weather caused by the meandering of westerly winds are complex, and considerable information regarding these mechanisms remains unknown. However, numerous studies have suggested that Arctic warming reduces the temperature difference between the Arctic and mid-latitudes, affecting the speed of westerly winds and causing their flow to become more erratic.

According to Nogi, "The North Pole, together with the South Pole, balances the temperatures of the atmosphere and seawater of the entire planet, and the two poles are, so to speak, the 'Earth's cooling system.'" This means that the poles are maintaining a moderate temperature in the Earth, necessary for human survival. The environments at the North and South Poles are undergoing drastic changes due to global warming, which are having a major impact.

(October 19, 2024, at the National Institute of Polar Research in Tachikawa City, Tokyo Prefecture)

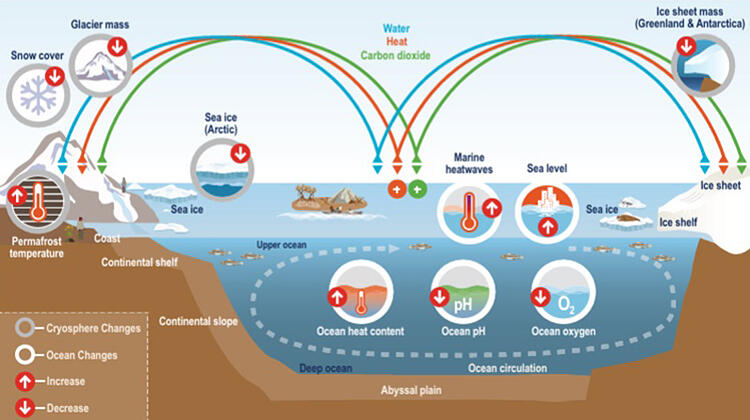

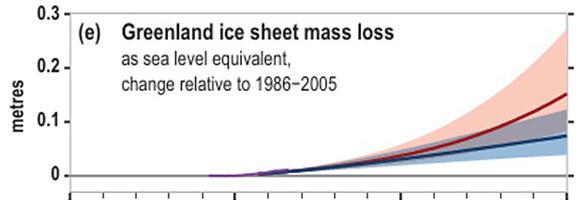

Polar ice is broadly classified into ice sheets, glaciers, and sea ice. According to NIPR, recent ice sheet loss in the Arctic region has been rapid. In particular, the mass loss of the Greenland ice sheet since the late 1900s is significant. This loss is caused by the melting of the ice sheet surface due to rising temperatures as well as collapse of glaciers into ice blocks flowing into the ocean. The number of glaciers is also predicted to decrease.

The IPCC's Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate provided specific figures. According to the report, it is highly likely that the Arctic ice sheet lost an average of more than 200 Gt (giga is 1 billion) per year between 2006 and 2015 and that the Arctic sea ice area in September decreased by 12.8% on a decade-by-decade basis between 1979 and 2018.

The IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report published in 2021 stated that the sea ice area in the Arctic region decreased by approximately 40% when comparing the average area in September over the two periods of 1979-88 and 2010-19 and that the main cause for this loss is human activities. According to the report, the annual average sea ice area in the Arctic during 2011-20 was the smallest since at least 1850.

Provided by the Ministry of the Environment

Provided by the Ministry of the Environment

Greenhouse gas reduction remains an urgent priority

The worst-case scenario presented in the IPCC's Fifth Assessment Report, which states that "Arctic sea ice will disappear by 2050," is called the "RCP8.5 scenario." It assumes that the temperature rise by the end of this century will be "around 4° (3.2°-5.4°)" compared to pre-industrial revolution levels. This is the case when countries do not take "additional measures" to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, indicating the urgent need to raise the emission reduction targets for each country.

Last December, JAMSTEC announced its research results on Antarctic sea ice, which has been noted to decrease just as much as Arctic sea ice, stating that "the impact of greenhouse gases generated via human activities has become clear." The results show that sea ice levels can increase by 2100 if "mitigation measures" are taken to reduce emissions. As the IPCC report and other reports have repeatedly pointed out, the basic measure against decreases in the sea ice and ice sheets in the Arctic region is undoubtedly a reduction in greenhouse gas emission.

Japan's current Arctic research project, ArCS II, is also positioned as an area in which the country can contribute internationally under the Fourth Basic Plan on Ocean Policy, which was approved by the Cabinet Office in April 2023. Nogi said, "Considerable information regarding drastic environmental changes in the polar regions remains unknown. We need to strengthen our research in this area in the future. It is time to specifically develop new research observations for the next project."

Provided by NIPR

(UCHIJO Yoshitaka / Science Journalist)

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.