A research team from Saitama University and other institutions has revealed that in the Venus flytrap, the carnivorous plant shaped like a bivalve shell, a protein in the cell membrane serves as a touch sensor at the base of the "sensory hairs" which detect when insects make contact. This discovery sheds light at the cellular level on part of the mechanism for sensing touch stimuli in the trap closure system, a subject that researchers including Charles Darwin, famous for On the Origin of Species and his theory of evolution, have been investigating for more than 200 years.

Provided by Professor Masatsugu Toyota of Saitama University

The Venus flytrap is a carnivorous plant native to wetlands in North America that catches insects, such as ants, by folding its leaves. Six "sensory hairs" protrude from the leaf, and touching them twice triggers the leaf to close, preventing insects from escaping.

When the sensory hairs are touched with sufficient force, they generate an electrical signal. In 2020, Assistant Professor Hiraku Suda, who studies Plant Physiology, Professor Masatsugu Toyota, who focusses on Biophysics, and their colleagues from the Graduate School of Science and Engineering at Saitama University, visualized how changes in calcium ion concentration which accompany electrical signals propagate through the leaf. They demonstrated that calcium signals may play a role similar to a "memory of touch" required for the leaf to close upon the second contact.

Provided by Toyota of Saitama University

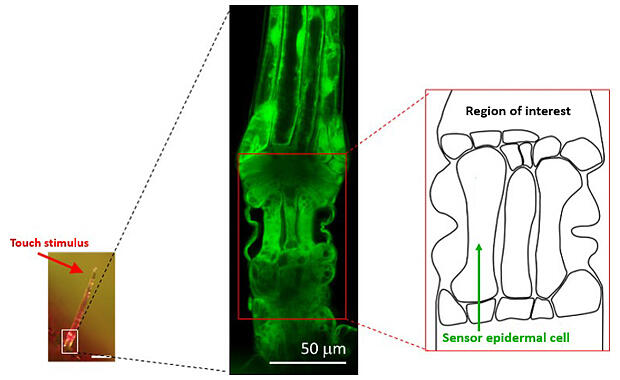

Suda and Toyota reasoned that simultaneously observing electrical and calcium signals at the cellular level would enable identification of the sensor detecting touch stimuli. They constructed a system that could measure electrical potential while using two-photon microscopy to observe sensory hairs of Venus flytraps engineered with an artificial protein that fluoresces in response to calcium ion concentration changes.

Provided by Toyota of Saitama University

When the researchers bent the sensory hairs to varying degrees while continuing observations under the microscope, strong stimuli from large deflections produced electrical and calcium signals throughout the entire leaf. In contrast, weak stimuli caused only a slight local rise in potential, and calcium signals did not propagate. They also confirmed that when cells at the bending base of the sensory hair were removed by laser ablation, calcium signals no longer spread.

Provided by Toyota of Saitama University

To identify which molecule in the sensory hairs is involved in sensing touch stimuli, the researchers focused on a protein (DmMSL10) that is abundant in Venus flytrap sensory hairs and is thought to be activated by stretching of the cell membrane to allow ions to pass from inside to outside the cell. When they examined the response to touch stimuli in Venus flytraps with this protein's gene disabled, neither electrical signals nor calcium signals were generated. In actual experiments with ants walking on the traps, the probability of catching them decreased.

Provided by Toyota of Saitama University.

"We have revealed that Venus flytraps possess a mechanism for sensing touch stimuli using genes that animals do not have," stated Suda and Toyota, adding that "this represents a major step toward elucidating plant 'senses' that differ from those of animals."

The research was conducted in collaboration with the National Institute for Basic Biology and others, with support from Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), the Strategic Basic Research Programs of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), Suntory, and others. The findings were published in the British Scientific Journal Nature Communications on September 30.

Original article was provided by the Science Portal and has been translated by Science Japan.